A wealth of languages make their home on the Indian Subcontinent. Estimates for the number of languages spoken range from over three hundred to well over a thousand, though the bulk of these are dialects of one language or another. Even with the most conservative estimates, these languages differ greatly in their technical aspects, but a Russian linguist, G.A. Zograf, assigns four major language families to the Subcontinent: Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, Austro-Asiatic, and Tibeto-Burman. Most languages come under one of the first two categories which, together, account for nearly 75% of the various idioms of the Subcontinent (Ethnologue). In his book, The Languages of South Asia, Zograf provides detailed descriptions of many of the sub-categories of languages in this part of the world. This website considers only the two broadest categories: the Indo-Aryan and Dravidian language families. It should also be noted that the history of the Indus Valley and its civilizations is currently a hotly debated issue. In no way is this site meant to favor one theory of migration and/or conquest over another; rather, its purpose is simply to shed some light on some important differences between the major Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages in the context of India, specifically.

A wealth of languages make their home on the Indian Subcontinent. Estimates for the number of languages spoken range from over three hundred to well over a thousand, though the bulk of these are dialects of one language or another. Even with the most conservative estimates, these languages differ greatly in their technical aspects, but a Russian linguist, G.A. Zograf, assigns four major language families to the Subcontinent: Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, Austro-Asiatic, and Tibeto-Burman. Most languages come under one of the first two categories which, together, account for nearly 75% of the various idioms of the Subcontinent (Ethnologue). In his book, The Languages of South Asia, Zograf provides detailed descriptions of many of the sub-categories of languages in this part of the world. This website considers only the two broadest categories: the Indo-Aryan and Dravidian language families. It should also be noted that the history of the Indus Valley and its civilizations is currently a hotly debated issue. In no way is this site meant to favor one theory of migration and/or conquest over another; rather, its purpose is simply to shed some light on some important differences between the major Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages in the context of India, specifically.

Indo-Aryan

The Indo-Aryan (IA) family of languages dates back to the first millennium B.C., when epic Sanskrit comes onto the world stage. Classical Sanskrit follows this and provides a highly standardized language preserved in grammatical works, the most famous being “Paniniís” of the fourth century BC. Zograf categorizes these, as well as the Vedic language, as Old IA. As time progressed, phonology and grammar changed to yield another linguistic dynasty, Middle IA. Here, the major languages come under the name “Prakrits” and survive in the early writings of Buddhism, Jainism, and the injunctions of the Emperor Ashoka. The latest phase of development gives rise to today’s languages, which fall under the category of New IA. According to Zograf, these began development at the end of the first millennium AD (Zograf 10-16).

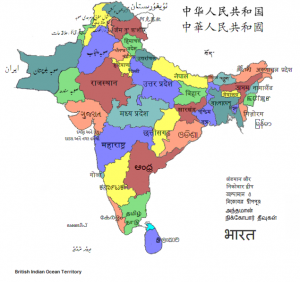

Though concentrated in the northern part of India, New IA encompasses many of the most widely spoken languages in India, as well as their respective dialects. Some of these include; Hindi, Panjabi, Sindhi, Rajasthani, Gujarati, Marathi, Bihari, Bengali, and Kashmiri.

In regards to the vocabulary of these languages, Zograf notes a heavy influence of Sanskrit on the vocabularies of New IA languages. However, the amount of borrowing from Sanskrit varies from one language to another as does the borrowing from other forms. These other forms fall into two major categories, the first being Arab/Iranianisms. Iranian and Turkish invaders changed not only the social and political make-up of the region, but its languages, as well. The words that arrived directly from the troops, however, do not hold the importance of literary Persian, which came into Indian languages from the Muslim upper class. Finally, with Muslim entry into the region, Arabic enters the lexicon, most notably of Urdu, from the religion of the conquerors. A different breed of conquerors, those in search of economic gains, also marked the languages of India. Minor additions come from the Portuguese, Dutch, and French, but, as one might expect, the bulk of Europeanisms come from the British. Despite half a century of independence and numerous efforts to rid the nation of them, Anglicisms still pervade India’s lexicons (Zograf 17-20). Borrowing from either Arabic and Persian sources — such as Hindi/Urdu (H/U) “kitab” for “book” — or European sources can occur for many reasons, among them, filling a gap in the vocabulary when the Indian language had no equivalent term or marking the prestige of the speaker.

The Dravidian Language Family

In the efforts to replace English words and phrases with Indian ones, reformers looked mainly to Sanskrit, though India is home to another ancient language family, the Dravidian, which exists almost exclusively in southern India, though pockets of Dravidian languages survive in the Northern parts of India and western Pakistan. Little research exists on the origins of Dravidian speech, though researchers know with some degree of certainty that few, if any connections exist between Dravidian and other language families in India or isolated languages outside the nation. Luckily, central and northern India have isolated areas of Dravidian speech that preserve the traits of the ancient language that today’s major Dravidian languages–Tamil, Telegu, Malayalam, and Kanada–do not (Zograf 129-130).

