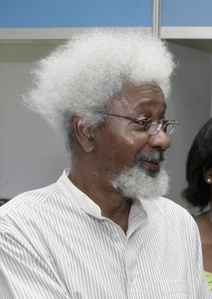

Biography

Wole Soyinka, the Nigerian born writer of international renown, is an artist proficient in multiple genres. Soyinka has written in the modes of drama (Death and the King’s Horseman and Madmen and Specialists), poetry (Idanre and other Poems), autobiography (Ake: The Years of Childhood), the novel (The Interpreters), literary and cultural criticism (Myth, Literature and the African World), and political criticism (The Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal Narrative of the Nigerian Crisis). He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986.

Soyinka not only writes for the stage but is also active in directing and producing theater. Soyinka believes that the role of performative art is very important in shaping and regenerating the culture and political identity of a people and a nation. Art connects the culture of a people with the cosmic and the archetypal primal sources of beginnings. Soyinka’s belief in the interrelation between a culture’s art and its cosmic history is manifested in his depiction of Yoruban cosmology in his writings. Due to the infusion of Yoruban deities and folklore some of Soyinka’s writing may be very distant from the average knowledge and expectations of western readership. The cultural intricacies and weight of Yoruban myth will not be explicated here, but the relation between Soyinka’s use of Yoruban myth and his ideas about the western mind and reader will be examined.

The Place of Colonial Discourse in Soyinka’s Work

In the “Author’s Note” prefacing the text of Death and the King’s Horseman, Wole Soyinka quietly inserts a very important message to potential readers of his works:

The bane of themes of this genre is that they are no sooner employed creatively than they acquire the facile tag of “clash of cultures,” a prejudicial label which, quite apart from its frequent misapplication, presupposes a potential equality in every given situation of the alien culture and the indigenous, on the soil of the latter. (In the area of misapplication, the overseas prize for illiteracy and mental conditioning undoubtedly goes to the blurb-writer for the American edition of my novel Season of Anomy who unblushingly declares that this work portrays the ‘clash between old values and new ways, between western methods and African traditions!’) It is thanks to this kind of perverse mentality that I find it necessary to caution the would-be producer of this play against a sadly familiar reductionist tendency, and to direct his vision instead to the far more difficult and risky task of eliciting the play’s threnodic essence.

Death and the King’s Horseman is a play that tells the historically accurate events of the tragic demise of Elesin, a Yoruban king’s horseman, and the moment of cosmic crisis that this brings upon his culture as a whole. As the king’s horseman it is Elesin’s role to follow his king into death through self-sacrifice. The play opens after the death of the king and thus Elesin’s death is imminent. Contrary to most western readers’ expectations, Elesin is not wracked with self-pity and rage against his fate. Elesin knows that he holds the highest honor due to his active role in continuing the Yoruban cosmos by easing the transition of their fallen leader to the realm of the dead. The moment of outward crisis comes for the Yoruba when Elesin’s self-sacrifice is stopped by the British District Officer who sees the act as a suicide that breaks civilized, legal, religious, and moral codes. What Soyinka alerts us to in the “Author’s Note” is to search for deeper human conflicts through a closer reading of the text. It was actually Elesin’s own pride and lust for the material goods of this life that caused his hesitation to commit the self-sacrifice. This moment of hesitation granted the District Officer enough time to disrupt the ritual. This story is extremely relevant to both postcolonial concepts of art and political/cultural self-projections by nations in a postcolonial situation. It contextualizes colonialism as a matter of modern history and allows art and culture to go beyond and deeper into the innate human soul to find its sources of creation. Art produced in a postcolonial situation, even within the framework of colonial difference and oppression, is not confined to finding its roots in imperial opposition. Colonialism remains a framework of a story where the “threnodic essence” inherent to humanity can be created. The colonized must not be seen as only existing in opposition to a colonial force. The self-definition of a culture can also arise out of its own cosmic history.

Soyinka and Philosophic Traditions: European and African

In Myth, Literature and the African World Soyinka discusses the intellectual history of the search for the African essence and whether the essence was destroyed for the majority of Africa during the colonial “clash of cultures.” Soyinka places himself in opposition to the search for “Africanness” by Negritude writers by proposing that the majority of Africans “never at any time had cause to question the existence of their — Negritude” (135). Soyinka identifies the basis of the misreading by the Negritude movement in their incorrect application of a supposedly universal set of western philosophical ideas to the colonial African situation:

The fundamental error was one of procedure: Negritude stayed within a pre-set system of Eurocentric intellectual analysis both of man and society and tried to re-define the African and his society in those terms. In the end, even the poetry of celebration for this supposed self-retrieval became indistinguishable from the mainstream of French poetry (136).

