I who am poisoned with the blood of both

Where shall I turn, divided to the vein?

I who have cursed

The drunken officer of British rule, how choose

Between this Africa and the British tongue I love?

“A Far Cry from Africa”

Introduction

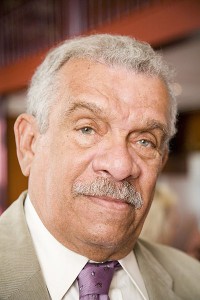

When the Swedish Academy awarded poet and playwright Derek Walcott the Nobel Prize in 1992, it recognized what many commentators on Caribbean literature had long celebrated, a brilliant artist’s response to the what the Academy called the “complexity of his own situation.” Walcott’s life and work inhabit a teeming intersection of cultural forces, a space that his friend and fellow-poet James Dickey described with a remarkable litany: “Here he is, a twentieth-century man, living in the West Indies and in Boston, poised between the blue sea and its real fish…and the rockets and warheads, between a lapsed colonial culture and the industrial North, between Africa and the West, between slavery and intellectualism, between the native Caribbean tongue and the English learned from books, between the black and white of his own body, between the sound of the home ocean and the lure of European culture (8).” (See also Mimicry, Ambivalence and Hybridity) These relationships have remained a major subject of his work because his imagination has never lost contact with his native West Indies, which animates his writing with its intense physical beauty. His writing explores the troubled relationship between this gift and a colonial heritage and the problems of a fragmented postcolonial identity.

Early Life and Poetry

Walcott was born in 1930 on the island of St. Lucia, the child of a civil servant and a schoolteacher and the descendant of two white grandfathers and two black grandmothers. Though his first language was a French-English patois, he received an English education, an apprenticeship in language that his mother supported by reciting English poetry at home and by exposing her children to the European classics at an early age. In “What the Twilight Says,” an autobiographical essay published in 1970, Walcott writes of the two worlds that informed his childhood: “Colonials, we began with this malarial enervation: that nothing could ever be built among these rotting shacks, barefooted backyards and moulting shingles; that being poor, we already had the theater of our lives. In that simple schizophrenic boyhood one could lead two lives: the interior life of poetry, and the outward life of action and dialect (4).” (See also Frantz Fanon)

Walcott’s art arises from this schizophrenic situation, from a struggle between two cultural heritages which he has harnessed to create a unique creolized style. His early poetry booklets, published in the late 1940s with money borrowed from his mother, reveal a self-conscious apprentice determined to make what Walcott called verse “legitimately prolonging the mighty line of Marlow and Milton (31).” English and American critics often have been ambivalent about his use of the Western literary tradition and Walcott has also drawn criticism from Caribbean commentators, who accuse him of neglecting native forms in favor of techniques derived his colonial oppressors (See Colonial Education). To be sure, his early works seem overpowered by the voices of English poetry, and his entire oeuvre respects the traditional concerns of poetic form. But if his poetry demonstrates a significant relation to tradition, it also manifests an elegant blending of sources — European and American, Caribbean and Latino, classical and contemporary. Later works, including In a Green Night: Poems 1948-1960, reveal a poet who has learned his craft from the European tradition, but who remains mindful of West Indian landscapes and experiences. The task of Walcott as a young poet, one he undertook with an enthusiasm for both imitation and experimentation, was to develop an idiom adequate to his subject matter. Walcott passed away on 17 March 2017 (see Chamoiseau’s dedication).

