How do Children and Adults Expand their Knowledge?

One of the major tasks of development is to build a knowledge base. This requires that we sort through the vast amount of information that we inevitably experience each day and organize it. We also continually add new information over time. The semantic memory system plays an integral role in the abstraction and storage of knowledge. Semantic memory also exhibits a capacity for extending itself such that new information can be self-generated through processes such as integration—the combination of two or more separate, but related traces of information to yield new knowledge.

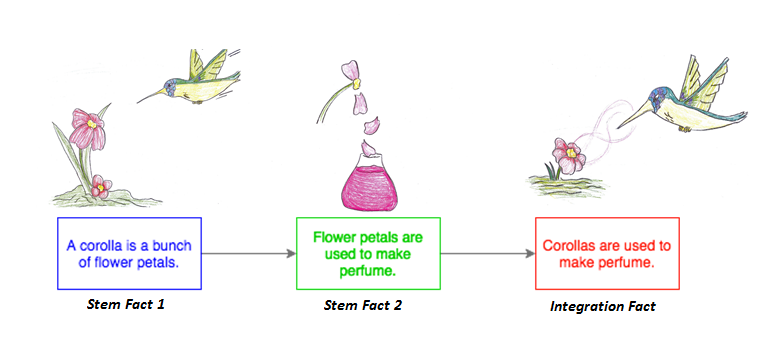

Our ability to function on a daily basis and to navigate the world is so inherently dependent on the process of extending knowledge—and the process is so efficient—that we pretty much take it for granted. In the Memory at Emory Lab, we are “unpacking” the process so that we can understand it, and how it changes with development. To do this, we examine how children and adults combine newly learned facts and generate novel, integrated understandings. An example of how we seek to assess this process of integration in children is shown below.

In this task, children are presented with two facts, each in a story: “A corolla is a bunch of flower petals,” and “Flower petals are used to make perfume.” Children then are asked a question that they can answer by integrating the two facts. For example, they may be asked, “What are corollas used to make?” A response of “perfume” would indicate that the child had successfully integrated the two facts and, as a result, generated a novel piece of information.

Age-related Developments in Integration and Self-generation

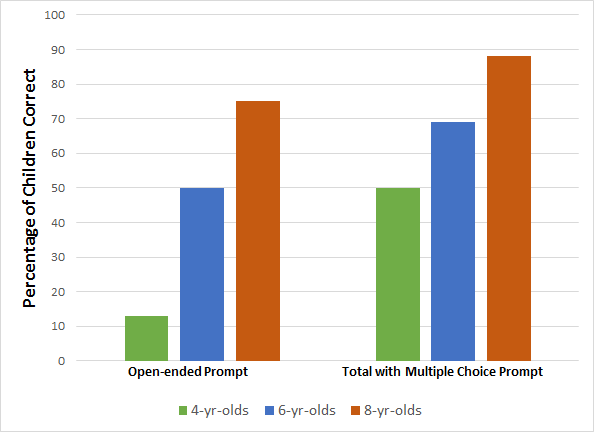

We have studied the process of integration of separate episodes and extension beyond them to create new knowledge across the preschool and into the early school years. As illustrated in the figure below, there are developmental differences across this period, such that by the time children are 8 years old, they readily volunteer that “perfume” is what corollas are used to make. In contrast, children only 4 years of age require more support to generate new knowledge. When simply asked the question “What are corollas used to make?” they do not very often generate the answer. However, when they are given the opportunity to select the correct answer in multiple-choice format, they demonstrate their ability to extend their knowledge through integration. In other studies, we have found that children are more likely to generate new knowledge if we give them the “hint” that they could use the stories we just read to help them answer the question. They also do better when the main character in the stories is the same (such as the hummingbird) versus when different characters are featured in each story. These findings tell us something about the “boundary conditions” of self-generation of new knowledge and thus shed light on the cognitive processes involved. You can read about these findings in Bauer & Larkina, 2016.

