These projects are concerned with community-building and resistance in Black rural areas. Angel’s project looks at Afro-Colombians on the country’s pacific coast and their forms of resistance in the face of legal and extralegal negligence and exploitation. Ola’s looks at the influence of Octavia Butler’s Parables series of books on Black agrarians and abolitionists, specifically through the Earthseed Land Collective (ELC), a land co-op in Durham, North Carolina.

Ola

These are a few sources I have used to gain insight on ELC’s work.

Anderson, W. C., & Samudzi, Z. (2018). As black as resistance: Finding the conditions for liberation. AK Press.

This is a book of Black anarchist theory. A solid portion of it describes the importance of communal land stewardship (in cooperation with Indigenous communities) to Black liberation. While abolitionism is not the same as anarchism, there is a great bit of overlap between the two as movements and ideologies. One member of ELC told me that, while they prefer not to use a Eurocentric term like “anarchism,” the group’s politics are essentially anarchist. Similar arguments have been made about Butler’s politics, as many of her works appear to portray anarchist societies as superior alternatives to the world we know.

brown, a. m. (2017). Emergent strategy. AK Press.

adrienne maree brown is currently the most famous Octavia Butler scholar. brown is an activist facilitator who takes inspiration from Butler in their mobilization of “emergent strategy,” an approach to activism that places special attention on critical connections, critical mass, and relationality with the environment. They advocate for individual, communal, and planetary change in very spiritual ways, in accordance with the tenets of Earthseed. brown’s work has had a lot of influence on members of ELC and their surrounding community.

brown, a. m. (2020). We will not cancel us: Breaking the cycle of harm. AK Press.

Part of brown’s “Emergent Strategy” series, here they write specifically about the role of emergence and spirituality in abolitionist spaces and transformative justice. They point out that abolitionist activists and spaces are too often lacking in patience and forgiveness. They emphasize a community’s spiritual need to practice accountability beyond punishment. I find it helpful in imagining how agrarian communities can find alternatives to policing.

Butler, O. E. (2001). On racism. NPR. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5245679

An article written by Octavia Butler expressing some of her thoughts on racism and its role in her work. As stated in this article, Butler believes that to rid oneself or the world around them of racism means to resist the hierarchical thinking that is seen as natural to human societies. This line of thinking lends itself to more horizontal organizations of society, as demonstrated in the Parables books. Abolitionists are actively in the process of dismantling hierarchies, although many do not explicitly understand it as such. Taking a cue from Butler and Earthseed practitioners, we can see that abolitionist spaces can exist outside of governance and pecking orders, provided we can resist our hierarchical tendencies.

Butler, O. E. (2016). Parable of the sower (Seven Stories Press edition). Seven Stories Press.

The book that introduced Earthseed as a concept. It tells the story of Lauren Oya Olamina, a young Black woman who escapes her destroyed neighborhood in the midst of ecological disaster and political turmoil. She starts her own religion, Earthseed, around the idea that God is change itself and we must work in community to shape it. We get to see Earthseed used as a way of coping with loss, building community, and sustaining hope.

Butler, O. E. (2017). Parable of the talents (Seven Stories Press edition). Seven Stories Press.

In my opinion the better half of the Parables duology, this story gives us a better look at intentional Earthseed communities, their structure, and their practices. Lauren starts a spiritual environmentalist town on reappropriated land. Everything is communally oriented, from education, to farmwork, to entertainment. They actively try to help those around them and liberate them from modern slavery. Earthseed as a political theology is also framed in direct opposition to conservative Christianity and the carceral state.

Davis, A. Y., & Dent, G. (2022, October 20). Visualizing abolition with Angela Y. Davis and Gina Dent, October 20, 2020.

A presentation by Angela Davis and Gina Dent, co-authors of Abolition. Feminism. Now. They talk about the importance of aesthetics and collective imagination in abolitionist activism. According to them, movement spaces need art to imagine, communicate, and mobilize around social justice problems and solutions. I see this in the effect Octavia Butler has had on Black agrarians, helping them imagine and embody more liberatory spaces.

