A BLACK NARRATIVE PULPIT

The Narrative Lectionary as a tool for Christian Transformation

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. “Sunday in Little Rock, Ark., 1935.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed March 24, 2017. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-f89b-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

I love the Black Church and I cherish being part of a uniquely American tradition layered with rich religious, social and cultural textures. I love worship in the Black Church, whether it is in a highly liturgical Episcopal congregation or a two-stepping, fire-baptized Church of God in Christ. I love Black preaching and hold in high regard the task and the sacred responsibility that comes with its work. I love the Black Church, but in recent years I have developed a bit of a lover’s quarrel with its relatively newfound comfort with biblical illiteracy and lack of Christian transformation, especially as it rubs against its historic identity as a center for Black justice and liberation. I have developed a deep frustration in the last decade of my professional ministry with the low levels of biblical literacy within the Black Church—by this I mean a parishioner’s intimacy with and broad understanding of the stories of the God as revealed in the Scriptures of the Christian Tradition. More recently, my frustration has led me to fear that the staggeringly low levels of biblical literacy are fundamentally hindering the Black Church from being the place of prophetic transformation God desires.

I serve as the Senior Pastor of Christian Fellowship Congregational Church (United Church Christ). It is one of the oldest Congregational churches in continuous operation in the City of San Diego. It was organized on the second Sunday in November 1886 when the Rev. J.W. Harwood first conducted services. The church was founded as the Second Congregational Church and members of the First Congregational Church contributed liberally to the establishing of the new church. The congregation predates the establishment of the United Church of Christ and its predecessor denominations the Congregational-Christian Church and the Evangelical-Reformed Church, which merged in the 1957 to create the United Church of Christ. In 1947 the congregation, then known as Logan Heights Congregational Church, called its first African American minister, the

I serve as the Senior Pastor of Christian Fellowship Congregational Church (United Church Christ). It is one of the oldest Congregational churches in continuous operation in the City of San Diego. It was organized on the second Sunday in November 1886 when the Rev. J.W. Harwood first conducted services. The church was founded as the Second Congregational Church and members of the First Congregational Church contributed liberally to the establishing of the new church. The congregation predates the establishment of the United Church of Christ and its predecessor denominations the Congregational-Christian Church and the Evangelical-Reformed Church, which merged in the 1957 to create the United Church of Christ. In 1947 the congregation, then known as Logan Heights Congregational Church, called its first African American minister, the

Reverend E. Major Shavers, to serve as co-pastor the congregation—and soon began to take on the identity of its local community, filled with educated, middle-class African-Americans, many being educators, military and business professionals which still make up the base of the congregation today. Christian Fellowship presents itself as a well-educated, middle-class, Black Bible-based church that has grown over the course of this project to be accepting and affirming of human diversity and sexual difference, gender equality and worker justice, and the practice of environmental stewardship. Particularly in the last year of this project, the church has come to embrace a deep sense of call to be a community that cares for the immigrant, the marginalized and oppressed and other “blues bodies.”[1]

I was called to Christian Fellowship (UCC) in 2010. While I had served on several ministerial staffs in the Commonwealth of Virginia, North Carolina and most recently at the Riverside Church in the City of New York, it was the first time that I would serve as the primary preaching pastor of any local congregation. I was both excited and intimidated by the new vocational calling. In nearly all of the settings where I had served previously, the guide for preaching and worship was the Revised Common Lectionary (RCL). The RCL was a preaching schedule that I had become familiar with over the course of my ministry, and was the lectionary of choice for my two predecessors in ministry at Christian Fellowship, the Pastor Emeritus, the Reverend Dr. James Hester Hargett, and his successor. In the early months of my pastorate I invited the leadership of our congregation into a series of conversations on worship, specifically the role, if any at all, a lectionary, would play in this new season of ministry.

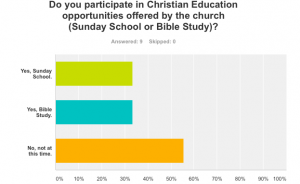

After three years of following the Revised Common Lectionary (RCL) at Christian Fellowship (UCC), I began to sense that my congregation’s overall biblical literary needed further development and sought a new tool to guide the congregation in that effort. Over the course of those years there was little enthusiasm for Wednesday Night Bible Study, and the only Adult Sunday School class that existed consisted of a small group of seniors.

