Smaller World: A Modern Day Parable

iframe src=”https://spark.adobe.com/video/6CQFQecVdrywi/embed” width=100% height=540

Light in the Electric City: Toward a Contextual Ecclesiology at First Baptist Church

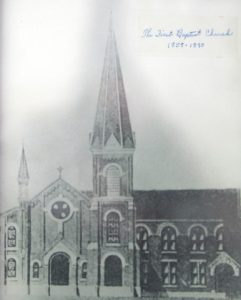

Photo 1. First Baptist Church as seen from the end of Church Street, Downtown Anderson. Photo: Ron Anderson. Used with permission.

What if that which has been unwell and consequently unwelcoming is not a person but a church? Churches, being imperfect institutions, get sick, too. There’s an entire cottage industry dedicated to diagnosing churches’ sickness and getting churches healthy and keeping churches healthy and determining what causes a church to become sick. While there is much about that work that is worthwhile and relevant, it’s not really my purpose here.

Rather, I’m looking at one of the symptoms of church sickness. In my made-up story, the reason that the person stopped being so hospitable was some kind of sickness. I’m defining sickness here as something that takes a church away from its God-given reason for existing while it turns inward in a survival mode mentality. While a person can be perfectly healthy without engaging his or her neighborhood and inviting people into the home, a church cannot be fully functioning and healthy without meaningful engagement with the world.

What The Project Isn’t

I dismissed in my project proposal some common approaches to beginning church ministries of community engagement. There may well be a place for replicating strategies that have worked in other places, but, short of drawing inspiration from other churches’ success stories as I was doing my research, I didn’t introduce those components into my work in this project. I also did not seek to develop a project that would immediately result in the development of a program that would engage the community. I acknowledge that this seems counter-intuitive, as is evidenced by those who tell me that the best approach to begin to engage the community is to formulate a new ministry by which the community is engaged.

Photo 2. Church members prepare First Baptist’s Historical Room. Photo: Anderson Independent-Mail. Used with permission.

In the parable I told earlier, I tried to paint a picture of a person who longed to be hospitable but lacked the tools to be hospitable. Jumping into a newly-developed community engagement ministry for the sake of having a program to fill that purpose would be tantamount to inviting neighbors over for dinner while lacking cooking skills, dishware, and table to make a meal possible. As the priority of hospitality gave way to the priority of survival in my parable and the tools of hospitality were consequently eschewed as unnecessary in matters of survival, priorities must be altered before the tools necessary to living out those priorities can be redeveloped.

The process I describe below may well lead to the development of a new ministry program in my church—and I hope it does—but that development will happen after the church understands who it is and who it is called to be, after it understands who its community is, what we church and community have to offer to one another, and why we are important to one another. In a residential community, this interdependence—what I described in my modern parable simply as mattering is called being neighborly. In a church, I’m calling what I have come to see as God-willed interdependence contextual ecclesiology.

The Reason for the Project

Photo 3. The sanctuary choir and orchestra during the annual Christmas musical worship. Photo: Jack Abraham. Used with permission.

While members of my church would not be likely to say that paint is more important than people, the church’s budget allocations, passion, and conversations between laypersons reveal a more immediate focus on the concerns of the congregation rather than a deep engagement with the world. At times, it appears that some view faithful service to the institutional church as being in tension with the Christian practices of hospitality, generosity, and Christian charity toward people who live in the largely poor and largely black neighborhood around the church campus. I have determined that something must change in order for the church and for me to be in faithful ministry.

Photo 4. The church sanctuary as seen from the top of the Wilmary, home of First Baptist’s housing ministry. Photo by Josh Hunt.

If change is to be meaningful and lasting, I need to more fully understand how and why the disconnect between church and community developed and what forces maintain it. In order to develop this deeper understanding, I engaged in a congregational analyis that paid careful attention to the history, demographics, congregational self-understanding, and denominational polity of my congregation. My goal was to discover the church thinking (ecclesiology) that shapes the practices of the church in relation to its neighbors. If this thinking serves as a barrier to neighbor love, it must be challenged. The goal, therefore, is to develop a contextual ecclesiology–church thinking influenced by the church’s setting–that redefines what it means to be church in this particular place and leads to greater love for neighbor. Such an ecclesiology provides the rationale for developing next steps in addressing the division between this congregation and its surrounding community.

Photo 5. The church gym prepared for the New Year’s Day meal and warm clothing give-away. Photo by Josh Hunt.

As I suggested in my parable, being healthy does not always translate into acting healthy. True wellness involves both. The process is akin to a knee replacement procedure. The surgery itself will replace deficient joint with healthy, but the patient must learn how to walk on a healthy knee again. This project is like physical therapy for a church that is emerging from sickness.

The Dilemma: Church and Community Disconnect

My congregation is seen as a wealthy, white church in a poor, black neighborhood. The church made the decision decades ago to stay in its downtown home while some other predominantly white churches moved to suburban, residential neighborhoods. The difference between congregation and immediate community represents a significant obstacle to meaningful community engagement. Though the church supports community efforts through finances, this is done at a distance, through the efforts of parterning agencies in town.

