We have discussed so much about artificial intelligence this semester. We have discussed advanced technology in films, novels those films are adapted from, AI’s application in real life, its advantages, and damage it has on humanity.

One thing that does not seem to get mentioned a lot whether on internet or in our class is the philosophical analysis of AI. For me, it is conflicted, because it is hard to connect – philosophy and AI – when one is highly theoretical and the other requires too much real-life practice.

However, AI is not a simple technology, but a complicated one that challenges our understanding of consciousness, free will, and the essence of humanity, which are topics frequently discussed by philosophers. Therefore, it is important to see AI through the lens of philosophy.

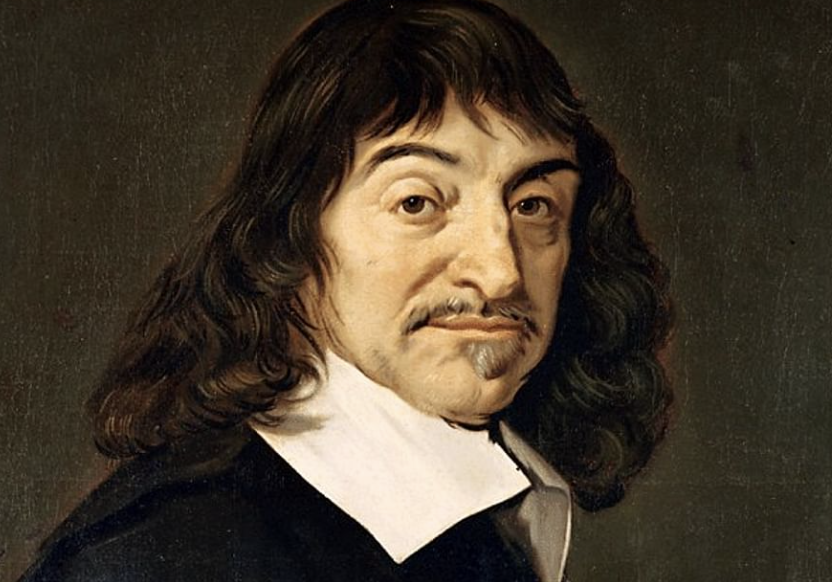

René Descartes is a good match.

René Descartes : French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician. Often been called the father of modern philosophy. Philosophical ideas including Cartesian doubt, cogitation (thought), mind-body dualism, etc.

Descartes has a method of doubt. The most famous saying by him is the one involving cogito, “I think, therefore I am.” We can doubt a lot of things, but we cannot doubt that we think, because doubting itself is a form of thinking, and it is also impossible to doubt one’s own existence, because it is the “I”, that is doubting.

How does his ideas relate to AI? Here are two articles that address this topic briefly:

https://www.thecollector.com/philosophy-of-artificial-intelligence-descartes-turing

While reading these, another interesting concept that relates to Turing test caught my eye, so I want to post that as well: The Chinese Room Theory (https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/chinese-room/):

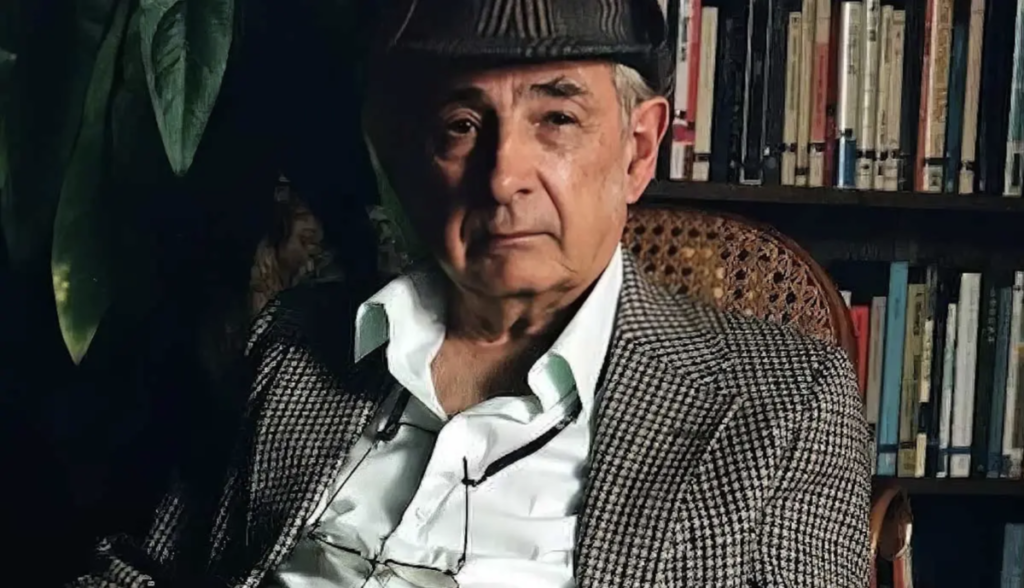

Concept by American philosopher John Searle to demonstrate that a mind or consciousness for computer could not be realized.

“Searle imagines himself alone in a room following a computer program for responding to Chinese characters slipped under the door. Searle understands nothing of Chinese, and yet, by following the program for manipulating symbols and numerals just as a computer does, he sends appropriate strings of Chinese characters back out under the door, and this leads those outside to mistakenly suppose there is a Chinese speaker in the room.

The narrow conclusion of the argument is that programming a digital computer may make it appear to understand language but could not produce real understanding. Hence the “Turing Test” is inadequate. Searle argues that the thought experiment underscores the fact that computers merely use syntactic rules to manipulate symbol strings, but have no understanding of meaning or semantics. The broader conclusion of the argument is that the theory that human minds are computer-like computational or information processing systems is refuted. Instead minds must result from biological processes; computers can at best simulate these biological processes. ”

A page on Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_room) also explains Searle’s understanding of what he called “Strong AI” (The appropriately programmed computer with the right inputs and outputs would thereby have a mind in exactly the same sense human beings have minds), under the title “Strong AI as computationalism or functionalism”.

Leave a Reply