Excitement around the study of Scripture was non-existent in the life Christian Fellowship (UCC), and there was little sign of Christian transformation, particularly as social witness, within the congregation. I felt that the surest way to build excitement, grow the congregation’s biblical literary and acts of transformation would be through preaching and worship. I remember early conversations with colleagues in ministry when I first began exploring the use of other lectionaries in worship. Many suggested that I not venture into a new lectionary, especially having completed a full cycle of the RCL. They suggested that I use build upon the previous year’s work in the development of new sermons–these would be the easy years of ministry, they said—because so much exegetical work had already been completed. But I searched for something far more challenging for a congregation who had heard several cycles of the RCL, and lacked in biblical literacy.

In the spring of 2013 while attending a denominational gathering I was introduced to the Narrative Lectionary by a UCC colleague from Kiel, Wisconsin, the Reverend Ashley Nolte. Rev. Nolte had been in her congregation for three years before beginning to experimenting with the Narrative Lectionary in 2012. In using the Narrative Lectionary she began to experience not only excitement in the challenge of narrative preaching, but she was also discovering that her congregation’s knowledge of the biblical story was improving as the long broad narratives were shared from week to week. Reverend Nolte directed to me a weekly resource where that week’s texts came alive in scholarly debate and conversation.

The Narrative Lectionary was developed by Rolf Jacobson and Craig Koester of Luther Theological Seminary in St. Paul Minnesota. It was conceived by Jacobson at a denominational gathering (2010) where he contemplated in a breakout session with local church pastors, “why churches don’t preach the Old Testament in big brush strokes from Labor Day through Christmas, preach one gospel from Christmas through Easter, and preach early church stories and Acts until Pentecost.”[2] The idea quickly became a liturgical experiment when Dan Smith, an ordained minister of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), recruited a handful ELCA churches who agreed to put the idea into practice in their local congregation if Jacobson were to create it.

After the denominational gathering, word about the lectionary experiment, first conceived as a nine-month project to address the “perceived biblical illiteracy in the ELCA,” spread quickly and at its launch, in the Fall of 2010, Koester and Jacobson had approximately 40 preachers and congregations ready to embrace the new idea.[3] The Narrative Lectionary, at present, has grown to include congregations from many different Protestant denominations within the country and around the globe. Jacobson and Koester created the Narrative Lectionary with the aims of exposing “people to preaching on the major stories” and reinforcing through worship “the importance of the biblical story.”[4] The Narrative Lectionary is structured as a four-year lectionary.[5] It consists of a preaching text and an alternative reading to complement the preaching text.

Link to video featuring Prof. Rolf Jacobson speaking on the Narrative Lectionary [6]

When we explored the idea of using the Narrative Lectionary in the summer of 2013 at Christian Fellowship (UCC), there was great resistance. Several encouraged me to abandon the lectionary idea completely and just preach whatever the Lord laid on my heart—as did earlier preachers and guest preachers who filled the pulpit when it was vacant. This group of leaders felt that my sermons would be more spirited if this were the approach to sermon development and formation. The idea of knowing the biblical text months in advanced troubled many who felt that this kind of advanced knowing signified that it was not a “fresh,” “in season,” or “right now” Word. Others, especially those who had came from the United Methodist Church, Presbyterian Church USA, and Evangelical Lutheran Church in America pushed for the Revised Common Lectionary (RCL), the one that had been used primarily by my two predecessors in ministry. Many of them cited strong reasons to use the RCL, chief among them was being able to be in dialogue on Monday morning or Sunday evening with friends from around the country and compare notes, or rather determine which preacher did a better job with the text. Others who wanted the RCL cited very poor reasons, like wanting to keep an expensive color bulletin that the denomination provided featuring reflections on the RCL in word and art. Through educational moments in business and ministry meetings, along with notes in the bulletin and continuous conversation grounded in the language of being on the “Narrative Lectionary journey” the church has come to appreciate the unique qualities of our having established a Black Narrative Pulpit.

“Many preachers feel that a lectionary preaching schedule may be too confining, but experience with it proves something different…the Spirit was guiding those who prepared the lectionary…” [7]

—The Reverend Dr. Samuel DeWitt Proctor

A Black Narrative Pulpit offers imaginative biblical preaching in the Black Church, addressing the issue of biblical literacy, and inciting Christian transformation among those in the pews using the Narrative Lectionary as its primary lectionary preaching tool. A Black Narrative Pulpit offers transformative preaching in the Black Church when it utilizes the power of story telling as a tool for shaping belief patterns and behaviors, recognizing that since the earliest periods of time, across cultures and across disciplines, humans have used the power of story to change lives. A Black Narrative Pulpit offers

soul-stirring preaching in the Black Church when it promotes the use of story and narrative, particularly the story of God as revealed in Scripture, as a starting point for answering humanity’s deep questions of meaning and value. A Black Narrative Pulpit offers prophetic preaching in the Black Church when it addresses the concerns of biblical illiteracy by preaching the major stories of God, sequentially moving through our present canon. A Black Narrative Pulpit offers systematized Narrative Lectionary preaching in the Black Church, a lectionary designed to address broad concerns of biblical illiteracy in the mainline church, to establish a communities where empowered and transformed disciples of Jesus Christ learn how to live transformed in the world, and also transform the world in which they live. A Black Narrative Pulpit offers imaginative biblical preaching in the Black Church, addressing the issue of biblical literacy, and inciting Christian transformation among those in the pews.

