In August of 2014 an unarmed black teenager named Michael Brown was shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. The Brown shooting happened on the heels of the choking death of Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York, at the hands of another white police officer. In November of that same year, after a grand jury chose not to indict Wilson of Brown’s death, protests—both violent and non-violent—broke out in Ferguson and around the United States.

A police car burns on the street after a grand jury returned no indictment in the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri November 24, 2014. REUTERS/Jim Young

I was ten years into ordained ministry with an affluent, largely white, urban Episcopal parish in Atlanta when the Ferguson protests happened. I was convicted by the idea that something needed to be said from the pulpit and terrified to be the one to do it. Early in December of that year, I had a text conversation with another priest, a trusted friend who is an African American woman serving as chaplain at an historically black university. To avoid alienating my congregation, I asked whether I could focus on the sanctity of all human lives rather than making the sermon—and the ensuing conversation– about race. She answered me very gently and compassionately, saying,

I guess I wonder about those people in your congregation who are conscious — both whites and blacks who understand well the sanctity of the phrase “black lives matter.” I wonder how they will feel to hear you say instead, “all lives matter.” Will it isolate them in a time when we already feel especially isolated?… I haven’t read a sermon yet that acknowledges the black people who were present there. In fact, in all of the efforts to “do the right thing” by challenging white people, [white preachers have] done a thing that black people have struggled with for centuries — they ignored the black people in their midst. By failing to care/acknowledge the deep emotions being carried by the black people in their midst, they essentially rendered their black congregants invisible.

My friend’s words touched me profoundly. Since that day, and through more social upheaval in our country, I have become interested in the challenge of preaching difficult messages of social justice, particularly racial equality, to affluent white congregations. This is not a new phenomenon. Preachers of all stripes have been railing against the various evils of their societies with varying degrees of success since Jesus began the movement. However, in a time of declining church attendance the pressure to preach in such a way that we draw people in rather than run them off is having significant effects in how many of us view the critical time we spend in the pulpit.

Our Christian scriptures call us into works of love, mercy, and justice. God’s voice instructs the people through the prophet Isaiah that in order to heal their transgressions before God, they must, “learn to do good; seek justice, rescue the oppressed, defend the orphan, plead for the widow (Isa. 1.17).” Our Proverbs instruct us to “Speak out for those who cannot speak, for the rights of all the destitute. Speak out, judge righteously, defend the rights of the poor and needy (Prov.31.8-9).” The instruction to care for and defend our brothers and sisters extends throughout the Hebrew Bible and yet, when Jesus himself instructs in the synagogue in Nazareth “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor,” he is run out of the town by an angry mob (Luke 4.18-21).

The mandate to preach and practice justice is a strong and ever-present theme in the New Testament but it is not universally popular. Jesus often finds himself on the wrong side of authorities who fight against his message of justice and mercy, of love over law, of abundance over scarcity. That fight that eventually leads to his torture and execution. Even with this strong tradition in scripture and even with the witness of Christ before us, the practice of preaching social justice and human rights is still not universally accepted in the Christian tradition, a fact which causes angst in preachers that want to turn that tide.

Walter Bruggemann, in his classic The Prophetic Imagination, says, “The task of prophetic ministry is to nurture, nourish, and evoke a consciousness and perception alternative to the consciousness and perception of the dominant culture around us.”1 Bruggemann sees critique of the culture around us as part and parcel to the preaching and pastoral life and that critique is precisely what makes the prophetic act so difficult. He offers, though, that the prophetic ministry has two parts: the critique of culture and the cutting away of brokenness but also the energizing of God’s people and refilling them with the hope they need to accomplish the work.2

This small body of work is one piece of an ongoing exploration of this topic in my professional life. In the midst of the research for this work, I answered a vocational call to another urban cardinal parish, also affluent, more politically cautious and less diverse than the one I had served in Atlanta. More than ever, I needed to find some new tools for helping my new congregation move toward an appreciation of hearing social justice messages from the pulpit rather than fearing or disdaining those messages.

In this project, I read and listened to a dozen sermons by mainline white Christian preachers and picked four to illustrate my observations. I wanted to compare preachers of the Civil Rights Movement that were able to move their congregations toward greater understanding of the Gospel call to love and serve everyone to those in the more recent Black Lives Matter movement that were seeking to do the same thing.

“Civil Rights March on Washington” by Archives Foundation is licensed under CC BY 2.0-28B-73-10

07638_2003_001

The Preachers

The Civil Rights Movement

In the 1950’s and 1960’s and even into the 1970’s, the Civil Rights Movement was sweeping across the United States. The primary goal of the Movement was to end racial segregation and discrimination against African-Americans in the United States and to promote equality among the races.

