BOUNDARY LEADERSHIP AT EMORY

The past three years of course work and research in the Emory University community have deeply shaped my view of how community is formed and how people find places of belonging. This research has also demonstrated the need for remarkable, adaptive leaders in this community. Author and researcher Gary Gunderson calls this “Boundary Leadership,” which “is the practice of leadership in the boundary zone, the space in between settled zones of authority, where relationships are more fluid, dynamic, and itinerant.”1

Boundary leaders at Emory play a critical role in helping marginalized students to find belonging, build community and connections, make meaning, learn resiliency, and have a lasting, sustainable impact in both the Emory community and the communities in which they find themselves after college.

Boundary leadership helps build vibrant,  thriving communities of inclusion, wholeness, and mutual prosperity. In the Christian tradition, this is exemplified in the in-breaking Kingdom of God made manifest through our loving actions. Boundary Leaders work intentionally in and between fluid communities to connect people to institutions, associations, and movements so that all community members can live out their passions, abilities, and embodied practices of life. They are fluent in a variety of “languages” and cultures, confident in their own self-understanding, and willing to risk and cross over traditional boundary lines in service of the whole of the community.

thriving communities of inclusion, wholeness, and mutual prosperity. In the Christian tradition, this is exemplified in the in-breaking Kingdom of God made manifest through our loving actions. Boundary Leaders work intentionally in and between fluid communities to connect people to institutions, associations, and movements so that all community members can live out their passions, abilities, and embodied practices of life. They are fluent in a variety of “languages” and cultures, confident in their own self-understanding, and willing to risk and cross over traditional boundary lines in service of the whole of the community.

Authors Stephen Preskill and Stephen Brookfield write in Learning as a Way of Leading, that “leadership itself is a normative practice focused on the project of increasing people’s capacity to be active participants in the life of their communities, movements, and organizations.”2 Boundary leaders’ asset-based community development strategies are a systems-level and yet on-the-ground way of thinking while moving in and between organizations and structures–places where change is the only constant and where their unique skills and adaptations are absolutely essential.

Boundary leaders have specific strengths and characteristics: a broad web of relationships, resiliency, imagination, a capacity to see “patterns of possibility,” and great “organizational intelligence.”3

They are uniquely adapted to the margins, edges, and spaces between—they see these conditions as powerful opportunities to foster meaningful change in communities.4 Learning the theory and practice of Boundary Leadership does not begin with global icons, but through interaction with and careful observation of the pattern of the lives of people in our communities who do community organizing, community development, and facilitate places and structures of belonging for everyday people.5 This project sought to learn from local boundary leaders and to share how they move and work in the Emory community.

Pre-Week 1 Video: Intro to Boundary Leadership (DMin Final Project 2017) from Joseph McBrayer on Vimeo.

THE PROJECT: CREATING A DIGITAL, VIDEO-BASED CURRICULUM

The two goals of this project were: 1) to learn and understand how boundary leaders function on the Emory University campus and 2) to create a media rich, digital, video-based curriculum on boundary leadership for use in a college ministry setting. The video interviews of eight practicing boundary leaders on campus documented how they operate in community, take care of themselves, see the world around them, and perceive their work as leaders in the Emory community. The information collected from the interviews increased my understanding of boundary leadership, grew my skills at video and camera work in digital storytelling, and taught me a great deal about creating a digital curriculum.6

The resulting curriculum was used with a pilot group to teach boundary leadership concepts, demonstrate the importance of boundary leadership in community formation, social action and positive systemic change, and to show the opportunities for boundary leadership in our communities.

The creation of this media rich, digital, video-based curriculum on boundary leadership was itself a practice of boundary leadership,

which taught me to be a better boundary leader and allowed me to test the theories of boundary leadership with the opportunities awaiting boundary leaders in community.