This doctoral project seeks to examine the use of the Narrative Lectionary in a Black Church, Christian Fellowship (UCC), to determine if its consistent use contributes to greater biblical literacy and supports Christian transformation within Christian Fellowship (UCC). The use of the Narrative Lectionary has grown significantly over the years to include many different denominational traditions and congregations throughout the world—but has yet to be significantly embraced by the Black Church. This project seeks to broaden the reach of the Narrative Lectionary by examining a Black Church as it employs this new lectionary tool.

The project’s major findings make clear that lectionaries are beneficial tools for Christian formation and education—whether it be sequential lectionaries that move a congregation from creation accounts in Genesis to invitations to bear witness in Revelation, or thematic lectionaries like the African American Lectionary, which takes into account the cultural calendar of the Black Church. I argue that the benefits of using a lectionary far outweigh any resistance to it, even the kind of resistance that gave birth to the “Invisible Institution”—a resistance I argue is far more complicated than mere resistance to textual limits and a desire for Spiritual freedom, but a resistance to the visible institution that tried, and even presently works, to diminish Black life and deny Black liberation and freedom.[8] In my work I argue that the resistance Black Churches feel toward the textual limits of the lectionary remind those in the Black Church of the real experiences of black powerlessness, when worship in the visible institution was controlled and maintained under White supervision, and that there is legitimate resistance on the part of the Black Church to White religious authorities, culturally and contextually distant from the Black Church recommending texts. Notwithstanding, and in light of Dr. Proctor’s work, I suggest that Black Churches in particular resist the resistance, and test the Spirit. This project has led me to believe that those who regularly use a lectionary are more equipped to provide a well-balanced biblical diet for those in the pews than those who find lectionaries to be too confining.[9]

My research and findings have led me to conclude that establishing a Black Narrative Pulpit, a space of imaginative, prophetic biblical preaching in the Black Church, using the Narrative Lectionary, addressing the issue of biblical literacy, and inciting Christian transformation among those in the pews, has strengthened worship, improved biblical literacy, and incited Christian transformation at Christian Fellowship (UCC). Establishing a Black Narrative Pulpit opened the way for this community to creatively embody a new world shaped by the biblical story revealed in the Christian Scriptures; a story that has helped this church live out its unique calling to be a culturally relevant, biblical, story-shaped community of faith, justice, liberation and holy love. Using ethnographic research tools members have noted their growth and their improved fluency with the Hebrew Bible and New Testament. The development and excitement of new Sunday School classes, and increased attendance at Bible Study bears out the fact that the Narrative Lectionary has contributed to greater biblical literacy at Christian Fellowship (UCC). The most significant testimony of transformation in the life of this Black Church is that of becoming a Black Church that welcomes and affirms persons who identify as LGBTQI and those who are differently-abled.[10]

The Reverend Dr. Kelly Brown Douglass suggests that the radical welcome of “blues bodies” into the fullness of the Black Church embodies the very nature of being a transformative Black Church: a community with a “morally active commitment to advance the life, freedom, and dignity” of all Black bodies.[11] Greater literacy of the biblical text, and the experience of hearing long expanded stories of Jesus and who he identified with–many within the congregation were transformed in the hearing of stories from members who identify at the margin, to the end that an almost unanimous decision was made to embraced a radical theology inclusiveness, affirmation and welcome. In doing so the church has become the first Black UCC Church in the nation to hold official designations by the denomination as both an 1) Open and Affirming congregation; welcoming and affirming of persons who are LGBTQI, and 2) Accessible to All congregation; affirming, celebrating and creating space for persons who are differently-abled.[12] Developing a practical understanding of a theology of limits has proved helpful in understanding disability theology.[13] In this theology we are to understand disablism not as an exceptional instance that rubs against the norms of what it means to be fully human, but as one of the many limits that humanity has, or will have, in their lifetime. A theology of limits moves disablism from a place of pity and empathy to a place where norms become more fluid and the disabled are no longer expected to be “treated” or “rehabilitated” into an idealized normative ability.