The Reverend William Sloane Coffin, New York, New York

William Sloane Coffin was a white preacher and pastor who managed to build a successful career and powerful voice by preaching against social ills beginning in the 1960’s. As an ordained Presbyterian minister, he believed that social justice and social activism were central to his duties as a cleric.3

In an essay about Coffin’s preaching preparation, Leonora Tubbs Tisdale notes that “When Coffin preaches on a social issue, it is clear that he has done his homework and done it well. The result is that he is able to articulate the opposing point of view clearly and accurately. Even if you disagree with him, you know he has entertained and considered other points of view along the way.”4 Coffin did not avoid difficult, charged topics in his preaching. But he did not tackle these difficult subjects lightly. His sermons were well researched to the point that it was hard to argue against them.

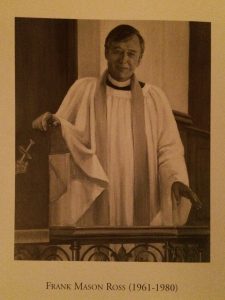

The Reverend Frank Mason Ross Margaret Ellis Langford, All Saints’ Episcopal Church: To Seek, To Celebrate, To Serve, n.d., 53.

The Reverend Frank Ross, Atlanta, Georgia

Meanwhile, during the same era of Civil Rights in the United States Frank Mason Ross was the rector of All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Atlanta, Georgia, from 1961-1980. A history of the parish says that “Ross was courageous, outspoken, honest, and he inspired extreme reactions, one way or another, in most parishioners.”5

In a sermon preached on July 5, 1964, the Sunday following the enactment of the Civil Rights Act, Ross preached boldly about his own understanding of how the Act would strike directly—and positively in his estimation—at the heart of “customs and traditions of long-standing”.6 Ross uses two thoughtful tools in this sermon that speak to his love and care of his congregation as well as his passion for the Act and its implications.

First, Ross aligns himself with his congregation. By using the word “we” throughout, by reminding that he, too was “raised in the South—and not the New South of Atlanta either but in the coastal, rural areas of Eastern North Carolina,” Ross reminds the congregation that he is one of them, not an outsider critically looking in.7

The second tool he uses is to name the fears of his congregants. He knows why the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is frightening to them and he names it. He uses these fears as a launching point to help them understand why they must continue to move forward, both in society and in the Kingdom of God, reminding them in the end that Christ died to free us from death and from fear of the unknown.

The Black Lives Matter Movement

Following the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner in 2014, a grassroots movement known as the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement came together to ensure that in the eyes of the law and in the eyes of the general public, the lives of African-American men and women would be as valued as the lives of other human beings in the United States. Blacklivesmatter.com defines the movement as “a chapter-based national organization working for the validity of Black life. We are working to (re)build the Black liberation movement.”8

The Reverend Casey Kloehn, Monterrey, California

The Reverend Casey Kloehn’s Blog, “Casey and the Sunshine”

In December of 2014, as BLM was beginning to gain momentum as a social media movement, Casey Kloehn was a seminarian and candidate for orders in the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America living in Davis, California, serving as the Lutheran Campus Minister for University of California Davis. In a sermon that she preached for a local congregation, she used homiletical tools very similar to those used by preachers mentioned above during the Civil Rights Movement.

Kloehn is a young woman and a daughter of the congregation and uses both of these facts to her advantage. She reminds the congregation that she “sits” among them and places herself within the collective history of the church. She reminds them that they are known. She also reminds them that the parish’s history is rooted in Gospel-based justice work.9 From this place of familiarity, Kloehn is able to push harder with the congregation on the realities she understands as counter to that Gospel-based work.

The Reverend Stephen Muncie, Brooklyn Heights, New York

Stephen Muncie is recently retired from 12 years as the rector of Grace Episcopal Church, a nearly 170 year old historic parish in Brooklyn. The December 2014 rise of the Black Lives Matter Movement coincided with the parish’s annual foundation celebration, two seemingly disparate facts that Muncie wove together in his sermon for the day.10

Muncie begins with the story of the parish’s founding 166 years before, weaving in the parish history with the nations history, reminding the congregation of milestones of the Mexican-American War, the cholera epidemic, Civil War, abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage. From here, Muncie moves into the Gospel for the day, Mark 1.1-8, John the Baptist crying out in the wilderness.11

In his sermon, Muncie literally practices what he is preaching, while he is preaching it. He becomes the prophetic voice in the wilderness, crying out about those things to come. Muncie’s sermon was given to a congregation that he had served as rector for 10 years, and whom he knew well. Muncie appropriately capitalized on both the relationship and the forward movement of the parish to challenge the congregation into new visions of how they would serve the people and the Gospel in their next chapter.

Four Tools for the Preacher’s Toolbox

Through the study of these sermons and through the study of several preaching texts and commentaries, I have identified four “tools” that are useful to me as I continue to develop my own prophetic voice in the pulpit.