Frazier, C. M. Black feminist ecological thought: A manifesto. (2020, October 1). Atmos. https://atmos.earth/black-feminist-ecological-thought-essay/

In this article, Frazier explains the connections and parallels between Black Feminist Thought and ecocriticism. Ecocriticism is the study of the relationship between literature, art, and the environment, and the field has historically excluded Black people. Black women are among those most affected by ecological disaster, and are often those at the forefront of environmental activism. Frazier states that Black feminisms, ecocriticism, and environmental activism can and should have a mutually beneficial relationship, and I believe Butler’s work demonstrates this well.

Gumbs, A. P. (2018). M archive: After the end of the world. Duke University Press.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs was a founding member of the Earthseed Land Collective. This book is a collection of “poetic artifacts” within a framing narrative in which a post-apocalyptic researcher discovers the history of capitalism and anti-Blackness. It critically examines imposed distinctions between art, science, politics, etc. It is a solid example not only of Octavia Butler’s legacy, but of the role art takes in helping us analyze our world and envision alternatives.

Imagining abolition (episode 3): The abolitionist pod. (2021, September 10). Black Lives Matter. https://blacklivesmatter.com/imagining-abolition-episode-3-the-abolitionist-pod/

This video is from the Black Lives Matter organization’s “Imagining Abolition” series, which explores some ways Black communities around the United States are imagining and embodying abolitionist futures. This episode features an “abolitionist pod,” a community garden and art project. The pod is capable of feeding hundreds of people for months, on top of being a community gathering space. The philosophy behind the pod is that inequality, including food inequality, is at the root of crime and the carceral state. The pod addresses existing issues and offers a glimpse into a world without them.

Imarisha, W., Brown, A. M., Thomas, S. R., & Institute for Anarchist Studies (Eds.). (2015). Octavia’s brood: Science fiction stories from social justice movements. AK Press.

This book is a compilation of short science fiction stories inspired by Octavia Butler. In the introduction, Walidah Imarisha lays out the concept of “visionary fiction,” science fiction with a radical leftist political perspective. According to Imarisha, visionary fiction (including Butler’s work) is incredibly important to social justice initiatives, as “it is only through imagining the so-called impossible that we can begin to concretely build it.”

Lloyd, V. (2016). Post-racial, post-apocalyptic love: Octavia butler as political theologian. Political Theology, 17(5), 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/1462317X.2016.1211296

In this journal article, Lloyd claims that New Age spirituality has political potential in opposition to the political paradigm of Christianity. He looks specifically at Earthseed as an example of this. He claims Earthseed as forming horizontal communities with intimate and flexible relationships. While he ultimately comes to the conclusion that Butler fails as a political theologian, I beg to differ.

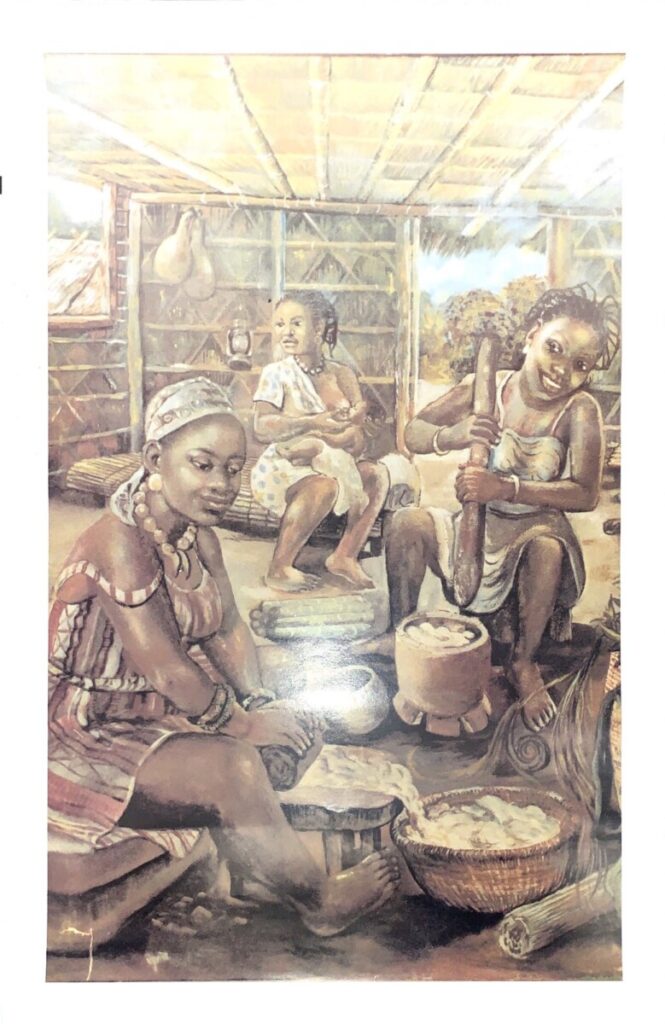

Mañana, J. La Cocina [Poster]. Richard A. Long posters, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University, Decatur, GA, United States.

