It is so hard to collect my thoughts after watching the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, especially when I realize that the whole experience of knowing the director, understanding its important position in cinematic history, putting it on my “watch list” for 5 five years (I first marked the film in 2019), and finally seeing it last night at a big screen.

I would not have finished watching it at home if it had not been shown in a cinema. This mindset explains why I was reluctant to pick 2001 to watch on a movie night or with friends, which further explains my shrinking attention span and growing flippancy and impetuosity towards longer, harder, and more sophisticated content. I am curious to learn, for those folks who watch the film for the first time, would you voluntarily choose to watch it again? If bearing the awareness of how great it is to the cinema – in terms of special effects, sound design, and narrative structure – or to the epistemology on subjects like human evolution, early civilization, the fascination with outer space, and machines gaining autonomy, would you do it again just to understand more about this profound work?

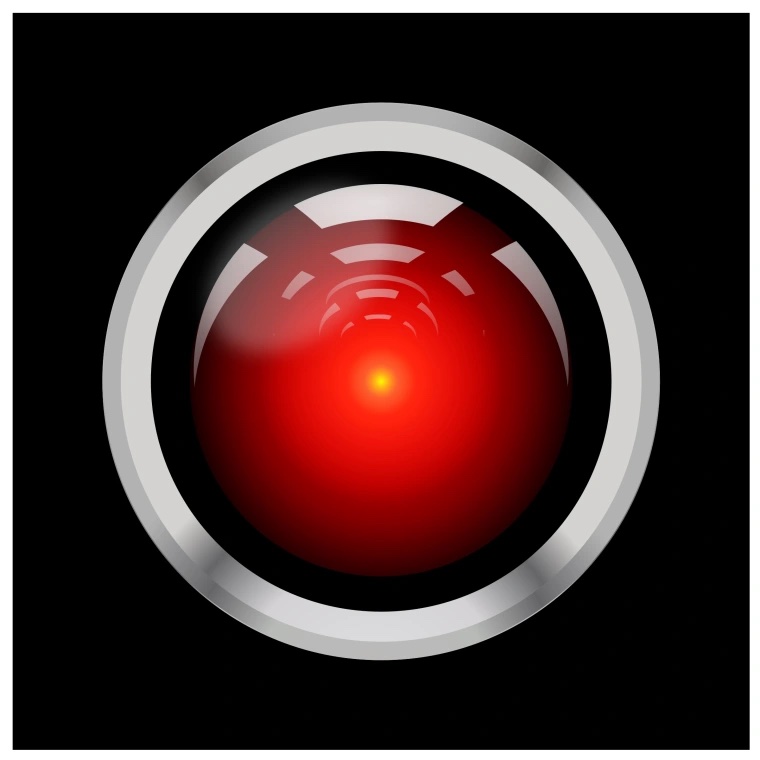

Setting aside from the grand narrative and subjects intended to provoke, Kubrick makes use of two techniques to create such an immersive yet confusing cinematic experience. First, he used the contraction of time. Second, he used distinct points of view. The three stages of the film, or what other people may call “evolution”, were granted with completely different and inconsistent time intervals. When there were only mammals on earth, they had a clear cut of how time elapsed from sunrise to sunset, from waning to the waxing of the moon, from discovering the tools to utilize the tools. The world back then runs in its simple and undisruptive form. We as viewers are like an omniscient god watching its pulsation. Then the first time contraction happened in that classic match cut of the bone and the spaceship, advancing thousands of years to which humans became the most intelligent entities in history and seemingly had the power of controlling everything. Similar to Kubrick and Arthur Clarke’s imagination for the 21st century back in 1968, humans kept extravagant exploitation of resources or tools to facilitate their endless exploration of unknown space. Such continuity was broken after HAL’s introduction and when we suddenly see HAL’s point of view. Viewers’ god-like overlook upon a small chapter of history is dramatically taken by Kubrick in replacement of a repressive, creepy, and catchy fisheye lens, forcing us to be at that scene and engage with the Jupiter Mission. Later, such time-traveling and shifted perspectives take in form of surrealistic montage. For instance, juxtaposing the bizarre and motley experience of shooting through an interstellar tunnel with Dave’s section-like fixed frame tells us about the time and velocity while keeping the explanation at bay.

Walking out of White Hall, I feel like having a dream. It feels separated while captivating. To some extent I no longer care about its ethical allusion and universal value since it is hard to frame it using a scholarly approach without analyzing how the film is made, and what techniques it fashioned. So in repones to my question: whenever I would love to have an unusual dream, I know which film can be the possible intake.

Leave a Reply