Interestingly, today’s Dravidian languages do bear some resemblance to New IA ones. Zograf mentions this briefly, but University of Stanford professor Murray Emeneau discusses the subject of similarities between the two families in his book, Language and Linguistic Area. Zograf, however concentrates on the differences between the two families and brings to light a number of interesting points. In direct contrast with New IA, Dravidian speech contrasts long and short vowels. Words in this family typically end in a vowel and stress the first syllable. In addition to these observations, Zograf notes two specifically Dravidian sounds, a retro-flex fricative “l,” and an alveolar-rolled “r” (131). In other words, Dravidian languages differ significantly from IA ones even at the level of the actual sounds in the language, to say nothing of how words or sentences are formed.

These exclusive traits complement a vocabulary saturated with unmodified Dravidian words. This does not mean to imply that these languages are immune to linguistic mingling. On the contrary, Sanskrit and the Prakrits present themselves in each of the major Dravidian tongues, though Tamil remains largely immune to the addition of IA words. Telegu and Malayalam are the two languages most influenced by IA, though vast differences in pronunciation — as the Dravidian sound system makes the borrowed words conform to its rules — make these loan words somewhat invisible. In addition to these new words, Europeanisms can be heard in the major Dravidian languages. Similarly, the Dravidian speech pockets in north and central India draw from the surrounding sea of IA conversation.

The differences between IA and Dravidian idioms include sophisticated linguistic analyses that, though ignored on this site, are presented in great detail in other works, such as those cited herein.

Orthography/Writing Systems

Although there is archaeological evidence of written language in India from the third millennium B.C.E., Brahmi, the orthographic ancestor of most modern Indian scripts, appears in the third century B.C.E. as one of the vehicles for the edicts of Ashoka. (The other — Kharoshthi — seems to have died out by the fifth century C.E.). Brahmi developed into the Devanagari character system and spread with Sanskrit throughout India to influence or form the basis of most of the major languages’ orthographies, IA or Dravidian. (see a diagram of their relations; also see Comrie, et al.).

Along with Islam came the Qu’ran and Arabic script that Urdu speakers have adopted. Although closely related enough to Hindi to consider the two languages “ethnolects” (i.e. dialects spoken by different religious communities) of a broader Hindustani, many speakers will resist that classification. At very least, literacy in Urdu’s Arabic script and Hindi’s contemporary Devanagari mean very different things.

Finally, European mercantilism and imperialism brought the roman script to India, and, in addition to European languages — notably English– that use it, some presses or publications will transliterate Indian languages into roman script for practical reasons.

Language, Literature, and Culture

As a part of a site dedicated to postcolonial issues, it is important to note here that linguistic differences have social, cultural, and political consequences too numerous to summarize easily. The sub-continent’s diversity makes defining a national language or literature virtually impossible. With so many traditions, and their complex weave of borrowings and translations, selecting texts and finding the resources to study them will provide more material than institutions in India or abroad can handle. Coupled with that problem is that the prestige of writers working in English or Hindi and older Sanskrit texts tends to overshadow other traditions like Urdu and Bengali, not to mention the Dravidian languages, to people in the West. In short, despite the recent interest in Indian literature, there is still a lot more to be done.

Works Cited

- Breton, Roland J-L.. Atlas of the Ethnic Communities of South Asia. Walnut Creek: Alta Mira Press, 1997.

- Comrie, Bernard, Stephen Matthews, and Maria Polinsky, eds. The Atlas of Languages: The Origin and Development of Languages Throughout the World. New York: Facts on File, Inc. 1996.

- Emeneau, Murray B. Language and Linguistic Area. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1980.

- Grimes, Barbara F. ed. “Ethnologue.” 1996. Summer Institute of Linguistics, Inc. Web. 27 Mar 1998.

- Zograf, Georgi A. Languages of South Asia. Trans. G.L. Campbell. Boston: Routledge, Keegan & Paul, 1982.

- “Evolution of Indian scripts.” Colorado State University. Web. 27 Mar 1998.

Works to Consult

- Baumgardner, Robert Jackson. South Asian English : structure, use, and users. Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 1996.

- Bright, William. Language variation in South Asia. New York : Oxford University Press 1999.

- Ratihi, Ali R. Language vitality in South Asia. edited by Ali R. Fatihi. International Conference on South Asian Languages and Linguistics (8th : 2008 : Aligarh Muslim University) A. R Fatihi; Aligarh Muslim University. Dept. of Linguistics.Aligarh : Dept. of Linguistics, Aligarh Muslim University, 2009.

- Kachru, Braj B, Yamuna Kachru and S.N. Sridhar. Language in South Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Kothari, Rita. Chutnefying English : the phenomenon of Hinglish. New York : Penguin Books, 2011.

Author: Veda Khulpateea, Spring 1998.

Last Updated: August 2017

1 Comment

Right your that linguistic differences have social,

cultural, and political consequences too numerous to summarize easily.