REFLECTION ON THE RESEARCH PROCESS

The Video Interviews

Through my previous research at Emory, I identified and selected eight experienced and emerging boundary leaders to interview. These interviews were captured through skilled and stylistic video camera operation and editing techniques that required a deep understanding of conducting video interviews in order to tell the story of boundary leadership on campus. After filming, the interviews were processed, transcribed, and edited into a video-based, small group curriculum to share the experiences and learnings of these boundary leaders with the pilot group.

Filming the Interviews

The video interviews required a great deal of intentional planning and provided an opportunity for learning more about the craft of interviewing and deep listening, camera work, editing, post-production, and a variety of other technological proficiencies.

The video interviews required a great deal of intentional planning and provided an opportunity for learning more about the craft of interviewing and deep listening, camera work, editing, post-production, and a variety of other technological proficiencies.

The act of participating in a video interview is by its very nature an intimate and potentially risky endeavor as what is said will be recorded and analyzed.

As a result, building and maintaining connection with the interviewee is vitally important.

The interviews were conducted in a studio environment created in my office where all camera, audio, and lighting equipment, along with backdrops and atmospherics were set up and ready for each interview.7 This space helped to visually convey the expertise of the subjects and the warm feel of a learning environment. Media theorist Marshall McLuhan rightly noted years ago that “the medium” of our communication is “the message.”8

In communicating through video and film we must be aware that the visual and auditory environment presented can contribute to or detract from the communication of that message

so it was essential that each of the three camera angles be framed properly and that the audio be free of distractions. Each 60-90 minute interview consisted of filming “B-roll” video9 on campus, walking the campus and filming, and the in-studio interview. Significant time was also needed before and after each interview for setup, interview content and camera preparation, offloading data/media, planning out shots and filming routes between locations, and other technical and content specific details.

Conducting interviews is a science and an art as the interviewer must diligently prepare for each interviewee by crafting insightful questions, which capture the unique expertise of the interviewee and draw him or her into answering the questions with genuine responses and stories. The artistic side of the process necessitates that the interviewer remain open to change the direction of the interview based on the interviewee’s responses. The act of conducting these interviews was an opportunity for boundary leadership in identifying and researching interviewees, organizing and planning the interviews, and filming and conducting the interviews.10

Conducting interviews is a science and an art as the interviewer must diligently prepare for each interviewee by crafting insightful questions, which capture the unique expertise of the interviewee and draw him or her into answering the questions with genuine responses and stories. The artistic side of the process necessitates that the interviewer remain open to change the direction of the interview based on the interviewee’s responses. The act of conducting these interviews was an opportunity for boundary leadership in identifying and researching interviewees, organizing and planning the interviews, and filming and conducting the interviews.10

The Pilot Group

The main educational goal of this project was the creation of a digital, video-based  curriculum on boundary leadership to be piloted in a group of undergraduate students in a collegiate ministry setting. The interviews provided a rich, visually compelling roster of content and presented the additionalchallenge of deciding which content was the most pertinent and potentially transformative. Pilot group participants noted that the content and style of the curriculum and videos worked well to maintain interest and communicate effectively.11

curriculum on boundary leadership to be piloted in a group of undergraduate students in a collegiate ministry setting. The interviews provided a rich, visually compelling roster of content and presented the additionalchallenge of deciding which content was the most pertinent and potentially transformative. Pilot group participants noted that the content and style of the curriculum and videos worked well to maintain interest and communicate effectively.11

The pilot curriculum consisted of three weeks:

- Week 1: Introduction to Boundary Leadership, Boundary Zones, and Relationships.

- Week 2: Learning as a Way of Leading, Imagination and Ways of Seeing, and Self-Care.

- Week 3: Resiliency, Belonging and Community, and Action.

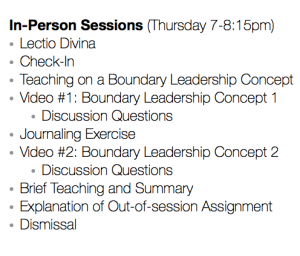

The curriculum’s format consisted of three, 75-minute, in-person sessions with both pre- and post-session assignments and videos to augment the learning process. Each Tuesday, a link to a 5-7 minute video was sent over email and text message for participants to watch prior to the in-person session on Thursday Night.

