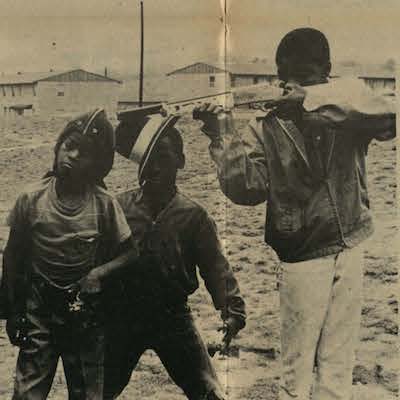

Less than a year after its 1971 opening, East Lake Meadows had become known as “little Vietnam.”

And by the time the project was being redeveloped in the 1990s, as Adam Goldstein discusses in his article, reports in the Washington Post, New York Times, and the Atlanta Journal Constitution could refer to East Lake Meadows by this moniker without any need for an explanation about the name’s meaning or origin. In the public’s imagination the two had become synonymous, and both symbolized all of the problems that had come to beset public housing: violence, crime, drugs, poor maintenance, and police indifference. However, the exact origins of the nickname “little Vietnam” have been lost over time and apocryphal stories have often filled the void.Poor construction at East Lake Meadows led to increased maintenance costs and meant that shortly after opening, the housing project and landscape were in disrepair.

The sheer numbers of residents and ratio of adults to children meant East Lake Meadows was ripe for problems, especially considering the complex lacked support facilities such as a day care center, health clinic, welfare office, recreation space, and community center when it first opened. Due to these deficiencies, Reverend Phillips Barnhart, the pastor of the East Lake United Methodist Church and an advocate for tenants’ rights, had even sought a court injunction in October 1970 against the housing project’s opening. As he predicted: “you just don’t put that many people in that small a space without having chaos.” 1

Chaos did ensue at East Lake Meadows almost immediately after residents moved in to the housing project. Some of the biggest problems were drugs and violence. Rumors circulated that pushers sold drugs out of ice cream trucks and guns were ubiquitous amongst residents of all ages. Police were reportedly slow to respond and when they did, they were reportedly indifferent and the residents were uncooperative. Moreover, because the project was in Atlanta but part of DeKalb County, DeKalb police did not patrol the area, while Atlanta police were hesitant to make arrests. In response to these issues, residents and advocates attended a meeting of the Atlanta aldermanic Police Committee in December 1971. It was at that meeting that Vietnam was invoked for the first time to describe East Lake Meadows. An exchange took place between Alderman Jack Summers and the Reverend Barnhart, who had spoken presciently about East Lake Meadow’s looming troubles: 2

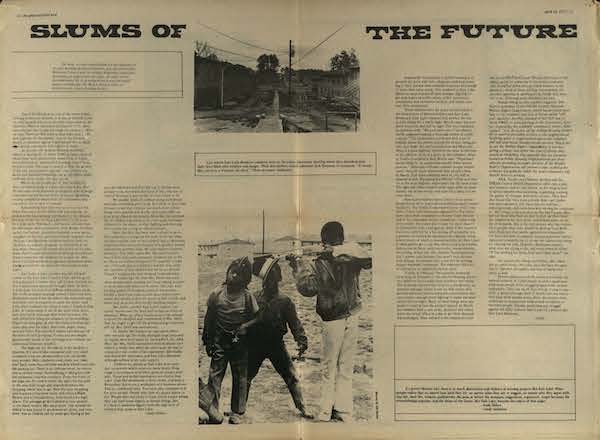

Journalist Bill Seldon reported on this conversation between the two men in a January 1972 Atlanta Constitution front-page article – the first in a four-part series on East Lake Meadows and the problems it faced. Vietnam and East Lake Meadows were now indelibly connected in print.