It must also be noted in light of this critique of western ideas that Soyinka is a student and contributor to the western philosophical and artistic traditions. Throughout his texts, Soyinka uses the work of Nietzsche, Sartre, and Fanon as well as re-writing ancient Greek drama. Soyinka creates an ingenious parable in which Descartes is written into a philosophic confrontation with an African and his famous “cogito ergo sum” is rewritten by the African:

Let us respond, very simply, as I imagine our mythical brother innocent would respond in his virginal village, pursuing his innocent sports, suddenly confronted by the figure of Descartes in his pith-helmet, engaged in the mission of piercing the jungle of the black pre-logical mentality with his intellectual canoe. As our Cartesian ghost introduces himself by scribbling on our black brother’s — naturally — tabula rasa the famous proposition, “I think, therefore I am,” we should not respond, as the Negritudinists did, with “I feel, therefore I am,” for that is to accept the arrogance of a philosophical certitude that has no foundation in the provable, one which reduces the cosmic logic of being to a functional particularism of being. I cannot imagine that our “authentic black innocent” would ever have permitted himself to be manipulated into the false position of countering one pernicious Manichaeism with another. He would sooner, I suspect, reduce our white explorer to syntactical proportions by responding: “You think, therefore you are a thinker, white-creature-in-pith-helmet-in-African-jungle-who-thinks and, finally, white-man-who-has-problems-believing-in-his-own- existence.” And I cannot believe that he would arrive at that observation solely by intuition (138-139).

Soyinka wants to dispel the idea of the “feeling intuitive African” in opposition to the “rational thinking European.” It is not a difference of reason versus emotion but a difference of world views and modes of thought. The African finds it ridiculous to compartmentalize the mind in this way. Soyinka rewrites the western obsession with the nature of the human subject as a neurotic weakness. It is immodest to reduce the existence of being to a human “particularism” of “thinking.” This passage is complemented by Soyinka’s play The Road. The character of the Professor is on a quest to find “the Word.” “The Word,” or “the Scheme,” carries both significations of Christianity’s complicity in colonialization and the Professor’s own obsession with compartmentalizing and consuming knowledge. The Professor is a delusional egomaniac who ironically resembles the ghost of Descartes from above, for the Professor evaluates the Africans on the Cartesian value of the written thought:

PROF: (speaking to SAMSON, to his mind an “authentic black innocent”): You are a strange creature my friend. You cannot read, and I presume you cannot write, but you can unriddle signs of the Scheme that baffle even me, whose whole life is devoted to the study of the enigmatic Word? (204)

The Professor is the neurotic Cartesian subject searching for the ultimate particularism of being: “the Word.” This obsession with the search for the knowledge of Death ultimately leads to the Professor’s destruction. However, opposite to the Professor is Murano, a mute. His silence is the antithesis of the verbose Professor craving the greater knowledge of being. Just as the Professor strives to carve up and consume more and more of Knowledge, Murano exists in a contentment oneness with the spiritual world. The Professor’s mastery of the Word never competes with the power Murano has through his silence. For while the Professor neurotically searches for the philosophic Word, Murano is attuned to the cosmic world through the ritual dance and evocation of the deities. Murano defies the logic of the western Word through the interconnectedness of the Yoruban cosmology of cyclic time. The unborn, the living, and the ancestral exist simultaneously and without definite boundaries. The Yoruban can access knowledge of “the Scheme” because of the cyclic transition that exists between death and life in the Yoruban cosmos unlike the western static idea of life and death. Soyinka sees the African artistic or cultural essence as never being absent or dependent upon western ideas. It has been forced into a silent existence but never denied its own being. The African cultural identity is neither anachronistic nor a philosophical import but viable in the past and present of ritual theater. (See also Myths of the Native)

Works Cited

- Soyinka, Wole. Death and the King’s Horseman. New York: Hill and Wang,1975.

- —. Myth, Literature and the African World. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- —. The Road. from Collected Plays One. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973.

Selected Works by Soyinka

Novels

- Soyinka, Wole. The Interpreters. London: Heinemann, 1965.

- —. Season of Anomy. Boston: Arena, 1973.

Memoirs

- Soyinka, Wole. Aké: The Years of Childhood. New York: Vintage, 1981.

- —. Ibadan: The Penkelemes Years. Altona: Spectrum Books, 1994.

- —. The Man Died: Prison Notes. Brighton: Africa Book Centre Ltd, 1972.

- —. You Must Set Forth At Dawn. New York: Randomhouse, 2006.

Plays

- Soyinka, Wole. Death and the King’s Horseman. New York: Hill & Wang, 1987.

- —. The Lion and the Jewel. London: Oxford University Press Ltd, 1963.

- —. Kongi’s Harvest. London: Oxford University Press Ltd, 1967.

- —. Madmen and Specialists. New York: Hill & Wang, 1987.

- —. A Play of Giants. London: Methuen, 1984.

- —. Requiem for a Futurologist. London: Rex Collings, 1985.

- —. The Road. London: Oxford University Press Ltd, 1965.

- —. The Strong Breed. London: Oxford University Press Ltd, 1963.

- —. The Swamp Dwellers. London: Oxford University Press Ltd, 1963.

Related Sites

Nobel Prize biography

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1986/soyinka-bio.html

Author: Joseph Wilson, Fall 1997

Last edited: May 2017