The Black Narrative Pulpit at Christian Fellowship (UCC) has contributed to greater biblical literacy, and Christian transformation. The congregation has developed an intimacy with the biblical text that they did not have before. The congregation thinks critically about the texts and is unafraid of questioning, challenging texts, or outright disagreeing with a biblical text. As a result of establishing a Narrative Black Pulpit at Christian Fellowship (UCC), the church has gained comfort with the broad arc of the biblical narrative. This has been proven through surveys, conversations, and other feedback loops in which members recall the broad connections across the biblical canon showing not only familiarity with the text but a sense of intimacy with the story of God and biblical themes. The congregation has come to know, understand the text, and long to embody the kind of world that the text invites them to create, which is the most significant sign of transformation.

The Black Narrative Pulpit at Christian Fellowship (UCC) has contributed to greater biblical literacy, and Christian transformation. The congregation has developed an intimacy with the biblical text that they did not have before. The congregation thinks critically about the texts and is unafraid of questioning, challenging texts, or outright disagreeing with a biblical text. As a result of establishing a Narrative Black Pulpit at Christian Fellowship (UCC), the church has gained comfort with the broad arc of the biblical narrative. This has been proven through surveys, conversations, and other feedback loops in which members recall the broad connections across the biblical canon showing not only familiarity with the text but a sense of intimacy with the story of God and biblical themes. The congregation has come to know, understand the text, and long to embody the kind of world that the text invites them to create, which is the most significant sign of transformation.

Further research on the topic should seek to determine if the findings experienced at Christian Fellowship (UCC), are similarly experienced in other Black Narrative Pulpits throughout the country, or could be experienced in other Black Churches unfamiliar with the Narrative Lectionary.

Sermons from a Black Narrative Pulpit

Sermon Title: Finding Favor (1 Samuel 1:9-11, 19-20; 2:1-10)

Sermon Title: Politics of New Covenant (Jeremiah 36 1-8. 21-23, 27-28 and 31:31-34)

Sermon Title: A Reason to Worship and Praise (Luke 9:28-40)

Sermon Title: Thirsty (John 7:37-52)

Sermon Title: Untitled (John 9)

Sermon Title: Delayed but not Denied (John 11:1-44)

Sermon Title: The Drama of Decision Making (John 18:28-40)

Sermon Title: The Irony of a Stone Seat (John 19:1-16a)

Resurrection Sunday (John 20:1-18)

[1] Kelly Brown Douglas, Black Bodies and the Black Church: A Blues Slant (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 73-78.

[2] Steve Thorngate, “What’s the Text: Alternatives to Common Lectionary,” Christian Century 130, no. 22, 22.

[3] Timothy Andrew Letzeke, “Lectionaries and Little Narratives: Children of the Revised Common Lectionary,” Liturgy 29, no. 4 (2014): 29, accessed January 24, 2017, doi: 10.1080/0458063X.2014.922004.

[4] Ibid., 29.

[5] See Appendices 1-4 of DMin Thesis for Narrative Lectionary Years 1-4

[6] What is the Narrative Lectionary, Vimeo video, 3:17, Rolf Jacobson speaking on the Narrative Lectionary on May 2, 2016, posted by Daniel Mauer, May 2, 2016, https://vimeo.com/164988503

[7] Samuel DeWitt Proctor, The Certain Sound of the Trumpet: Crafting a Sermon of Authority (Valley Forge: Judson Press, 1994), 37-38. Kindle Edition.

[8] E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro Church in America, (New York: Schocken Books, 1963), 16.

[9] See Appendix 5 of DMin Thesis for a Timeline of Lectionary Development

[10] See Horace Griffin, Their Own Received Them Not: African American Lesbians and Gays in Black Churches (Cleveland: Pilgrim Press, 2006) for the most current scholarship on Queer Theology and the Black Church.

[11]Kelly Brown Douglas, Black Bodies And The Black Church: A Blues Slant (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), xiii. For more on “embodied Black theology” see for example Eboni Marshall Turman, Toward a Womanist Ethic of Incarnation: Black Bodies, the Black Church, and the Council of Chalcedon (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

[12] See Nancy Eiesland, The Disabled God: Toward A Liberatory Theology of Disability (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994) where she calls for radical inclusion and affirmation of persons who live with disability in to the full life the Church, and the creation of liberating images, ideas and values of persons who are differently-abled that view them as whole persons, not broken and in need of fixing.

[13] Deborah Creamer in Disability and Christian Theology (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009),64, suggests that humanity’s “limits need not be seen as negative but rather…an important part of being human.” For more on a theology of limits and debate on normative ability within disability theology see John Swinton who suggests that disability should be understood as a “social experience that is shaped and formed by the particular context in which a person’s perceived difference is experienced” in his article “Disability, Ableism and Disablism,” in The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Practical Theology (Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 444.

Save

Save