The church’s challenge is to respond to every person with the love of Christ, but the narratives that seem to be at work in the congregation must be named before the church can move toward addressing the challenge and opportunity within its own neighborhood context. What is First Baptist? What is First Baptist’s community? How did the church’s major priorities come to be separate from the community in which the church exists and more focused on the work within the church facility? Supppsing that such a separation between church and community is neither biblical nor Christian, how can the congregation rethink its priorities as church in this community?

Being a Student of the Community

I also spent hours reading the history of my adopted home. Tracing the threads of Anderson’s story from the displacement of the Cherokee in 1776, locals fighting to preserve slavery in 1860, the development of the world’s first cotton gin powered by electricity in 1897, and the rise and fall of the textile industry in the 20th and 21st Centuries informed much of my thinking about how the community came to be the place I know, as well as the centuries-old decisions that left some native Andersonians poor and some rich.

I also did a study of current demographics, property values, and crime statistics. I conducted asset mapping and interviews with boundary leaders currently serving in the neighborhoods surrounding the church. As the minister takes on the mantle of a student, he or she is not served particularly well in that roll if they pretend that they are the only person who is studying. There are people engaged in the ministry that you may be seeking to learn more about. Use them as a resource. Partner with them in their ministry.

My community research revealed that the distance between the church and the community that now surrounds it is not new. Thought the church was once very engaged in the life of its neighborhood, the neighborhood has changed but the church’s efforts to reach the neighborhood have not.

Becoming a Student of the Church

My work began with a history of the church. The time I spent pouring over Georgia Hamlet’s History of First Baptist Church proved immensely worthwhile. Beyond studying the official written history, I had conversations about the church’s history with people who have been around the church a long time. While the written history detailed church accomplishments and milestones, the oral history talked about the highs and lows that are associated with the life of any church.

I also sought to determine what the church has valued about itself and what it values now. The determination of values is crucial to the development of future ministries and also to engage community in a richer way without sacrificing a deep church identity. This exploration of the church’s theology, doctrine, and polity revealed a strong value on freedom, education, music, and worship. These values form the beginning point for community engagement.

The church’s ordinances, baptism and communion, also provide a framework for the establishment of ecclesiology. Celebrating baptism in the life of the believer, which is itself an indicator of the health of the congregation, and a challenge to the baptized person and the baptizing community to grow in the Holy Spirit is an important step in using this Baptist distinctive as a way to encourgage the congregation to venture outside the walls.

The other ordinance in Baptist life, the Lord’s Supper, is a reminder of the welcome Christ extends to anyone who would respond, regardless of race, socioeconomic status, or station in life. The way the elements are received in my church–through the distribution of small cups and pieces of bread throughout the congregation–is itself a subtle reminder that Christ equips every Christian to serve and that all Christians stand in need of receiving that which is offered.

Commending Contextual Exploration

While the development of ministries, programs, and opportunities for the church and communtiy to get to know each other are crucial, such development should take into account the complex context in which church and community mutually dwell. Ministry programs have varying levels of success in different contexts, but intentional contextual awareness can happen in every kind of congregation and can involve congregants, regardless of gifts and abilities. Contextual ecclesiology is a prerequisite to healthy ministry where congregation and community meet. Contextual ecclesiology begins with contextual exploration.

Toward Engagement

How might a church begin to engage the community from which it has been previously disconnected? The church begins the process of going out by first looking in. The church may not be able to make immediate changes in the surrounding neighborhood, but it can change its perceptions of its neighbors and its role as a church in the community.

First, the church can learn its history and the history of the community and be honest about its role, intentional or not, in perpetuating historical inequities.

Second, the church can listen for the history told by its neighbors. How do people in the surrounding neighborhood tell the history of Anderson, their neighborhood, and the relationship between the church and its neighbors?

Third, the church can reexamine its understanding of what it means to be church in its context. What is the congregation’s theological understanding of what it means to be church? Or, put another way, what is its unspoken ecclesiology? Does that theology reinforce the disconnection to the surrounding community? If it does, the congregation’s thinking about what it means to be church needs to be challenged and revised.

What’s Next?

In the absence of bishops and presbyteries to keep the congregation in line, in the context of a system of calling ministerial staff that sometimes makes prophetic teaching and preaching difficult for fear of losing one’s job, the family at First Baptist must continue to teach our people how to read and interpret scripture for themselves. Church staff must train congregants to be sensitive to the leadership of the Holy Spirit. Leaders must encourage Christians to engage in cross-generational conversations, in cross-racial conversations, in cross-cultural conversations. Institutional memory has a way of maintaining a history that is heavily-edited in a way that benefits the institution.

The First Baptist observed today did not suddenly become what it is; it has been born and born again for nearly two centuries. Worship style, affirmation of women in ministry, theology, doctrine, scriptural interpretation, denominational identity, and community engagement have been shaped as much by the people who have “lost” and left the church as much as it has been by the people who have “won” and stayed. The outcome of some of these once-divisive issues—previously the result of an effort to create a compromise and initiate a fragile peace—has now solidified into an identity.

Baptist ecclesiology is not always formed in ideal circumstances or with ideal motives, but even with denominational and congregational eccentricities, I remain a proud Baptist and feel called called by God to this place and time. I count it a blessing to serve and serve among the people called First Baptist Church, for I know that as I serve, teach, preach, and study, I am undertaking the sacred work of interpreting the ecclesiology of this church today and helping author what he hopes will be an increasingly contextual ecclesiology of this church tomorrow.

Save

Save

Select Bibliography