P.T. Forsyth: “Take home anew the Gospel”

P.T. Forsyth, congregationalist pastor and theologian, in the 1907 Beecher Lecture at Yale University, says “[the preacher] is not a mere reporter, not a mere lecturer, on sacred things. He is not merely illuminative, he is augmentative. His work is not to enlighten simply, but to empower and enhance. Men [sic] as they leave him should be not only clearer but greater, not only surer but stronger, not only interested, not only instructed not only affected, affected, but fed and increased“.12

Self-differentiated preachers are often able to understand that changing the hearts of the people, to leave them clearer, stronger, instructed and increased is a goal to strive toward, though not a measure of self-worth or professional prowess.

Kelly Miller Smith: Pre-Proclamation

Smith offers what he calls the “‘pre-proclamation’ function of the preacher.”13 Perhaps the most complicated part of Smith’s strategy, “pre-proclamation” calls for the preacher to be involved in constant social justice and social crisis work. A preacher who is involved in the work and also well-studied in the issues around the causes she is involved in will, according to Smith, find better reception for her words by the time of the homiletical event. “Communication begins not when the text and sermon title are announced,” posits Smith, “but when the minister functions in the community in relation to critical social circumstances and shows social sensitivity prior to proclamation.”14

Tony Campolo and Michael Battle: Modeling truth before preaching

Tony Campolo and Michael Battle lean into this idea that theology of liberation and reconciliation must be lived before it can be preached. “We must first model truth before speaking about it,” they offer, “We must worship truth before doing theology.”15 For Battle and Campolo, this argument is centered largely on how white congregations can approach the process of becoming congregations of true racial reconciling and healing, but the theory stands for the preacher of social justice as well. A preacher who is modeling practices of social justice for and with the congregation might find much more traction when it comes time to speak a difficult word from the pulpit. “The model,” Battle and Campolo posit, “becomes a prophetic framework for understanding the sacred.”16

Leonora Tubbs Tisdale: Speaking Truth in Love

Tisdale reminds her readers about “Speaking Truth in Love.”17 Building trust between preacher and community helps the preacher gain traction when it is time to bring difficult messages of social justice. A preacher who comes only with words of challenge without first establishing a rapport of love and trust with the people he serves will find sermons falling on deaf ears. Casey Kloehn’s sermon to the church of her youth has many elements of speaking truth to love in the way she connects with the parish as one of their own, raised up to both do the work and to bring the word.

On a personal note, while researching and writing for this work, I stumbled into an

almost embarrassingly obvious reality that to my dismay did not appear in any of the texts I was reading: this work is not to be done alone. At various times, colleagues and ordained friends have encouraged my ministry and lovingly criticized it, lifted me up and took me to task. My advisers tell me the truth in kindness, even when it is hard to hear. The value of trusted advisers from outside the parish, be they friends, professional colleagues or mentors, cannot be overemphasized. Those who are isolated, by choice or by circumstance, have higher rates of burnout and failure. If we believe in the social justice call of the Gospel, as pastors, our advisers should be as diverse a group as we can muster so that we can constantly be attentive to the full spectrum of human need and constantly be refilling our wells with new information for how to lead in grace, strength, and humility.

1 Walter Brueggemann, Inscribing the Text: Sermons and Prayers of Walter Brueggemann (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2004), 20.

2 Ibid., 60.

3 Marc Charney, “Rev. William Sloane Coffin Dies at 81; Fought for Civil Rights and Against a War,” The New York Times, April 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/13/us/rev-william-sloane-coffin-dies-at-81-fought-for-civil-rights-and-against.html.

4 Leonora Tubbs Tisdale, Prophetic Preaching: A Pastoral Approach (Louisville, Ky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 59.

5 Margaret Ellis Langford, All Saints’ Episcopal Church: To Seek, To Celebrate, To Serve, n.d., 53.

6 Frank M. Ross, “Sermon on the Sixth Sunday after Trinity” July 5, 1964.

7 Ibid.

8 “Black Lives Matter: Freedom & Justice for All Black Lives,” accessed August 16, 2016, http://blacklivesmatter.com.

9 Kloehn, Casey. “What Shall I Cry?” Casey and the Sunshine, December 8, 2014. http://caseyandthesunshine.blogspot.com/2014/12/what-shall-i-cry.html.

10 Stephen Muncie, “Our Deadly, Immoral Wilderness,” accessed March 2, 2017, http://www.gracebrooklyn.org/serve/sermons/our-deadly-immoral-wilderness/.

11 Ibid.

12 William H. Willimon, Pastor: A Reader for Ordained Ministry (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2002), 137.

13 Kelly Miller Smith, Social Crisis Preaching:The Lyman Beecher Lectures (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1984), 80.

14 Ibid.

15 Tony Campolo and Michael Battle, The Church Enslaved: A Spirituality of Racial Reconciliation (Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress Press, 2005), 126.

16 Ibid.

17 Tisdale, Prophetic Preaching, 42.

Save

Save

Save