Early Dramatic Writings

Though his poetry displays a passion to record Caribbean life, this tendency is more apparent in Walcott’s drama, which draws consistently not only on his native patois, but also on regional folk traditions. In the 1950s, after taking a degree from the University College of the West Indies, Walcott wrote a series of verse plays, including Henri Christophe which recounts an episode in Caribbean history using the diction and plotting of Jacobean tragedy. His subsequent forays into dramatic writing, The Sea at Dauphin and Ione, mingle the influences of J. M. Synge and Greek drama with a new emphasis on West Indian language and customs. During this period Walcott also taught and wrote as a journalist in Grenada, before moving to Trinidad, where he gathered a group of actors and founded the Trinidad Theatre Workshop. While in Trinidad, Walcott developed a mature dramatic idiom in plays such as Ti-Jean and his Brothers and Dream on Monkey Mountain, which put an elevated dialect in mouths of common West Indian folk. In “What the Twilight Says,” Walcott describes his desire to fill these plays with “a language that went beyond mimicry, . . . one which finally settled on its own mode of inflection, and which begins to create an oral culture, of chants, jokes, folk-songs, and fables (17).” Chronicling a peasant fantasy of rejecting the white world and reclaiming an African heritage, Dream on Monkey Mountain not only makes effective use of native dialect, but also satirizes the bureaucratic idiom of colonialism. Language becomes a route to racial identity and a necessary resource for the survival of West Indian communities.

Mature Writings

While Walcott dedicated much of the 1960s to developing the Trinidad Theatre Workshop and to rewriting earlier dramas, his primary focus was on poetry. Between 1964 and 1973 he published four volumes which continued his exploration and expansion of traditional forms and which increasingly concerned themselves with the position of the poet in the postcolonial world. In contrast to the plays of this period which arise from a sense of shared colonial history and local mythology, The Castaway and Other Poems (1964) draws on the figure of Robinson Crusoe to suggest the isolation of the artist. “As a West Indian,” Katie Jones suggests, “the poet can be seen as a castaway from both his ancestral cultures, African and European, stemming from both, belonging to neither. To salve this split, Walcott creates a castaway who is also a new Adam . . . whose task is to name his world. Walcott’s castaway is a poet who creates and gives meaning to nothingness” (Brown 38). Coping with internal division remains a concern in The Gulf, which calls on the body of water separating St. Lucia from the United State as a metaphor for the breach between the poet and all he loves, between his adult consciousness and childhood memories, his international interests and the feeling of community in his homeland. Walcott explores these themes again in Another Life, a book-length autobiographical poem that examines the important roles of poetry, memory, and historical consciousness in bridging the distances within the postcolonial psyche.

This investigation transferred to his dramatic writings in the 1970s, which address the problems of Caribbean identity against the backdrop of political and racial strife and which increasingly find solutions to these troubles in the individual. These works also display an expansion of his artistic concerns into different genres. After a comical turn in Jourmard, Walcott wrote two musicals in collaboration with Galt MacDermont: The Joker of Seville (1974), a patois adaptation of Molina’s El buladorde Sevella, and O Babylon! (1976), a portrayal of Rastafarians in Jamaica at the time of Haile Selassie’s 1966 visit and which uses reggae music as a means of exploring West Indian identity. O Babylon! also marked the end of Walcott’s association with the Trinidad Theatre Workshop and the beginning of new period of dramatic writing, highlighted by plays such as Remembrance (1977) and Pantomime (1978). The protagonist of Remembrance, Albert Perez Jordan, is a schoolmaster who lost his oldest son in the 1970 Black Power uprising and who remains distressed by a political commitment he cannot understand. Unable to connect with his family or with his own past, Jordan finds himself divided between an older generation committed to tradition and a younger one playing at revolution. Characters in the comedic Pantomine confront similar divisions, but here the issue of race comes to the fore. Reviving the Crusoe story once again, Walcott creates a play-within-a-play and recasts the roles so that Jackson, a black hotel servant, plays Crusoe and his white employer plays Friday. This reversal highlights the fraught relationship that binds black to white, master to slave, and colonizer to colonized. Far from being an irreparable situation, however, Jackson’s ability to synthesize his calypso talents with a poetic use of the English language suggests a respect for differences and a possibility for healing old wounds.

Life and Work in the United States

If his drama has examined the role of music and language in mending divisions, Walcott’s poetry has sought to do the same through a continuing examination of the relation of life to art (see Hybridity and Postcolonial Music). After his break with the Trinidad Theatre workshop in 1976, Walcott directed his attention increasingly to the United States, where he has held a number of teaching positions, including a long-standing appointment at Boston University. It is not surprising then that much of the poetry written during this period reflects the tensions between his role as an educator at a mainland institution and as a poet from a small island nation. But even before Walcott began spending most of the year away from the West Indies, his experience as a transient international poet, one called to read and lecture around the world, had supplied his poetry with images of painful departures and the guilty homecomings. In the title poem of Sea Grapes, for instance, Odysseus is portrayed as a divided man, who finds himself both a husband going home and an adulterer unable to forget his trespasses.