This poster once belonged to Richard A. Long (1927-2013), an Africana historian based in Atlanta. To me, the image captures a meaningful and intimate moment in the construction of social units and the reproduction of culture. Cooking and other forms of domestic labor are critical in placemaking and building community autonomy. Black people in the United States tend to have far less access to land and food than their non-Black counterparts, and that has had far-reaching detrimental effects on the physical and social health of the population. Capturing the beauty of communal cooking helps center community and land in the radical imagination, recognizing them as the roots of our strength and joy.

McKittrick, K. (2006). Demonic grounds: Black women and the cartographies of struggle. University of Minnesota Press.

One of the more theoretical sources I draw from, Demonic Grounds is a book about Black women’s geographies. It frames all Black matters as spatial matters, highlighting the ways in which space in various forms (the plantation, the ‘hood, the prison, the country) are weaponized against Black people. McKittrick also details ways in which Black women have created homes for themselves within these spaces, often in ways that are in open conflict with the world around them. She comes to the conclusion that Black women are, in a sense, ungovernable, and that Black women’s placemaking is essential to the project of dismantling the state, capitalism, and White supremacy.

Purifoy, D. M. (n.d.). To live and thrive on new earths. Southern Cultures. Retrieved May 6, 2022, from https://www.southerncultures.org/article/to-live-and-thrive-on-new-earths/

An introduction to the Earthseed Land Collective and its members. Purifoy interviewed the members and asked about their goals and motivations. They demonstrate a commitment to the environment, their community, and each other in very spiritual terms. Purifoy also details some of the ways ELC parallels Butler’s work.

West, E. J. (2012). African spirituality in Black women’s fiction: Threaded visions of memory, community, nature, and being. Lexington Books.

This book argues that Black women’s fiction draws on the physical and experiential to explore matters of spirituality, and that this is culturally rooted in African practices. While it does not directly mention Butler, I have found it helpful in tracing some of the inspirations behind Butler’s fictional religion “Earthseed.” As the book suggests, fiction is used to transmit ideas and African spiritual concepts that inspire physical action and community-wide change. While African spirituality is implicit in Butler’s books, some members of the Earthseed Land Collective actively practice African religions.

Angel

Photo taken in Choco Colombia by Verónica Zaragovia for NPR

(https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2018/12/19/674291228/from-cocaine-to-cacao-one-mans-mission-to-save-colombia-s-farmers-through-chocol)

These are some of the sources I used in learning about Afro-Colombian communities on the Pacific Coast, their practices, and struggles.

Asher, K. (2004). Texts in context: Afro-Colombian women’s activism in the pacific lowlands of Colombia. Feminist Review, 78(1), 38–55. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.fr.9400189

This article complicates readings of post-colonial feminist theory by applying them to the lived concerns of Afro-Colombian women as gendered and racialized subjects. Looking largely at Black women’s organizations in the department of Cauca, Asher brings attention to these organizations and the women’s autonomy/self-determination to better their communities and lives. I am interested in how this article specifically addresses the tension between theory and praxis through a feminist lens.

Asher, K. (2009). Black and green Afro-Colombians, development, and nature in the Pacific lowlands. Duke University Press.

In this book, Kiran Asher delves into the complexities of green neoliberal development and local community autonomy. Rather than seeing these as contradictory, she argues that they shape each other through the development of state presence, Black rights, economic interests, and ecological conservation. I am interested in the depth of information within this book, especially her chapter titled “The El Dorado of Modern Times”: Economy, Ecology, and Territory.

