Rising from the Ashes

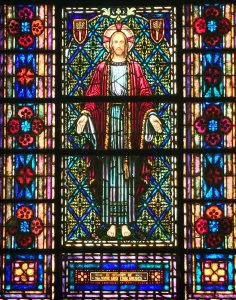

One of the most often remarked upon attributes of St. Luke’s United Methodist Church is the beauty of its sanctuary, most notably, its stained glass windows. One window in particular caught my eye the first time I entered the sanctuary as the new senior pastor—a phoenix, rising from the ashes.

The current worship space of this 108-year-old congregation in the heart of the Fondren neighborhood of Jackson, MS, is not the original sanctuary. It was built to replace the original church building, a small white-framed chapel, destroyed by fire in 1929. The membership, numbering around 100, decided instead of rebuilding the small white building, to build a larger, brick, neo-gothic sanctuary that would seat triple the number of the original building. This all took place during the first year of the Great Depression and the new sanctuary was dedicated one day short of the one-year anniversary of the fire.1

In the immediate years following, the church experienced a period of rapid expansion. Growing from a relatively small congregation that lost everything the church owned to a large neighborhood parish in just one decade is a powerful symbol of resurrection. The Phoenix window, in a place of prominence in the new sanctuary, was a lasting reminder of a church that literally rose again from the ashes. It adorned the sanctuary of a church that was dying once again. And I was sent to either bear witness to its resurrection or preside over its funeral.

The Church is Dying

As a pastor leading a United Methodist congregation I have spent most of the last ten years of my ministry reading about how the church in America is dying. And St. Luke’s, like so many others, was in a steep decline toward an apparent death.

I have been to conferences on best practices to reverse the trend. I have read numerous books on church revitalization. And while much of the literature invokes spiritual disciplines and sound theology I was struck by lack of any explicit appeal to resurrection. Furthermore, there was never any clear sense of the reason why we should work to revitalize our churches at all. Do we work to revitalize a particular congregation out of a sense of nostalgia or to reassert cultural relevance? Much of the literature was simply evangelically motivated; we revitalize churches so that we can save souls. But save them for what? I contend that we work to revitalize local congregations, and all that entails, in order to embody resurrection to the world. With this belief I set out to explore the theological and scriptural significance of the resurrection of Jesus in service of church renewal.

The Jewish Roots of Resurrection

Kevin J. Madigan and Jon D. Levenson offer a sweeping examination of the shared theology of resurrection among Jews and Christians. Against any misconception that the concept of resurrection was a novel theme among the followers of Jesus in the first century C.E., Madigan and Levenson endeavor to show that the hope of resurrection has deep Jewish roots.

They highlight particularly the “restoration eschatology” of the second temple period: arising out of exilic and post-exilic reflections on the experience of loss and foreign domination. What emerges is the belief that “the God of Israel would reclaim his throne, his capital city Jerusalem would be restored, and his palace, the Temple, rebuilt.”2 Most notable was the belief that there would be a general resurrection of the dead accompanying a judgment by God.3

In this light, we can see the theological perspective out of which Jesus’ followers came to interpret his own death and resurrection.4 First-century Christians were interpreting what they understood to be Jesus’ bodily resurrection as a sign that the present age was ending and that the “long-promised restoration had begun.”5 Rather than a novel idea in the tradition, Jesus’ resurrection is only properly understood in the context of Israel’s eschatological hope.

The apostle Paul translated the eschatological theme of resurrection into a matter of ecclesiology. He picks up the theme of the eschatological hope through Jesus’ resurrection when he equates the church to a body. Just like Israel, Paul suggests, the church is a body, a collective unit made up of its constitutive members. The individual members of the church, together, are the body of Christ. And, just as God raised Jesus from the dead, so too the church, which makes up the body of Christ, will be raised.6

The Power of Resurrection in the Life of The Church

N.T. Wright likens the work of the church, in light of the resurrection, to that of building a great cathedral. The work of preceding generations is built upon in the present, and the work will undoubtedly go on into the future.7 Ultimately, the work of construction is guided by the finished design, which in the present can only be glimpsed in partiality. Therefore, even if the work is not completed in one’s own mortal lifespan the work is not in vain, particularly because the hope of resurrection is also the promise that our work in the present will find its way into the new creation of God’s new heaven and new earth. As Wright puts it so captivatingly, “God’s recreation of his wonderful world, which began with the resurrection of Jesus and continues mysteriously as God’s people live in the risen Christ and the power of the Spirit, means that what we do in Christ and by the Spirit in the present is not wasted.”8

Rowan Williams argues that it is precisely through the church that the risen Christ is experienced. The church’s existence is a witness to the historical event of the resurrection of Jesus and it is also the place where Jesus’ body is now met.9 He notes that in the Acts of the Apostles, none of the apostles seem bothered that Jesus has ceased his post-Easter bodily appearances. Instead, by the power of the Spirit, they experience the risen Christ in the community of faith.

