Why the Meal?

When I was a child living in Georgia, my family would pile in the minivan to drive to Florida to visit my grandparents several times a year. No matter what time of day or night our van arrived, my Italian grandmother would open her door with instructions to wash our hands and meet at the kitchen table. Once we gathered at the table, we started to pass around bowls of ziti and gravy, bread, and salad and we would all eat until we were about to pop. The meal was always fabulous, but more than the food, I knew I belonged at that table.

I am a pastor at Johns Creek United Methodist Church. This is a young church in a city that is only ten years old. Johns Creek, GA is currently including residents in a visioning process to plan for the future. The city is looking to define its identity. In a community that is still forming places of belonging, I wanted to know if gathering around the table during the midweek meal could provide the same sense of belonging that I felt around my grandmother’s table.

I am a pastor at Johns Creek United Methodist Church. This is a young church in a city that is only ten years old. Johns Creek, GA is currently including residents in a visioning process to plan for the future. The city is looking to define its identity. In a community that is still forming places of belonging, I wanted to know if gathering around the table during the midweek meal could provide the same sense of belonging that I felt around my grandmother’s table.

What is it about table fellowship that creates a unique place of belonging?

Though a fellowship meal may seem like a mundane thing to study in light of other areas of theological exploration, “in recent decades scholars have embraced the fact that a real understanding of American religious phenomena cannot focus only on doctrines, leaders, and institutions but must also include the vernacular beliefs and practices of members.”1 It is important to recognize the lived practices of a congregation because these practices shed light on what members of the congregation consider to be important parts of being in community together. This project explores physical expressions of faith through table fellowship and the work that goes into making the midweek meal a viable ministry.

Explanation of the Project

In this project, I wanted to find out if the midweek meal at Johns Creek UMC (and thus, midweek meals in congregations similar to Johns Creek UMC) provides a place of belonging in the church.

Peter Block describes the importance of belonging in his book, Community, The Structure of Belonging:

“The need to create a structure of belonging grows out of the isolated nature of our lives, our institution, and our communities. The absence of belonging is so widespread that we might say we are living in an age of isolation…Ironically, we talk today of how small our world has become, with the shrinking effect of globalization, instant sharing of information, quick technology, workplaces that operate around the globe. Yet these do not necessarily create a sense of belonging. They provide connection, diverse information, and an infinite range of opinion. But all this does not create the connection from which we can become grounded and experience the sense of safety that arises from a place where we are emotionally, spiritually, and psychologically a member.”2

Through interviews, survey’s, research of past behaviors in the city and church and observation of the ministry I looked to find where and how the midweek meal serves as a place where people are emotionally, spiritually, and psychologically members.

Johns Creek, GA moved from an area dependent on the agricultural industry to an affluent area built by industries of technology and business. While places of belonging were family farms, general stores and trading posts in the past, there is currently no city center in Johns Creek, and so the places of belonging in the community are found in individual, often gated and private, neighborhoods or country clubs.

Johns Creek UMC has worked to grow with the community building physical space as well as ministries that answered needs of the people who were moving to Johns Creek. For example, a giant education building with a two-story indoor playground and several fields provides space for preschool and recreation ministries that provided a place for families with young children to connect as the city was growing with that particular demographic.

In this project, I explored the history of Johns Creek, GA and the ways in which Johns Creek UMC is continuing to grow with the city. I also study the history of the fellowship meal both Biblically and throughout the history of the white, upper-middle class, protestant church.

Through research, observation, survey’s, and interviews I come to the conclusion that the midweek meal not only provides a place of belonging, but it is unique in the ways in which it allows people to embody their faith through homemaking practices as well as opens the door for intergenerational interactions.

I believe that this process has helped reinforce the importance of listening and observing the seemingly insignificant. For what seems mundane; a child speaking their name and age into a microphone or a retired principal serving macaroni and cheese, often speaks volumes about the theology of a congregation.

Major Findings and Implications

The midweek meal provides a place for people to be present to one another, to share in the intimacy of a meal and to experience the fullness of God through physical and spiritual nourishment. Two pieces of the midweek gathering make the fellowship meal a distinct place of belonging: homemaking practices and intergenerational interaction. Both of these entities help develop a place within the church where a variety of skills are employed to create space where a diversity of people find belonging.