Cámara-Leret, R., Copete, J. C., Balslev, H., Gomez, M. S., & Macía, M. J. (2016). Amerindian and Afro-American perceptions of their traditional knowledge in the Chocó biodiversity hotspot. Economic Botany, 70(2), 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12231-016-9341-3

This report attempts to document the traditional knowledge of Indigenous and Afro-Colombian inhabitants of the Chocó, a rainforest and biodiversity hotspot. Through their research they highlight different knowledge systems and find 46 useful palm species with 520 different uses. They also touch on the everyday use of traditional knowledge that gets it passed down and how that use is being shifted in the face of ongoing development and extraction. I am interested in this report because it documents and values ecological knowledge that would have been unknown outside of the community.

Cárdenas, R. (2012). Green multiculturalism: Articulations of ethnic and environmental politics in a Colombian ‘black community.’ The Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(2), 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.665892

This paper examines the combination of ‘green’ development movements and the rise of multicultural reforms. Rather than placing them as contradictory, Cardenas argues that they create a “political articulation” that he terms “green multiculturalism.” He suggests that green multiculturalism places the responsibility of protecting nature on Black agrarian communities and in turn transforms local efforts into entrepreneurial ones. I am interested to see how Cardenas values the labor implicit in his argument and whether green multiculturalism is a point of strength or stress on the communities he describes.

Grueso, L., Rosero, C., & Escobar, A. (2003). The Process of Black Community Organizing in the Southern Pacific Coast Region of Colombia. In M. C. Gutmann, F. V. Matos Rodrguez, L. Stephen, & P. Zavella (Eds.), Perspectives on Las Américas (pp. 430–447). Blackwell Publishers Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470753538.ch26

This chapter in Cultures of Politics/Politics of Cultures describes and analyzes the organization of Colombian southern pacific Black communities into social movements after the 1991 Law 70. It looks at how the 1991 constitutional reform influenced the development of collective mobilization and political organization through the lens of territory, ecology, and culture. It also gives a bit of background on the environmental, cultural, and economic history of the south pacific region and its relationship to the creation of identity.

Hernández Reyes, C. E. (2019). Black women’s struggles against extractivism, land dispossession, and marginalization in Colombia. Latin American Perspectives, 46(2), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X19828758

Through an analysis of the first national Mobilization for the Care of Life and Ancestral Territories (MCLAT), led by 40 Black women in the Colombian department of Cauca, this article looks at the lived experiences of Afro-Colombian women who’ve fought against the violence of racism, neocolonial extractivism, and land dispossession. Through a black/decolonial feminist lens, the article suggests that Afro-Colombian women’s historiocity and epistemology are central to understanding their resistance. I am particularly interested in this article because of the way it details the creation and first iteration of the MCLAT.

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada . (2018, June 5). Responses to information requests. https://irb.gc.ca:443/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?doc=458098

This report by the Canadian Immigration and Refugee Board gives a comprehensive overview of the presence and treatment of Afro-descendants in Colombia. It highlights the concentration of Afro-Colombians on the Pacific coast and cites various reports, surveys, and commissions to talk about employment, housing, state protections, confrontations with armed groups, treatment by authorities, and support services. This report was helpful for me in getting a base understanding of the Afro-Colombian inhabitants of the Pacific Coast.

Lobo, I. D., & Vélez, M. A. (2022). From strong leadership to active community engagement: Effective resistance to illegal coca crops in Afro-Colombian collective territories. International Journal of Drug Policy, 102, 103579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103579

This paper looks at the relationship between community leadership and effective community mobilization. The pacific region of Colombia has long been a used for the cultivation of illegal coca crops at the expense of local inhabitants, and this paper, through a series of surveys, interviews, and satellite imagery looks at how local groups with effective leadership have resisted this extraction. They argue that specific types of local leadership and community interest interactions are especially helpful to creating synergy among grass-roots organizations and local populations, and make suggestions for policy reorientation.

Losonczy, A. M. (1993). De lo vegetal a lo humano: Un modelo cognitivo Afro-Colombiano del Pacífico. Revista Colombiana de Antropología, 30, 38–57. https://doi.org/10.22380/2539472X.1708

This article highlights the interaction between culture and ecology for Afro-Colombians on the Pacific Coast. It argues that Afro-Colombians relationship to flora both shapes and is shaped by their cosmology and epistemology.

McLaren, I. (1996). Secrets of the Choco [Documentary]. Bullfrog Films.