The in-person sessions were hosted in my  office with comfortable chairs, a coffee table, and a flat screen television for videos and slides as the focal point. The familiar space offered a safe, respected learning environment for the participants. Each session began with a contemplative practice of Lectio Divina, centering on a story of Jesus’ boundary leadership found in the Gospels.12 This time demonstrated the kind of contemplative practices and self-care needed in boundary leadership and was a way to center and focus our pilot group. The group then moved into a time of “check-in” with refreshments and conversation on the pre-week video, the out-of-session assignment, and how it all intersected with the contemplative practice. I then taught briefly on boundary leadership, which set up the next video. After the video, participants engaged a set of discussion questions and then engaged in a journaling exercise and time of quiet reflection.13 This helped to transition to the second video

office with comfortable chairs, a coffee table, and a flat screen television for videos and slides as the focal point. The familiar space offered a safe, respected learning environment for the participants. Each session began with a contemplative practice of Lectio Divina, centering on a story of Jesus’ boundary leadership found in the Gospels.12 This time demonstrated the kind of contemplative practices and self-care needed in boundary leadership and was a way to center and focus our pilot group. The group then moved into a time of “check-in” with refreshments and conversation on the pre-week video, the out-of-session assignment, and how it all intersected with the contemplative practice. I then taught briefly on boundary leadership, which set up the next video. After the video, participants engaged a set of discussion questions and then engaged in a journaling exercise and time of quiet reflection.13 This helped to transition to the second video on boundary leadership, which was followed by discussion. At the end of each session there was a brief summary teaching and a community-based, post-session assignment, which led into the next week’s content. The first was an exercise to observe boundary zones and think about ways to strengthen the community. The second was a “Spiritual PhotoWalk”created as an awareness practice where participants moved across campus as they captured images on their phones, reflected upon the images, and shared their findings with a friend or on social media.14 Participants responded that the out-of-session assignments were helpful to put boundary leadership concepts into practice—providing needed practice in different ways of seeing and being aware of the boundary zones around them.

on boundary leadership, which was followed by discussion. At the end of each session there was a brief summary teaching and a community-based, post-session assignment, which led into the next week’s content. The first was an exercise to observe boundary zones and think about ways to strengthen the community. The second was a “Spiritual PhotoWalk”created as an awareness practice where participants moved across campus as they captured images on their phones, reflected upon the images, and shared their findings with a friend or on social media.14 Participants responded that the out-of-session assignments were helpful to put boundary leadership concepts into practice—providing needed practice in different ways of seeing and being aware of the boundary zones around them.

MAJOR FINDINGS AND IMPLICATIONS

Observed Characteristics and Strengths of Boundary Leaders

This project confirmed Gunderson’s theories and observations of boundary leadership and it was clear that each interviewee possessed the core strengths of boundary leadership: a broad web of relationships, resiliency, imagination, a capacity to see “patterns of possibility,” and great “organizational intelligence.”15

Relationships

The depth of their webs  of relationship was made clear while filming on campus as each interviewee saw people he or she knew, waved to, and/or with whom they stopped to talk.16 Interviewees shared about the importance of relationships in their work in the Emory community with one saying, “Relationships are foundational to everything that I do—we can’t do any of this work on our own”17 and another noting that “Networks [of relationships] are really life webs and without them we’re not sustainable.”18 Another interviewee remarked,

of relationship was made clear while filming on campus as each interviewee saw people he or she knew, waved to, and/or with whom they stopped to talk.16 Interviewees shared about the importance of relationships in their work in the Emory community with one saying, “Relationships are foundational to everything that I do—we can’t do any of this work on our own”17 and another noting that “Networks [of relationships] are really life webs and without them we’re not sustainable.”18 Another interviewee remarked,

“Relationships are how I make sense of the world—it feels very organic and almost like breathing to get to know people. It’s hard for me to picture living without relationships being central to how I move.”19