Rather than avoid such painful dilemmas, Walcott’s works from the 1980s explore the “bitter sweet pleasures of exile” experienced when one has become estranged from his beloved homeland, when one has become divided between “North” and “South” (the subdivisions of The Fortunate Traveller) and between “Hear and Elsewhere” (The Arkansas Testament). While these works deal with general themes such as injustice, racism, hatred, oppression, and isolation, they continually return to inner divisions of an exile and increasingly to the role of art in mending these divisions. Midsummer is important in this regard because its lyrics record a year in the life of the poet as he returns to the Caribbean from the United States in search of childhood memories and as he travels throughout region recording its sense of community from the perspective of an outsider. Despite his feelings of loss and his increasing awareness of cruelty in the world, the poet finds not only the strength to endure but also some reassurance in artistic vision, in the English and patois languages he loves and in masterpieces of modern art.

Nobel Prize and Omeros

[pl_raw] [pl_video type=”youtube” id=”pSH4qjN2v_c”] [/pl_raw] While Walcott has been praised for his lasting contributions to Caribbean theater, receiving credit for establishing a truly native dramatic form, the Nobel committee singled out a work of poetry when it selected him as laureate in 1992. Omeros (modern Greek for Homer) is a book-length poem that places his beloved West Indies in the role of the ancient bard’s Cyclades. This retelling of the Odyssey is not inhabited by gods and heroic warriors, but by simple Caribbean fishermen, whose Greek names register their hybrid identities. And though it is composed in terza rima, Omeros is not an epic in any traditional sense. Rather than describing a single quest, the shape-shifting narrator, who appears in Homeric guise at several points in the poem, recounts a number of journeys into the hidden corners of colonial history. The success of Omeros validates the substance of Walcott’s entire oeuvre, for here are the themes that have consistently preoccupied the poet: the beauty of his island home, the burden of a colonial legacy, the fragmentation of Caribbean identity, and the role of the poet in addressing these concerns.Since winning the Nobel Prize, Walcott has continued to write prolifically, producing a new epic poem, The Bounty in 1992 and three more collection of poems, including White Egrets which won the T.S. Eliot prize in 2011. In these works, he continues to explore the complex legacy of colonialism with a poetic vision that recognizes the range of traditions comprising his beloved West Indies, and with a poetic voice that harmonizes the discord between the English canon and his native dialect.

Walcott in His Own Words

on his poetic language:

It was no problem for me to feel that since I was writing in English, I was in tune with the growth of the language. I was a contemporary of anyone writing in English anywhere in the world. What is more important, however — and I’m still working on this — was to find a voice that was not inflected by influences. One didn’t develop an English accent in speech; one kept as close as possible to an inflection that was West Indian. The aim was that a West Indian or an Englishman could read a single poem, each with this own accent, without either one feeling that is was written in dialect.

Conversations 53

on his status as a Caribbean writer:

I am primarily, absolutely a Caribbean writer. The English language is nobody’s special property. It is the property of the imagination: it is the property to the language itself. I have never felt inhibited in trying to write as well as the greatest English poets. Now that has led to a lot of provincial criticism: the Caribbean critic may say, “You’re trying to be English,” and the English critic may say, “Welcome to the club.” These are two provincial statements at either end of the spectrum.

Conversations 55

on his reception as a Caribbean writer:

So if you ask me about how I feel if I’m reviewed, I think I’ve had a parallel equivalent, politically I have been through, in my life, an identical series of phases which would be that of being a colonial, being someone given adult suffrage, being someone given self-government, and being someone who becomes very public so that the decades of my life maybe the equivalent of the political decades of the Caribbean. Now, on the other had, those decades or those definitions have sometimes been bestowed by the empire; in other words, the empire has said, okay, you are no longer a colonial, you can now have adult suffrage; you no longer have adult suffrage, you can now be independent; you are no longer independent, you can now be a republic.