This 1996 documentary goes into the Choco, one of the largest and (at the time) least disturbed rainforests in the world. It gives a survey of the rich and unique ecology largely unknown to outsiders but well maintained by the inhabitants. It also highlights how the Indigenous and Afro-Colombian inhabitants, despite living in poverty, have lived off the land and through interviews with them talks about how development projects are threatening the biodiversity of the area (despite claiming otherwise). The documentary raises questions about how best to preserve the rainforest while raising the standard of living for its inhabitants.

Pirsoul, N. (2017). Assessing Law 70: A Fanonian Critique of Ethnic Recognition in the Republic of Colombia. Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, 10(9). http://www.jpanafrican.org/docs/vol10no9/10.9-6-Pirsoul.pdf

This article is a critique of the limits of Colombia’s 1991 Law 70, which grants Afro-Colombians access to collective land titles (among other things). Pirsoul uses a fanonian framework to place Law 70 in a historical context that makes the law’s protection only a legal formality rather than an effectual change in governance and recognition of identity politics. Further, they state that the law can even further reproduce colonial relationships rather than disrupt them. I am deeply interested in this as a post-colonial fanonian critique.

Quintero-Angel, M., Coles, A., & Duque-Nivia, A. A. (2021). A historical perspective of landscape appropriation and land use transitions in the Colombian South Pacific. Ecological Economics, 181, 106901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106901

This paper looks at the history of land use and appropriation in the Colombian South Pacific across three periods, the colonial period, the rise of the independent liberal economy, and modern globalization. It looks at how changes were driven by different political regimes, changing labor laws, migration, population growth, modernizing technology, and diversity of crops/goods. I think this paper will be useful as a foundation for understanding the historical use, production, and extraction from the South Pacific region and may give insight to how other areas in the Pacific have been used.

Restrepo, E. (2011). Representaciones y prácticas asociadas a la muerte en los ríos Satinga y Sanquianga, Pacifico Sur Colombiano . Instituto Colombiano de Antropologia e Historia. http://www.ram-wan.net/old/restrepo/documentos/muerte%20santinga%20y%20sanquianga-restrepo.pdf

This article is an ethnography of conceptions and practices related to death of Afro-Colombians near the Satinga and Sanquianga rivers. Restrepo analyzes beliefs on burial practices, death and its causes, and looks at how the region has changed due to migration from narco traffickers. I am interested in this as a historical piece that analyzes communal practices and how culture is transformed by illegal cultivation.

Urrutia, L. G. M. (2015). El Choco: The african heart of Colombia [Speech]. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/El-Choco%3A-The-African-Heart-of-Colombia-Urrutia/0ea77f55a74e28aceba0b8f36d1cc951093a44f3

This speech was given by Luis Gilberto Murillo Urrutia, former governor of the department of Choco and later the director of the Colombian Presidential Initiative for the Development of the Pacific Region. In this speech Murillo Urrutia gives a brief history of the Choco and of Afro-Colombians in general, as well as outlining their present living situations and challenges. This speech is interesting because Murillo Urrutia represents a local government perspective speaking to groups such as the American Museum of Natural History, the Colombia Media Project, and the Caribbean Cultural Center.

Vélez-Torres, I. (2016). Disputes over gold mining and dispossession of local Afro-Descendant communities from the Alto Cauca, Colombia. Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal, 1(2), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2016.1229131

This article details the violent effects of Colombia’s neoliberal development practices through the example of mining in La Toma, Cauca. In 2001, mining legislation was introduced that made ancestral mining practices illegal at the same time as paramilitary groups moved into the territory for illicit extraction that terrorized the local population. I am interested in this paper for its part in historicizing Colombian legislation that harms Afro-Colombian populations.

Lastly, I wanted to include two pieces of music created by Pacific Afro-Colombians about their relationships to the land, one coming from a place of pride (Corazón Pacifico) and the other from disenfranchisement (Esta Tierra No Es Mia). The latter was released in 1998 by Sexteto Tabala, and the first in 2018 by Herencia de Timbiquí. I’ve also included the original lyrics and their translation for viewing ease.

