Background

The caste system in India is an important part of ancient Hindu tradition and dates back to 1200 BCE. The term caste was first used by Portuguese travelers who came to India in the 16th century (see Spice Trade in India). Caste comes from the Spanish and Portuguese word “casta” which means “race”, “breed”, or “lineage,” but many Indians use the term “jati”. There are 3,000 castes and 25,000 sub-castes in India, each related to a specific occupation. These different castes fall under four basic varnas:

Brahmins – priests

Kshatryas – warriors

Vaishyas – traders

Shudras – laborers

Caste not only dictates one’s occupation, but dietary habits and interaction with members of other castes as well. Members of a high caste enjoy more wealth and opportunities while members of a low caste perform menial jobs. Outside of the caste system are the untouchables. Untouchable jobs, such as toilet cleaning and garbage removal, require them to be in contact with bodily fluids. They are therefore considered polluted and not to be touched. The importance of purity in the body and food is found in early Sanskrit literature. Untouchables have separate entrances to homes and must drink from separate wells. They are considered to be in a permanent state of impurity. Untouchables were named “Harijans” (children of god) by Gandhi. He tried to raise their status with symbolic gestures such as befriending and eating with untouchables. Upward mobility is very rare in the caste system. Most people remain in one caste their entire life and marry within their caste (see Christianity in India, Jews in India).

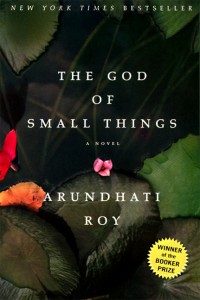

The Novel

In Arundhati Roy’s novel, The God of Small Things, the laws of India’s caste system are broken by the characters of Ammu and Velutha, an untouchable or Paravan. Velutha works at the Paradise Pickles and Preserves Factory owned by Ammu’s family. Yet, because he is an untouchable, the other workers resent him and he is paid less money for his work. Velutha’s presence is unsettling to many who believe he acts above his station. His own father notes this problem: “Perhaps it was just a lack of hesitation. An unwarranted assurance. In the way he walked. The way he held his head. The quiet way he offered suggestions without being asked. Or the quiet way in which he disregarded suggestions without appearing to rebel” (73).

Hindus believe that being an untouchable is punishment for having been bad in a former life. By being good and obedient, an untouchable can obtain a higher rebirth. Velutha’s lack of complacency causes him many problems throughout the novel. “It was not entirely his fault that he lived in a society where a man’s death could be more profitable than his life had ever been” (267). Although he is a dedicated member of the Marxist Party, his Untouchable status makes other party members dislike him, and so local Party leader Comrade K.N.M. Pillai would be more politically successful without him.

When Velutha has an affair with Ammu, he breaks an ancient taboo and incurs the wrath of Ammu’s family and the Kerala police. He breaks the rigid social rules of the caste system and therefore, the authorities must punish him. Roy describes the policemen’s violent actions as being done out of fear, “…civilization’s fear of nature, men’s fear of women, power’s fear of powerlessness”(292). The division between the Touchables and Untouchables is so ingrained in Kerala society that Velutha is seen as a nonhuman: If they hurt Velutha more than they intended to, it was only because any kinship, and connection between themselves and him, any implication that if nothing else, at least biologically he was a fellow creature – had been severed long ago (293).

Traditionally, a woman who has had sex with a man from a lower caste would be expelled from her caste. The reason such scandal is caused by the affair of an untouchable and a touchable woman might be difficult for some American readers to grasp. Reviewer Patrick Sullivan claims that “an excellent parallel would be a wealthy Southern white woman falling in love with a black man” (Sullivan).

Caste in India Today

Although The God of Small Things takes place in 1969, the caste system is still present in India, especially in rural areas. Today there are about 250 million Untouchables. Caste discrimination has been against the law since 1950, but prejudice continues. The United Nations estimates that there are 115 million child laborers and 300 million starving people in India, most of which are untouchables. Government programs and quotas have tried to raise the living standards of untouchables by reserving places in the legislature, government jobs, and schools. These government actions often result in an increase of violence by caste members. Urbanization, economic development, and industrialization benefit untouchables by breaking down caste barriers. In the cities of India, members of different castes are constantly in close contact and forced to interact with one another which helps to weaken the strict rules of the caste system.

Untouchables have also become a strong and organized political force who refer to themselves as Dalits. In a recent interview with Emily Guntheinz, Arundhati Roy was asked to comment on the caste system. Her reply follows: “It’s the defining consideration in all Indian politics, in all Indian marriages… The lines are blurring. India exists in several centuries simultaneously. So there are those of us like me, or people that I know for instance, to whom it means nothing… It’s a very strange situation where there’s sort of a gap between… sometimes it’s urban and rural, but it’s really a time warp” (n. pag.).

Works Cited

- Avishai, Margalit. “Decent Equality and Freedom: A Postscript.” Social Research 64.1 (Spr. 1997): 147.

- Kala, Awind. “Your Caste is Your Life.” Scholastic Update (Teacher’s Edition) 129.13 (11 Apr. 1997): 5.

- McGirk, Jan. “Raped or Revered?” Marie Claire Oct.1997: 43-48.

- Roy, Arundhati. The God of Small Things. New York: Random, 1997.

- Zubrzycki, John. “Lower Castes Still stuck on India’s Bottom Rung.” The Christian Science Monitor 89.193 (29 Aug. 1997): 1.

Author: Allison Elliott, Fall 1997

Last edited: October 2017

4 Comments

Thanks for sharing this topic.

Can you plz tell me the names of few more books which represent class and caste conflict ?

Other than Mulk Raj Anand untouchables .

A very sophisticated book on the caste system in India, one that anthropologists use all the time, is Louis Dumont’s Homo Hierarchicus. It is not an easy read. If you know anything about structuralism, Dumont is a structuralist so keep that in mind. An old book but one that documents village life in India, is by another anthropologist, McKim Marriott. It is called Village India. If you’re a college student both of these should be in your library even if you’re in India.

It is important to take note of the influence of British colonialism on the shape the caste system took and the shape it has today. See for example http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-48619734