Resiliency

Another key strength of boundary leaders is resiliency: the ability “to withstand or recover quickly from difficult conditions.”20 Gunderson notes that boundary leaders are resilient “because they have high tolerance for ambiguity and excellent survival skills” and, while they do perceive the brokenness amongst the boundary zones, they “are not defeated by either the powerful interests that create the pain or by the divisions that threaten to obstruct progress.”21 The interviewees possessed unique skills as a result of their challenging life experiences, which allow them to know how to care for people going through those very life experiences and difficulties.22 One interviewee remarked, “Resiliency is really about coming to the conclusion that you are worth fighting for more than once” and that your own person –your very self—is worth your own attention and intentional time spent in self-care.23

Imagination

Boundary leaders “have strength of imagination, a subtle capacity to see what could be.”24 This capacity for imagination allows boundary leaders to see things differently: where most people see challenges or problems to be fixed, boundary leaders see the assets, gifts, and opportunities in each person, place, and community.

Boundary leaders “have strength of imagination, a subtle capacity to see what could be.”24 This capacity for imagination allows boundary leaders to see things differently: where most people see challenges or problems to be fixed, boundary leaders see the assets, gifts, and opportunities in each person, place, and community.

Boundary Leaders are not unrealistic about the needs of a community nor do they ignore the challenges and wounds in a community, but rather they use their community-centric, imaginative, socially-interconnected creativity to perceive what might be in a community.25

The interviewees possessed ways of seeing that were simultaneously realistic and creative as a result of their life experiences and webs of relationships. In these ever-changing boundary zones “Imagination is what makes it possible for webs of transformation formation to emerge out of chaos.”26

Capacity to See Patterns

Boundary leaders “act as midwives to the imagination, listening, reflecting, and looking carefully for patterns and people and power.”27 They are able to see and understand the world around them in ways that help them to recognize patterns in the systemic structures and know how to live, survive, and even thrive on the margins. These interactions can most easily be seen and navigated through deep webs of relationship, which help boundary leaders to visualize and understand from an individual level to the systemic.

Organizational Intelligence

This systems-level perspective allows boundary leaders to have “organizational intelligence” and the ability to navigate complex situations with the powers that be.28 The interviewees demonstrated that they know how to “dance” with the institutional forces to keep the “lights on” and grant money coming in for their programs and projects. And, despite their many relationships, time commitments, and job responsibilities, these boundary leaders maintain an unshakable focus on the importance of the people, the stories, and the communities in which they live, move, and work.

UNEXPECTED FINDINGS

Curiosity

One unexpected strength present in these leaders was that of curiosity. A key conversation that emerged from the interview questions on imagination was that of curiosity—specifically the “but why?” question. Gunderson writes that two essential questions lead us into the boundary zones: “But why?” and “So what?” 29 Curiosity places these questions in our minds and true leadership takes place in living out this curiosity. In Learning as a Way of Leading, the authors write that

the foundational first task of leadership is “learning how to be open to the contribution of others” and that this task truly begins with a genuine interest in other people’s and group’s experiences, stories, and gifts.30

The interviewees possessed a strong desire to learn about the people, groups, histories, and stories in their communities. As a result of their ability to see differently, these boundary leaders have been able to use their creativity and curiosity to help transform communities and the lives of the people therein.

Art as Boundary Leadership

Several interviewees responded that the making and sharing of art was important to their work and that it can serve as both a response and call to the community. They noted that the act of making art or music was both an expression of the community as well as their own self understanding.31 One interviewee, speaking about the intersection of art, activism, and community building, said, “The role of an artist is to translate the longings of the heart of the people” and that

Several interviewees responded that the making and sharing of art was important to their work and that it can serve as both a response and call to the community. They noted that the act of making art or music was both an expression of the community as well as their own self understanding.31 One interviewee, speaking about the intersection of art, activism, and community building, said, “The role of an artist is to translate the longings of the heart of the people” and that