Homemaking Practices:

It is important to note that the meal does not happen without effort from staff and volunteers. Mary McClintock Fulkerson defines homemaking as “the distinctive ways the community maintains itself as a physical place, for example, maintenance and upkeep, but also as a livable place – a real homeplace where people offer each other material, emotional, and spiritual support.”3 These practices show an embodied faith. People give of their time and talents to a ministry that they recognize is important through basic homemaking practices, but practices that create a place of belonging.

Intergenerational Interaction:

While there is opportunity throughout Johns Creek UMC for multiple generations to interact, when given a choice, most will self-segregate into groups that most represent their age and stage in life. The surveys of those who do not attend the meal show that people find fellowship in Sunday School classes, small groups, and Bible studies; but none of those settings give voice to young and old like the gathering at the midweek meal. This is important because it connects a variety of people, giving voice to all and allowing avenues of revelation and growth beyond the bounds of age.

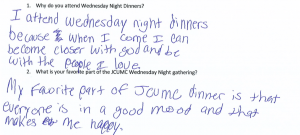

One of the best things that happened in the survey process was having a variety of responses from a wide range of participants. To collect data about the personal importance of attending Café 2:42 surveys were placed on tables throughout the gym before the meal, and the only instructions were to fill it out if one was willing to participate.

With no further instruction, children and youth participated in the survey. Their participation and willingness to further the conversation show they have found this midweek gathering to be a place where their voice matters. They have found a place where they belong and know that they have value and voice.

With no further instruction, children and youth participated in the survey. Their participation and willingness to further the conversation show they have found this midweek gathering to be a place where their voice matters. They have found a place where they belong and know that they have value and voice.

What’s Next

Having identified what makes this gathering unique, next steps would be to cultivate those practices to expand their reach. McClintock Fulkerson describes storytelling as another homemaking practice that could easily be incorporated into Café 2:42. “Storytelling, along with other genres such as aphorisms, sayings, and proverbs, is a favored form for a large number of people who express themselves through a primarily oral culture.”4 With a focus on intergenerational conversation, including children who will have oral forms of expression as their main form of communication, exploring storytelling as a community will give continue to give voice to all who participate.

Other ways to cultivate this unique place of belonging include finding ways to involve more people, giving voice to the importance and significance of homemaking practices in embodied faith and finding more ways to encourage intergenerational interactions.

There are many places that this conversation can go in the future:

• Does a congregational understanding of a fellowship meal impact their understanding of the Eucharist?

• What about fellowship meals in immigrant populations? What about fellowship meals in non-white, Protestant congregations? Fellowship meals in congregations in various socio-economic locations?

• A Korean congregation meets at Johns Creek UMC every Sunday. They have a meal following their Sunday morning worship service. What would happen if people from the English language and Korean language services joined together for a share fellowship meal?

More Food for Thought

Books that influenced this project:

Ammerman, Nancy Tatom, and Arthur Emery Farnsley. Congregation & Community. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1997.

Ayres, Jennifer R. Good Food: Grounded Practical Theology. Waco: Baylor University Press, 2013.

Berry, Wendell. Bringing It to the Table: On Farming and Food. Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint, 2009.

Block, Peter. Community: The Structure of Belonging. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 2009.

Fulkerson, Mary McClintock. Places of Redemption: Theology for a Worldly Church, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Gallagher, Nora. The Sacred Meal. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2009.

Harris, Maria. Fashion Me A People: Curriculum in the Church. Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1989.

Jung, L. Shannon. Food for Life: The Spirituality and Ethics of Eating. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2004.

Miles, Sara. Take this Bread: A Radical Conversion. London: Canterbury Press Norwich, 2012.

McKnight, John, and Peter Block. The Abundant Community: Awakening the Power of Families and Neighborhoods. San Francisco: BK, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., 2012.

Sack, Daniel. Whitebread Protestants: Food and Religion in American Culture. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

- Benjamin Zeller, Marie Dallam, Reid Neilson and Nora Rubel, ed., Religion Food and Eating in North America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014), XIX.

- Peter Block, Community: The Structure of Belonging (San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 2009). 1-2.

- Mary McClintock Fulkerson, Places of Redemption: Theology for a Worldly Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007). 127.

- Mary McClintock Fulkerson, Places of Redemption: Theology for a Worldly Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007). 134.

Save

Save