Age Differences in Rates of Forgetting by Children and Adults: Explaining Childhood Amnesia

One way we learn about autobiographical memory and its development is by using cue words to prompt children and adults to recall past events. We ask participants to “think of a specific memory involving ice cream,” for example. We also ask them to tell us how old they were at the time of the event. By giving several cue words and plotting how long ago the events happened, we can see the distribution of memories across the lifespan.

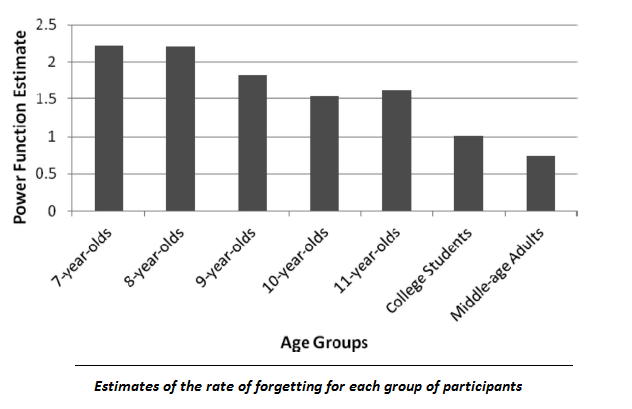

We have used this technique to uncover important similarities—and also critical differences—in the distribution of autobiographical memories produced by children and adults. Both children and adults readily generate memories in response to the cues, and for both groups, some of the memories are from long ago. Yet examination of the ages of the memories makes clear one important difference between children and adults—even as old as 11 years of age, children exhibit a faster rate of forgetting than adults (in the figure below, the higher the bar, the faster the rate of forgetting).

The results provide a ready explanation for infantile or childhood amnesia (the relative paucity of memories from the first years of life among adults). It suggests that we experience amnesia for childhood events because in childhood, we forget autobiographical experiences at a rapid rate. This means that over time, there are fewer and fewer events that can be remembered. You can read more in Bauer & Larkina (2014).

The “Fates” of Autobiographical Memories over Time

Another way we study the development of the ability to recall personally meaningful events is by asking participants to tell us what they remember about the past. We then examine the descriptions that they provide in terms of how complete and detailed they are. In a 4-year longitudinal study, we used this method to track developmental changes in autobiographical narratives and also study the “fates” of memories across development.

The study included 4-, 6-, and 8-year-old children as well as adults who shared personal memories with us once a year for four years. We are using this rich data base to catalog the many ways memory changes over development and when autobiographical memory becomes adult-like. We have already found out that both the number of details and level of complexity in narratives increase across childhood. In addition, we have found relations between children’s memory for life events and their general cognitive abilities, such as speed of processing, source memory, and memory for temporal order.

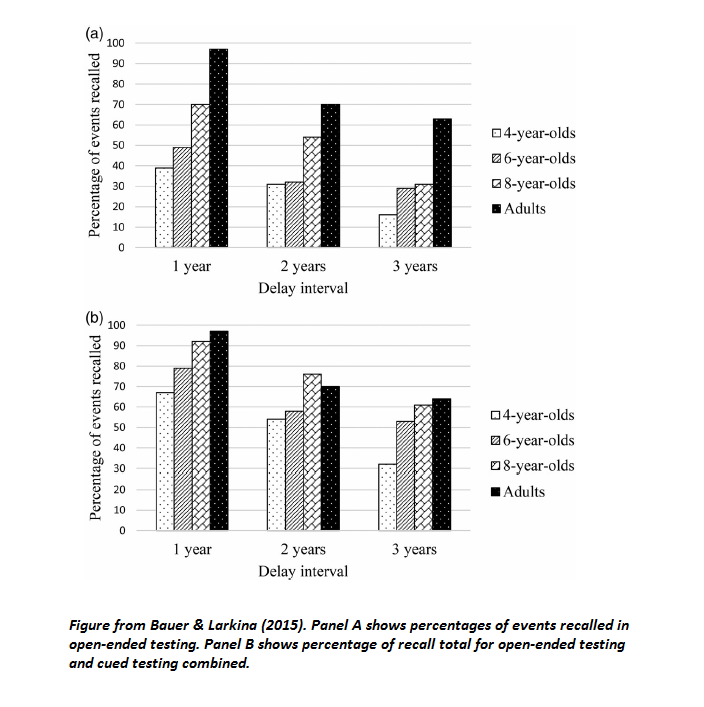

In terms of the “fates” of memories, the graph below shows the percentages of events recalled after delay intervals of 1, 2, and 3 years, for 4-, 6-, and 8-year-old children and adults. What is clear from the top graph is that adults remembered many more events than all of the child groups, and especially the 4-year-olds. But notice what happened when we provided the participants with additional cues about their memories—in the bottom graph, with the aid of additional reminders, the “gap” between children’s and adults’ memories became smaller.

We are currently using our data to track the fates of memories over the course of the study, allowing us to identify factors that predict their survivability and also individual differences in the development of these memories. You can read more about some of these findings in Bauer & Larkina (2015).

Putting the “Auto” in Autobiographical Memory

One of the differences between autobiographical memories and memories of grocery lists and where we parked our car is that autobiographical memories are about ourselves—they are personal and self-defining. An important question in autobiographical memory research is when in development memories take on this personal or autobiographical quality. Is it there even in our earliest memories of childhood, or does it develop only later, as we develop our own personal identity? To find out, we used a web-based survey asking adolescents and young adults to provide memories from different periods of their lives, from ages 1 to 5 years, all the way to the most recent year.

We found that for both adolescents and young adults, even the earliest memories had a personal quality and were rated as highly meaningful and significant. In fact, even though there was an almost 10 year age difference in our two groups of participants, they described and rated their memories in very similar ways. This tells us that even our earliest recollections have an “auto” or self quality to them. You can read more about our findings in Bauer, Hättenschwiler, & Larkina (2016).