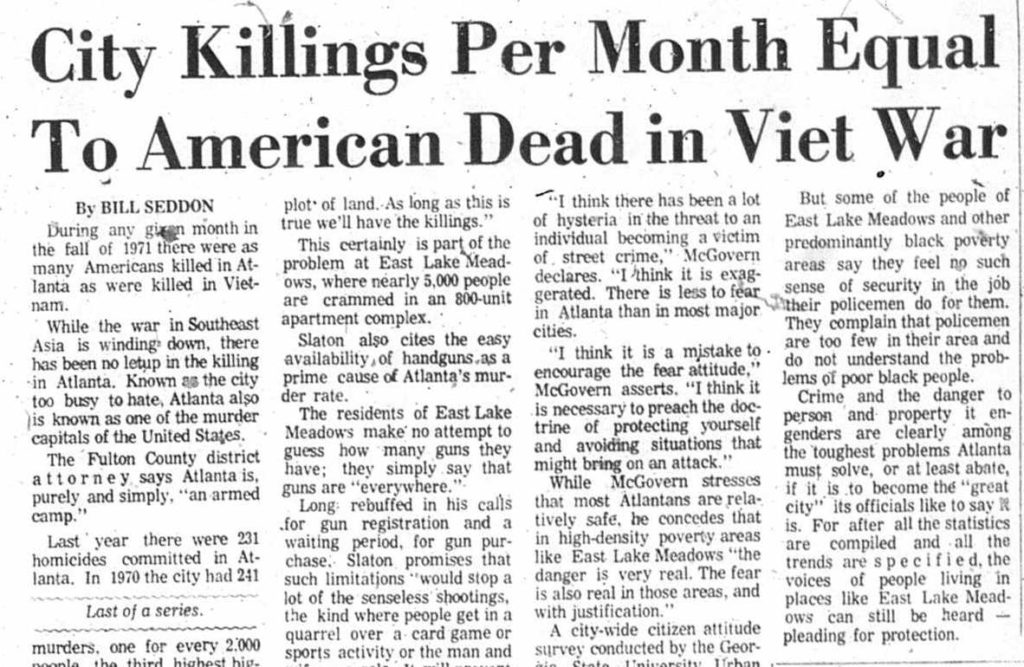

Seldon further solidified the connection between East Lake and Vietnam two days later when he wrote: “During any given month in the fall of 1971 there were as many Americans killed in Atlanta as were killed in Vietnam. While the war in Southeast Asia is winding down, there has been no letup in the killing in Atlanta.” 3 Seldon not only continued to join East Lake Meadows and Vietnam in the minds of the public, but he made it sound as if public housing was actually worse. The name conjured up images of the danger and violence associated with a war-torn country. From that point forward, “little Vietnam” became shorthand not only for the housing project but also for the conditions at East Lake Meadows. By the early 1970s, many viewed the war in Vietnam as unwinnable and associating it with East Lake Meadows imbued the public with the idea that perhaps the housing project was also unsalvageable.

War rhetoric used in relationship to Atlanta’s public housing was not new in the 1970s. When the housing program began in the 1930s, public housing promoters often invoked tropes of war and battle when they talked about the slum clearance that would take place to make way for new public housing projects. In the early years of the Atlanta Housing Authority, the idea that war was being declared on the slums was a powerful concept that the people of Atlanta were willing to stand behind. As a patriotic fervor struck the United States in the midst of and after World War II, the idea of war was noble and patriotic. In that context, defeating the slums meant defeating an enemy and liberating the people who had been held captive by bad living conditions. 4 However, by the 1970s war had taken on a different meaning both in the United States and in relationship to Atlanta’s public housing projects. Now, war was being waged against public housing, and the very thing that had once been seen as the liberator was now seen as the enemy. If a war against the conditions in East Lake Meadows were, indeed, unwinnable, and had been thought about that way almost as long as the housing project had existed, then the public could support demolition of the housing project. Moreover, if the war against “Little Vietnam” was viewed as just as unwinnable as the real war in Vietnam had been, then perhaps its demolition can be understood as a case of winning a battle in what was overall an unwinnable war. But while a dangerous location was removed from Atlanta’s landscape, the people who once resided in the housing project have not necessarily been liberated. Redevelopment in Atlanta has become a new war against the poor who were removed from their former homes and were ineligible for residence in the new developments that have replaced public housing across the city.

Citation: Schank, Katie Marages. “What’s in a Name? East Lake Meadows and Little Vietnam.” Atlanta Studies. March 16, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20170316.

Notes

- Bill Seldon, “Poor Services Plague Area,” Atlanta Constitution, January 18, 1972, 11A.[↩]

- Bill Seldon, “Residents Say Help Is Slow to Arrive,” Atlanta Constitution, January 17, 1972, 1A. The Great Speckled Bird also published a version of Summer’s comment. See Candy, “The Slums of the Future,” Great Speckled Bird, April 24, 1972, 12-13.[↩]

- Bill Seddon, “City Killings Per Month Equal to American Dead in Viet War,” Atlanta Constitution, January 20, 1972, 10A. Emphasis in the original.[↩]

- The force behind Techwood Homes, Atlanta’s first public housing project, and also the first chairman of the Atlanta Housing Authority’s Board of Directors, Charles Palmer relied heavily on images of war and battle. He gave speeches titled “World War Against the Slums” and also titled his autobiography Adventures of a Slum Fighter.[↩]