The Problem: A Lack of Eschatological Vision

Nearly fifty years ago, in 1971, John Lennon issued his now famous sociological and theological dare to “imagine there’s no heaven.”1 During the intervening decades, however, most Americans have not stepped up to Lennon’s challenge. As recent as 2014, the vast majority of Americans continued to express a persistent belief in heaven.2 Even among those who are “unaffiliated” with any specific religion, which includes atheists and agnostics, more than one-third say they believe in the existence of heaven.3 It would seem that the American cultural imagination is far from abandoning its curiosity with heaven in particular, and eschatology more generally. To the contrary, despite the dawning of “the secular age,” there has been an apparent resurgence of interest in the possibilities that exist beyond the horizon of our present reality.

The church would presumably be well-equipped to respond to this resurgent interest concerning the future of the world. Both the Old and New Testaments convey a vision of promise and judgment, a vision of a new heaven and new earth in which the shalom of God reigns over a restored creation. The ancient creeds of the Church speak of Jesus as the one who “will come again to judge the living and the dead and his kingdom will have no end.” These scriptural and liturgical affirmations are most succinctly stated in the ancient mysterium fidei (mystery of faith): Christ has died. Christ is risen. Christ will come again. It is evident that the Church, both in its reading of the Bible and its practice of public worship, possesses the necessary language and tools to respond to the growing confusion concerning eschatology and our future hope.

Yet despite the depth and sophistication of scriptural and liturgical traditions, many Christian congregations seem ill-equipped to join the cultural conversation about what exists beyond the horizons of our present reality. This lack of eschatological vision within many Christian denominations can be understood, in part, as a reaction against eschatological views espoused within certain segments of the American evangelical movement of the late twentieth century.4 More broadly, the diminishment of eschatological vision can be attributed to the general cultural process of secularization, most especially the loss of transcendence within the modern worldview.5 As one commentator has observed, “the contemporary imagination is held captive in the closed circle of extant reality.”6 The church is not immune from this lack of transcendent imagination. In large part, the church has “accepted the terms of the demystified world secularism boasts,” and has thus “failed to address the secular age with a compelling narrative.”7

The Project: First Peter as a Model for Preaching Eschatology

Congregational Analysis

The first phase of my project included an in-depth analysis of my congregational context. at Good Shepherd Episcopal Church in Tequesta, Florida. Good Shepherd is a program-sized congregation that is located in the incorporated village of Tequesta, an affluent, suburban community situated in northern Palm Beach County. The membership of Good Shepherd is predominantly white, which is reflective of our surrounding community, and is comprised of both older retirees and younger families. Currently, the average Sunday attendance is approximately 290, which is significantly higher during the winter months, due to the influx of seasonal residents. Good Shepherd is a member of the Episcopal Church and worldwide Anglican Communion, which means our common life is rooted in the liturgical and sacramental practicesassociated with the Book of Common Prayer and Anglican hymnody.

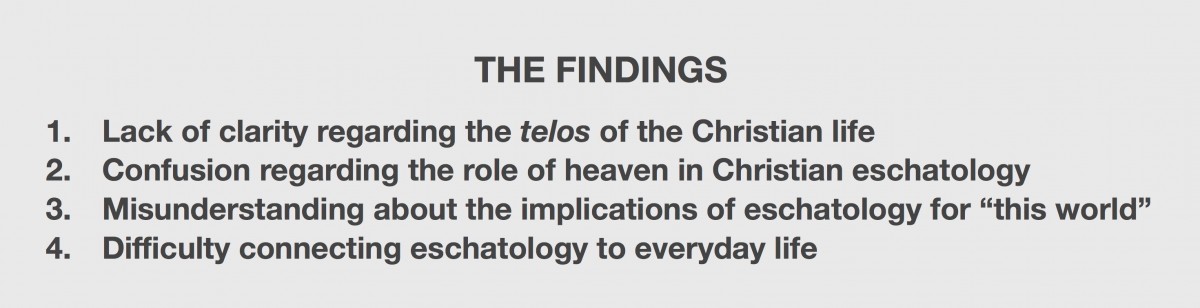

The ethnographic study of Good Shepherd included multiple means of data collection. First, I conducted two successive Bible study groups; the first focused on the theme of biblical eschatological in general, while the second focused specifically on the eschatology of First Peter. Secondly, I gathered a diverse representation of church members to serve as focus groups, which discussed specific questions related to the topic of eschatology. Third, I taught a four-week adult education class on the topic of heaven and the Christian hope. Finally, I conducted a congregational survey, which attempted to capture general attitudes and assumptions regarding the field of eschatology. The ethnographic study, which was conducted over a period of approximately six months, resulted in the identification of the following four areas of deficiency with regard to our understanding and application of the Christian hope for the future.