Conversations 55

on America, colonialism, and identity:

The whole idea of America, and the whole idea of every thing on this side of the world, barring the Native American Indian, is imported; we’re all imported, black, Spanish. When one says one is American, that’s the experience of being American — that transference of whatever color, or name, or place. The difficult part is the realization that one is part of the whole idea of colonization. Because the easiest thing about colonialism is to refer to history in terms of guilt or punishment or revenge, or whatever. Whereas the rare thing is the resolution of being where one is and doing something positive about that reality.

Conversations 54

Selected Works by Derek Walcott

Poetry

- Walcott, Derek. Another Life. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1973.

- —. The Arkansas Testament. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1987.

- —. The Bounty. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1997.

- —. The Castaway, and Other Poems. London: Cape, 1965.

- —. Epitaph for the Young. Bridgetown: Barbados Advocate, 1949.

- —. The Fortunate Traveller. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1981.

- —. The Gulf, and Other Poems. London: Cape, 1969.

- —. Midsummer. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1984.

- —. Omeros. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1990.

- —. The Prodigal. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2004.

- —. Sea Grapes. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1976.

- —. Selected Poems. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2007.

- —. The Star-Apple Kingdom. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1979.

- —. Tiepolo’s Hound. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2000.

- —. White Egrets. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2010.

Drama

- Walcott, Derek. A Branch of the Blue Nile. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1986.

- —. The Capeman. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1997.

- —. The Charlatan. Kingston: Trinidad Extra Mural Department, University College of the West Indies, 1954.

- —. Ione: A Play with Music. Kingston: Trinidad Extra Mural Department, University College of the West Indies, 1957.

- —. Drums and Colors: An Epic Drama. Kingston: Trinidad Extra Mural Department, University College of the West Indies, 1958.

- —. Dream on Monkey Mountain. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1967.

- —. Henri Christophe: A Chronicle in Seven Scenes, 1950

- —. In a Fine Life. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1970.

- —. The Joker of Seville. London: Cape, 1973.

- —. O Babylon! New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1976.

- —. Odyssey: A Stage Version. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1993.

- —. Steel. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1991.

- —. Walker and the Ghost-Dance. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2002.

Works Consulted

- Atlas, James. “Constructing Modern Idiom on a Base of Tradition.” The New York Times. (9 Oct. 1992): 30.

- Brodsky, Joseph. “On Derek Walcott.” The New York Review of Books. (10 Nov. 1983): 39-41.

- Brown, Stewart, ed. The Art of Derek Walcott. Chester Springs: Dufour, 1991.

- Dickey, James. “Worlds of a Cosmic Castaway.” The New York Review of Books. (2 Feb. 1986): 2.

- Gale Research. “Derek Walcott.” Contemporary Literary Criticism Select. 1998. Web.

- Lyndersay, Mark. “Photography of Derek Walcott.” Lyndersay Photographs Page. 10 April 2000. Web. <http://www.wow.net/macmark/html/Walcot17.html>

- McWatt, Mark A. “Derek Walcott: An Island Poet and his Sea.” Third World Quarterly 10.4 (Oct. 1988): 1607-1615.

- Terada, Rei. Derek Walcott’s Poetry: American Mimicry. Boston: Northeastern UP, 1992.

- Walcott, Derek. “What the Twilight Says: An Overture.” Dream on Monkey Mountain. New York: Farrar, 1970. 3-40.

- Walcott, Derek. Conversations with Derek Walcott. Ed. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 1996.

Related Sites

Nobel Prize biography

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1992/walcott-bio.html

See also Paul Gilroy: The Black Atlantic

Author: Patrick Bixby, Spring 2000

Last edited: May 2017

2 Comments

The above writing about Derek Walcott is taken from a certain book. What is the name of the book? Please reply it to me as soon as possible.

Hi Moumita,

The sources consulted for the content are listed at the end of the page, under “Works Consulted.”