They continue to do mighty acts in his name, and his power is available to them, even the power to raise others from the dead.10 This is the core of the apostolic faith in the early church. Williams writes, “to believe in the risen Jesus, is to trust that the generative power of God is active in the human world; that it can be experienced as transformation and recreation and empowerment in the present; and that it’s availability and relevance extends to every human situation.”11 Whatever power the church has in this world, whatever hope for renewal or revitalization, whatever belief that its work has lasting value; is irrevocably connected to the reality that the church is Jesus’ body, and that body has been raised.

A Bible Study on Resurrection

In the New Testament, resurrection is not a theoretical idea or instructional metaphor. It is a real, embodied event that involves real dead bodies coming back to a living state. And notably, Jesus’ bodily resurrection becomes the foundational claim of subsequent Christian proclamation.12 The essential nature of Jesus’ resurrection can be seen, for instance, in the very narrative structure of the Luke-Acts literature. Luke’s resurrection account occurs in chapter 24. It occurs, not just at the end of the Gospel, but also at a significant turning point in the theological argument of the Luke-Acts sequence. Luke imagines three stages of salvation history.13 It begins with the story of Israel, recounted in the Law and the prophets (see Luke 16:16). The story continues in Jesus who is loyal to Israel, thus ensuring that God has not changed the divine plan, but fulfilled it in him. The Jesus story dominates from Luke 3:1 through Acts 1:26. This gives way to the story of the church, empowered by the Spirit to bear witness to the Son to the ends of the earth. Jesus is the centerpiece binding together Israel and the Church.14 Thus Luke 24, bearing witness to the resurrection of Jesus, is center-point of the Lukan salvation history.

As a way of introducing my congregation to the idea that church revitalization at St. Luke’s is empowered by the resurrection of Jesus Christ, I held a series of bible studies in a variety of settings; all based around three core texts: Luke 7:11-17 (The Raising of the Son of the Widow of Nain), Luke 24:13-15 (The Walk to Emmaus), and Acts 9:36-43 (The Raising of Tabitha).

In these stories, we see the evangelist’s belief that the church participates in the power of Jesus by embodying resurrection to the world. The power of resurrection serves a significant dual function of undergirding the missiological and evangelistic purposes of the church. In raising the widow’s son to life, we see that Jesus has the power to raise people from the dead. In the encounter at Emmaus, we see that Jesus himself has conquered death and invites the disciples to share in his life through shared word and broken bread. In Peter’s raising of Tabitha from the dead, we see that the church is now empowered to bring life from death so that the work of the church may continue. As a result of resurrection the mission of the church can continue, even in the face of death, and many will come to believe in Jesus as a result.

A History of Resurrection

What emerged from mutual study of scripture and an examination of the history of St. Luke’s, was that the church has believed and practiced through its life as a congregation that faith in Jesus Christ should manifest itself in this world through practices that bring healing, restoration, and that ultimately embody resurrection.

In fact, studying the history of St. Luke’s in light of the theological and scriptural witness has revealed a cycle of growth, decline, and resurrection. This “resurrection history” of St. Luke’s provides a new narrative of self-understanding that not only looks back, but serves as a story that propels the mission of St. Luke’s forward.

To read that new resurrection narrative visit St. Luke’s online history. Click Here.

In the past 8 years St. Luke’s has experienced a resurrection. Listen to some voices of St. Luke’s, surrounded by the windows that remind them of their story. These clips are taken from a longer video produced for St. Luke’s first-ever capital campaign to renovate its facilities.

What’s Next?

I intend to use my insights from this project to encourage my church to continue to narrate its story through the lens of resurrection. One tangible way that I have already begun to implement this is through our new member class. Once a quarter new and prospective members are invited to attend a series of classes on the history, beliefs, and mission of St. Luke’s United Methodist Church. Rather than a history based solely on dates, we move through our history through the cycle of death and resurrection. I intend to also make this a yearly focus of a sermon series.

For those who have just arrived to St. Luke’s, or the neighborhood, it could be easy to think the events of the last several years are unique or a surprising anomaly; however, for those with ears to hear the story that the people of St. Luke’s have lived it is no surprise. It is instead the living embodiment of the story of a people who believe in the power of resurrection, the power of God that can bring life from death. It is the story of those who put their faith in Jesus Christ, and who live out that faith through good works of compassion, justice, and mercy; thereby embodying resurrection.

1. The date and story of the burning of the original church building are taken from a commemorative photo and plaque that hangs in the foyer of the current church.

2. Kevin J. Madigan and Jon D. Levenson, Resurrection: The Power of God for Christians and Jews (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 5.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid., 20.

5. Ibid., 23.

6. Ibid. 32.

7. N.T. Wright, Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church (New York: HarperOne, 2008), 210.

8. Ibid., 208.

9. Rowan Williams, Resurrection: Interpreting the Easter Gospel (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Morehouse Publishing, 1994), 104.

10. Ibid., 118.

11. Ibid., 49.

12. William H Willimon, “Preaching as Demonstration of Resurrection,” Journal for Preachers 38, no. 3 (2015): 6–10.

13. Raymond Edward Brown, An Introduction to the New Testament, 1st edition, Anchor Bible Reference Library (New York: Doubleday, 1997), 228.

14. Ibid., 272.

Save