Corazón Pacifico – Herencia de Timbiquí

Letra:

Tengo la fuerza de la tierra

El ímpetu del viento y la expresión del mar

Llevo la voz de los ancestros

El verde de la selva y el canto del manglar

El corazón profundo de mi litoral

La alegría eterna, canto y libertad

Mi sueño es con las mareas que vienen y van

Son los anhelos de mi gente y su verdad

Llevo muy dentro de mi pecho

El pulso de la vida y el golpe de un tambor

Tengo del África su alma

El espíritu del agua su magia y su pasión

El corazón profundo de mi litoral

La alegría eterna, canto y libertad

Mi sueño es con las mareas que vienen y van

Son los anhelos de mi gente y su verdad

Corazón pacífico (x20)

Lyrics:

I have the strength of the earth

The impetus of the wind and the expression of the sea

I carry the voice of the ancestors

The green of the jungle and the song of the mangrove

The deep heart of my coastline

Eternal joy, song and freedom

My dream is with the tides that come and go

They are the desires of my people and their truth

I carry deep inside my chest

The pulse of life and the beat of a drum

I have his soul from Africa

The spirit of water, its magic and its passion

The deep heart of my coastline

Eternal joy, song and freedom

My dream is with the tides that come and go

They are the desires of my people and their truth

Pacific Heart (x20)

Esta Tierra No Es Mia – Sexteto Tabala

Letra:

Esta tierra no es mía, esta tierra no es mía

Esta tierra no es mía, esta tierra no es mía

Esta tierra no es mía, esta tierra no es mía

Esta tierra no es mía, esta tierra es de la nación

El ingenio Santa Cruz es una cosa poderosa

Llegaron al desengaño y derrotaron todas las cosas

Llegaron al desengaño y derrotaron todas las cosas, si

(Coro)

Yo salí de cacería, lo que maté fue una lora

La perdición de Colombia desde que llegó a la historia

La perdición de Colombia desde que llegó a la historia, si

(Coro)

Llegó la reforma agraria con una cosa infinita

Y lo malo que ellos hicieron, que nos dejaron sin azúcar

Y lo malo que ellos hicieron, que nos dejaron sin azúcar, si

(Coro)

Llegaron Los Rinconeros, que ahora sí tenemos plata

Se paran en las esquinas, hablan de caballo y vaca

Se paran en las esquinas, hablan de caballo y vaca

(Coro)

Los señores palenqueros, lo digo con poca gana

Todo lo que aprovecharon fue la gente mala gana

Todo lo que aprovecharon fue la gente mala gana, sí

(Coro)

Llegaron al desengaño con una cosa que arrastra

Me dijo el doctor Cortázar: “Cassiani, vaya pa’ su casa”

Me dijo el doctor Cortázar: “Cassiani, vaya pa’ su casa”

Esta tierra no es mía, esta tierra no es mía

Esta tierra no es mía, esta tierra es de la nación (óyelo)

Esta tierra no es mía (Cartagena), esta tierra no es mía

Esta tierra no es mía, esta tierra es de la nación

Llegaron al desengaño con una cosa que arrastra

Llegó con tanta oranesa, Cassiani, vaya pa’ su casa

Llegó con tanta oranesa, Cassiani, vaya pa’ su casa, sí

(Coro)

Lyrics:

This land is not mine, this land is not mine

This land is not mine, this land is not mine

This land is not mine, this land is not mine

This land is not mine, this land belongs to the nation

Santa Cruz sugar mill is a powerful thing

They came to disappointment and defeated all things

They came to disappointment and defeated all things, yes

(Chorus)

I went hunting, what I killed was a parrot

The downfall of Colombia since it entered history

The downfall of Colombia since it entered history, yes

(Chorus)

The agrarian reform came with an infinite thing

And the bad thing they did, that they left us without sugar

And the bad thing that they did, that they left us without sugar, yes

(Chorus)

Los Rinconeros arrived, now we do have money

They stand on street corners, they talk about horse and cow

They stand on street corners, they talk about horse and cow

(Chorus)

The gentlemen of Palenque, I say it reluctantly

All they took advantage of was people reluctantly

All they took advantage of was people reluctantly, yeah

(Chorus)

They came to disappointment with a thing that drags

Doctor Cortázar told me: “Cassiani, go to his house”

Doctor Cortázar told me: “Cassiani, go to his house”

This land is not mine, this land is not mine

This land is not mine, this land belongs to the nation (hear it)

This land is not mine (Cartagena), this land is not mine

This land is not mine, this land belongs to the nation

They came to disappointment with a thing that drags

She arrived with so much oranesa, Cassiani, go home

She arrived with so much oranesa, Cassiani, go home, yes

(Chorus)