New Knowledge is Remembered over Time

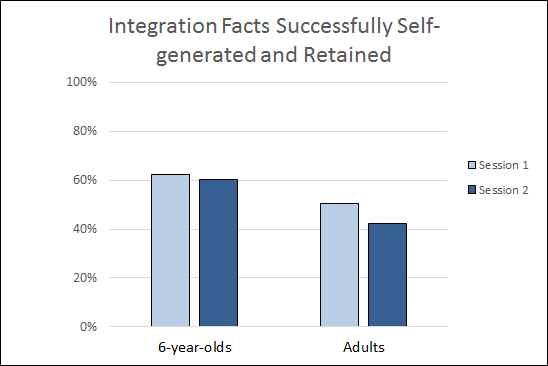

For self-generation of new knowledge to be truly meaningful, the new information must persist over time. In several studies, we have tested whether information that children and adults self-generate at Session 1 is still remembered by them 1 week later. We have found impressive levels of retention of new information over this period of time, for both children and adults. As indicated in the figure below, 6-year-olds self-generate new knowledge on 63% of trials. They remember 60% of the new information 1 week later. To test college students, we do not use stories, but instead, we have them read long lists of novel facts. Based on the facts, college students self-generate new knowledge on 50% of trials. They remember 42% of the new information 1 week later. Studies such as these make clear the potential for newly self-generated knowledge to be incorporated into the knowledge base. This demonstrates the psychological and potentially, the educational, relevance of the process. You can read about these findings in Varga & Bauer (2013) and Varga, Stewart, & Bauer (2016).

New Knowledge is Rapidly Incorporated into the Knowledge Base

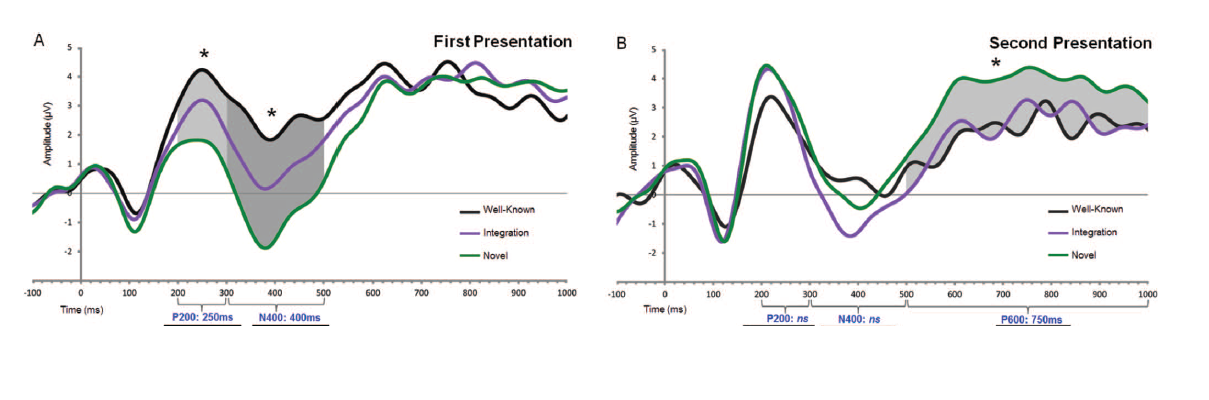

One of the reasons we might take extension of knowledge for granted is that it happens very quickly—so quickly that we are not even aware of it. We have used event-related potentials (ERPs; described in “Imaging memory and emotion with ERP”) to measure just how rapidly this process unfolds. We asked college students to read long lists of facts, some of which could be integrated with one another to self-generate new knowledge. We then recorded ERPs as they listened to more facts, some of which were entirely (Novel), some of which were familiar (Well-known: “Emory University is located in Atlanta”), and others of which were facts that could have been self-generated through integration (Integration Facts). As shown in the left panel below (see shaded areas), upon the first 400ms presentation of the facts, participants’ brains responded to the Integration Facts as if they were intermediate between Novel and Well-known. Upon the second presentation (right panel of the figure, shaded area), the Integration Facts were no longer intermediate but instead, were treated as Well-known. These findings indicate the rapid transition of newly self-generated knowledge from “novel” to “well known.” This is a revealing window into the process by which a knowledge base is constructed. You can read more about this study in Bauer & Jackson, 2015.

Learning across Two Languages

Developing a knowledge base involves remembering information and adding new information that is learned under different circumstances—such as at a different time, from a different person, or from different materials. Dual-language education is an education model that provides content instruction through two different languages. This model of education has excellent academic outcomes as well as the benefit of learning a second language. Also, this model of education is increasing across Georgia and at a national level. We are interested in how children build a knowledge base when instruction is through multiple languages.

This past year, we visited two dual-language schools. Locally, we worked with children learning Spanish, French, and Mandarin at the GLOBE Academy. In addition, we traveled to North Carolina to work with a group of children in a Spanish/English program. We also had several children from the surrounding area come to the Child Study Center and listen to stories in English, Spanish, or in one of each language. Between stories, children completed vocabulary measures in English and Spanish. We are excited to investigate how children are able to put together facts and information that is related from across different languages.

The findings from this line of work have implications for informing the development of representational capacities and, thereby, basic cognition. Furthermore, this research has the potential to inform education by shedding light on ways in which this learning mechanism may be promoted in classroom settings and learning situations more generally.