Peruvian pelicans inhabit the coastal areas of Peru and Chile and nest along the coast of Peru, as shown in the map above. They breed in large colonies on the rocky desert coasts and feed in the shallow offshore waters on small schooling fish, especially anchovies. They do not generally dive for food like other pelican species, but skim along the surface, using their gullet pouches like dipping nets. These blue striped pouches, which deepen in color during mating season, hold around three gallons of water and can expand a foot or more. The color blue was highly valued throughout Andean cultures and so would have added to the prestige of this animal as well.

Pelícanos (Pelecanus thagus), Piedra Playa de Calabocillos, Constitución 2012. Photo by Paulo Pérez Castro

Pelicans collect annually in large, crowded, breeding colonies. Once pairs have formed, both parents protect the nest, incubate the eggs, and care for the fledglings. Their reciprocity in raising young and close contact as a group exemplify the Andean concept of ayni, or dual interrelation of different but balanced parts to make a viable whole. Adults and juveniles use their bills in a variety postures, movements, and calls to communicate their intentions and warn trespassers away from nests. This elaborate system allows them to breed successfully in densely packed nesting sites – avoiding conflicts that could harm eggs and young.

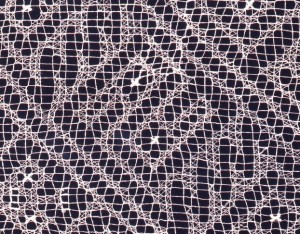

Openwork Headcloth with Pelican, Feline, and Snake Motif. Chancay, Central Andes, Central Coast. 1000-1450 AD. 1989.008.163. Gift of William C. and Carol W. Thibadeau. Photo by Michael McKelvey.

These impressive birds also fly and fish in large groups, thus their elaborate, well-regulated social life may have influenced this Chancay textile artist to feature rows of abstracted pelicans in pairs, one bird dovetailed with the other. The two bodies, one right side up to the other’s upside down orientation, epitomize ayni interlockedness. The zigzag of the pelican tails that punctuate the diagonal rows animates and electrifies the piece, but the overall framework is well organized – an idea reflected in strongly centralized, yet dynamic Andean political organizations. Most societies in this culture area, for instance, divided themselves into two large groups, known as moieties.

Detail of Openwork Headcloth. Chancay, Central Andes, Central Coast. 1000-1450 AD. 1989.008.163. Gift of William C. and Carol W. Thibadeau. Photo by Michael McKelvey.

Another orderly and cyclical duality occurs naturally in relation to the pelican. During some years unusually warm sea currents kill off small fish and plankton along the Peruvian coast, starving the birds who range inland to forage, before dying in large numbers. This regularly recurring reversal of the pelican’s symbolic role, from harbinger of fertility and abundance to bearer of destruction and death, would only have heightened their religious significance. Coinciding with the red tide that signaled the transformation of the Spondylus shell into a prized entheogen, the cyclical pelican “invasion” would have filled the ancient coastal cities with these enormous avians –allowing artists to experience them firsthand. The close relationship of humans to all animals, the basis of ayni, pervades Andean art, culture, and nature.