“When people see your work as an artist, they are visualizing their own hope.”32

From these remarks and the subsequent conversations, the powerful nature of a community’s hopes expressed through art, music, and other media became an unanticipated and rich discussion of boundary leadership. Others shared that art was a personal practice of contemplation, rest, and imagination as well as a public good to express the culture and hopes of the community. The pilot group participants thoroughly enjoyed this perspective of art as boundary leadership.33

Self-Care and Spirituality

Another powerful observation is that the  self-care and resiliency skills of the more experienced boundary leaders appeared notably stronger than that of the emerging boundary leaders. This is most likely due to the immense importance of self-care in doing this work for the long haul. As one interviewee noted, a deep sense of self-awareness and knowing when you need to rest is absolutely essential to this work.34 Another remarked, “Good boundary leaders are people who are contemplative, who have been able to include the contemplative in their life—practices that slow them down.”35

self-care and resiliency skills of the more experienced boundary leaders appeared notably stronger than that of the emerging boundary leaders. This is most likely due to the immense importance of self-care in doing this work for the long haul. As one interviewee noted, a deep sense of self-awareness and knowing when you need to rest is absolutely essential to this work.34 Another remarked, “Good boundary leaders are people who are contemplative, who have been able to include the contemplative in their life—practices that slow them down.”35

For boundary leaders—regardless of their faith tradition—spiritual practices of contemplation or prayer, reflection, and stillness help propel these leaders into the community—these practices of reflection and contemplation help ground boundary leaders in Love and in their true selves.36

From this place of stillness and stability boundary leaders find belonging and from that springs a “communal capacity to resist and risk.”37 This point resonated with the pilot group who responded that the most meaningful content of the curriculum centered on resiliency, self-care, and different ways of seeing including art, curiosity, and imagination.38

From this place of stillness and stability boundary leaders find belonging and from that springs a “communal capacity to resist and risk.”37 This point resonated with the pilot group who responded that the most meaningful content of the curriculum centered on resiliency, self-care, and different ways of seeing including art, curiosity, and imagination.38

WHAT’S NEXT

Finishing the Digital and Online Curriculum

This project has been a complex, challenging, and very rewarding experience and experiment in boundary leadership. It is the culmination of a three-year process of identifying, researching, learning, evaluating, planning, reflecting, and implementing practices of boundary leadership in the Emory University community.

The process to discover, discern, and recruit interviewees for this project was itself a practice of boundary leadership in pulling together the people and community resources to accomplish the creation of this curriculum.

The multifaceted, intricate dimensions of this project necessitated a resiliency borne of a supportive community of family, friends, colleagues, professors, and classmates who gave of their time, energy, expertise, and encouragement along the way. The interviewees’ investment of time, energy, and insights have been an incredible gift to this project and to my own learning about their lives, experiences, stories, and practices of leadership in the boundary zones. This project was a remarkable opportunity to test, evaluate, and contextualize the concepts and theories of  boundary leadership in an observable, tangible, visually engaging, creative, and transformative way.

boundary leadership in an observable, tangible, visually engaging, creative, and transformative way.

The next steps for this curriculum are to refine it into a free, downloadable, and online version, which could be used by collegiate ministry professionals, local churches, denominational agencies, non-profits, book clubs, and small groups. The videos and the curriculum will require additional editing, formatting, and adjustment to meet these goals.

Boundary leaders, with their strengths in relationship building, resiliency, creativity, curiosity, imagination, pattern recognition, and organizational intelligence are needed more than ever to help our communities navigate the chaotic times and immense opportunities for transformation in our communities, our church, our nations, and our world.

___

Footnotes:

1 Gary R. Gunderson and James R. Cochrane, Religion and the Health of the Public (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), Kindle edition, 119-120.

2 Stephen Preskill and Stephen D. Brookfield, Learning as a Way of Leading: Lessons from the Struggle for Social Justice (San Francisco: Wiley, 2009), 61.

