Andrew Bujalski’s 2013 picture, Computer Chess, chooses to take a highly non-stereotypical route to examining the tech boom of the 1980s by not focusing on the sexy tech giants born in this period in the likes of Microsoft, Apple, or IBM and their respective techno-cultural icons of Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, but rather the steps towards wider processing systems which make computers what they are today. While the film undoubtedly takes more than the proper steps to recreate the atmosphere of early 80’s computer culture, any glance at the computers necessary hardware for solely the chess game, like MIT’s Sargon, or the hairstyles and clothing choices of the coding teams themselves, gives beyond adequate construction of an atmosphere. However, what Bujalski presents in his 2013 flick gives a very interesting perspective when the type of filmmaking that is being used, particularly its form, here being black and white analog, may give further distinction upon whose perspective the film is from.

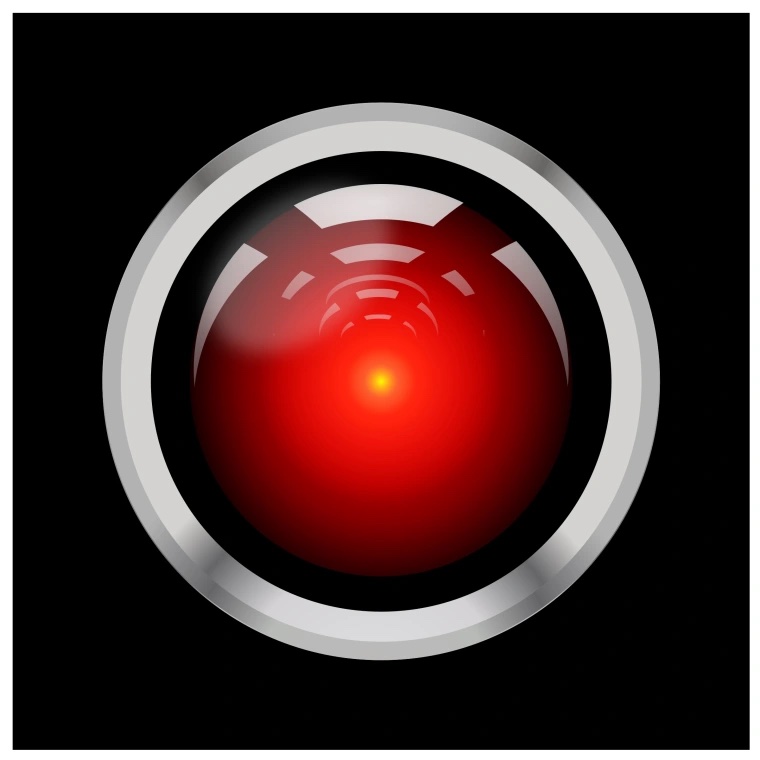

While the choice of recording on old-fashioned black and white analog makes the viewer of the film even deeper into the era of the script’s setting, the title cards in the classical font which is found on each programming script for the computer chess players themselves from each respective university or organization. While the film already presents itself as holding a level of ambiguity, particularly in the character’s reactions to one another’s moves and words alike, the narrative in tandem leads to a overarching mysterious question. What presents itself as the most mysterious and ambiguous question are those regarding the consciousness that each computer system could possibly posses. The first instance of this can be seen, arguably, in the bar conversation near the end of the picture between Pat Henderson and Peter Bishton. Here, Henderson not only admits American Central Intelligence interest, Pentagon advisors, in the programming itself, the most unsettling moment comes when he questions his chess computer’s ability to hold a soul. Upon proposing this question Henderson not only is questioned by the computer with the same exact phrase, but the computer projects a ultrasound when it is forced to respond to the question, “who are you?” What takes this question home in the film’s narrative is its conclusion between a disappearing hotel hooker and a rival coder, Michael Papageorge, where upon commencing any copulation, the mystery woman turned sex partner, reveals herself as an AI system.

This narrative about the consciousness of computers is undoubtedly deeply concerning, but it is the analog presentation of the film, particularly the title cards that give further distinction. While the script of the title cards have already been defined as having the same font as the script in the computers, when the possibility of the computers being sentient is put into action, the choice of analog and title cards present a different situation. While the movie itself surrounds the human characters in the film, the presentation of these human characters seems to not be from a human perspective. Perhaps the choices of aspect ratio and analog are to give the audience the computers’ perspective rather than the humans’. Fundamentally, this idea of humanity loosing control of its machines, described as a ‘preservationist plea’ by columnist Ann Hornaday, comes not only from the narrative. It is Bujalski’s presentation of the film itself, the title font, camera placement, and black and white analog, that makes the audience sit in the shoes of a conscious computer in this film’s world, and arguably in our own.

Hornaday, Ann. “Computer Chess’ honors archaic computers, in form and content.” The Washington Post. 8th August, 2013.

Leave a Reply