3 Gary R. Gunderson, Boundary Leaders: Leadership Skills for People of Faith (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004), Kindle edition, location 927.

4 Ibid., location 923.

5 Gunderson, Religion and the Health of the Public, 128.

6 Much of this early ethnographic work was deeply informed and shaped by two sources: Mary McClintock Fulkerson, Places of Redemption: Theology for a Worldly Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), Kindle Edition, and Mary Clark Moschella, Ethnography as a Pastoral Practice An Introduction (Cleveland, Ohio: The Pilgrim Press, 2008).

7 All of the interviews on Emory’s Atlanta campus were conducted in this manner and the interview with Rev. Lyn Pace was conducted in his office on the Oxford College campus in Oxford, GA with a similar atmospherics and filming set up.

8 Marshall McLuhan, The Medium is the Massage (New York: Bantam Books, 1967), 10.

9 “B-roll” is common video and film language for supplemental or alternative footage added into videos used as establishing shots or cut-a-ways. David K. Irving and Peter W. Rea, Producing and Directing the Short Film and Video (New York: CRC Press, 2014), 172.

10 I am indebted to Dr. Elizabeth Corrie for pointing this out during the planning phase of this project and for encouraging this understanding of videography and interview as ministry.

11 Joseph McBrayer, “Boundary Leaders Feedback (Pilot Group),” a survey sent to pilot group participants, February 2017, question 5.

12 Lectio Divina in Marjorie J. Thompson and Evan B. Howard, Soul Feast: An Invitation to the Christian Spiritual Life(Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2005), 24.

13 This activity was designed to help the more introverted students to process and reflect each session and the author is grateful to Dr. Corrie for suggesting it during one of our consultations.

14 The “Spiritual PhotoWalk” hand out was created by the author as a part of the coursework in DM714, Spring 2016.

15 Gunderson, Boundary Leaders, location 927.

16 The author has known many of the interviewees for several years and has even walked with many around campus previously, but not until filming and interviewing these leaders had the author witnessed such a visible and tangible sign of their webs of connectedness and relationships.

17 Danielle Bruce Steele, interview by author, December 2016.

18 Dr. Bobbi Patterson, interview by author, December 2016.

19 Ruth Ubaldo, interview by author, December 2016.

20 The New Oxford American Dictionary (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), Kindle edition, location 701327.

21 Gunderson, Boundary Leaders, locations 1032-1035.

22 Ibid., location 1059.

23 Carlton Mackey, interview by author, December 2016.

24 Gunderson, Boundary Leaders, locations 1083-1084.

25 Ibid., location 1089.

26 Ibid., locations 1086-1087.

27 Ibid., location 1090.

28 Ibid., location 1159.

29 Ibid., location 345.

30 Preskill, Learning as a Way of Leading, 15.

31 Ruth Ubaldo, Carlton Mackey, and Danielle Bruce Steele, interviews by author, December 2016.

32 Carlton Mackey, interview by author, December 2016.

33 This insight into the interconnectedness of art, curiosity, learning, and leadership was a potent and unforeseen aspect of these interviews and may serve as an avenue for a continuing conversation on boundary leadership through the arts.

34 Bobby Patterson, interview by author, December 2016.

35 Lyn Pace, interview by author, November 2016.

36 Gunderson, Boundary Leaders, location 1624—specifically Gunderson’s discussion of spiritual competencies and the chart in Figure 6, location 1633. This premise held true even for interviewees who do not identify with a particular faith tradition at all—it preliminarily appears that secular practices of contemplation and reflection can also contribute to an inclusive, Interfaith/Non-faith understanding of boundary leadership and this may merit further research.

37 Bobbi Patterson, interview by author, December 2016.

38 Joseph McBrayer, “Boundary Leaders Feedback (Pilot Group),” a survey sent to pilot group participants, February 2017.

Save

Cool! I can’t wait to see the other videos. This looks really well done.

Pingback: Boundary Leadership: a Video-Based Small Group Curriculum – JMcBray