Exegesis of First Peter

The second phase of my project included an exegetical analysis of the Epistle of First Peter. I selected First Peter because it seeks to address the unique challenges related to living the Christian life faithfully in a non-Christian society. The vision of Christian life as espoused in the Epistle of First Peter is deeply eschatological and this eschatological focus informs the theological and ethical vision of the letter. My exegetical analysis of First Peter was specifically focused on the ways in which the theological framework of the epistle might serve as model for addressing the deficiencies noted above.

The second phase of my project included an exegetical analysis of the Epistle of First Peter. I selected First Peter because it seeks to address the unique challenges related to living the Christian life faithfully in a non-Christian society. The vision of Christian life as espoused in the Epistle of First Peter is deeply eschatological and this eschatological focus informs the theological and ethical vision of the letter. My exegetical analysis of First Peter was specifically focused on the ways in which the theological framework of the epistle might serve as model for addressing the deficiencies noted above.

The Telos of the Christian Life – The congregational analysis revealed that a majority of respondents expressed a general sense of hopefulness for the future, but also an inability to articulate precisely what they are hoping for. This absence of a defined telos or goal toward which we are striving inevitably leads to a sense of futility and purposelessness. First Peter speaks confidently about the ultimate telos of the Christian life and our place in the larger story of God’s redemptive plan for the world. Peter tells his community, “you are receiving the outcome (telos) of your faith, the salvation of your soul” (1:9). The telos or goal of the Christian life, according to Peter, is the experience of salvation. The present reality of salvation is evidenced by the experience of “new birth” made accessible through baptism, which “now saves you” (3:21). However, there remains a future culmination that will be accomplished when Jesus Christ is revealed (1:7). For Peter, the theological virtue that sustains the life of the believer “in-between” the present experience of salvation and its future consummation is hope. These insights from First Peter provide an anecdote to the deficient clarity regarding the telos of the Christian life and our place in the larger narrative of God’s vision for the world. First Peter articulates an eschatological vision that enables the Christian to escape the “crisis of immanence” and embrace “a living hope” that is both a present reality and our future inheritance. However, this eschatological vision only makes sense if we first expand and deepen our understanding of the nature of heaven.

Heaven: Not Just a Destination – The telos of the Christian life as described in First Peter is closely associated with the concept of heaven. According to Eugene Boring, within the theological framework of First Peter, “the Christian does not “go up” at death to receive [this inheritance], but goes forward in history to meet it at the eschatological consummation.”8 Consequently, it can be said that the eschatological vision of First Peter includes an understanding of heaven that is less a destination to which we go when we die and more a dimension from which Jesus is revealed and the promised inheritance is received in “the last time” (en kairo eschato). In one sense, the Christian community is already living in “the last times,” the period which included the first appearing or manifestation of Jesus (1:20). And yet, there is a second, future manifestation that is yet to come (5:4). It is between these two great revelatory moments that the Christian lives and waits. The Christian is waiting not for a final escape away from this world, but for the final revelation of Jesus from heaven, which will signal the consummation of the new life and hope already experienced in the present reality of this world.

Eschatological Implications for this World – What difference does the Christian hope for the future make in the present? We have discussed the central theme of hope, which pervades the letter of First Peter. This vision of hope is intimately connected to the experience joy. For Peter, one the most important implications of eschatology for this world is the experience of exceedingly great joy! However, the experience of abundant joy described in First Peter is all the more remarkable because it is encountered even in the midst of suffering. Central to Peter’s theology of suffering is the conviction that the experience of suffering is not tangential to the Christian life, but is an imitation of and participation in the experience of Jesus (4:1). The theological “glue” that holds together the experience of suffering-for-others and that of exceedingly great joy is the eschatological vision that Peter describes, a vision, which as we have seen, is not focused on an escape from this world, but a “living hope” that is for this world. Thus, the eschatological vision of First Peter affirms the present reality of new life and vibrant hope. This promise of life and hope are experienced as the Christian participates in both the resurrection of Jesus from the dead (1:3) and his sufferings in the flesh (4:1). In midst of suffering, the faith of a believer is “tested” and “purified” just as gold is refined by the intense heat of the fire. It is clear that the eschatology of First Peter has profound implications for life in this world and, therefore, has the potential to significantly shape and transform the daily lives of those who have chosen to follow Jesus.

Living Eschatologically in the Present – Having established that the eschatological vision of First Peter is not “other-worldly,” but has important implications for this world, we now turn our attention to the specific ways eschatology influences the daily life of the Christian. The eschatology of First Peter “does not refer to the future in such a way that it can be isolated from the past and present.”9 In other words, the meaning of the Christian life is only understood it light of the larger narrative of God’s plan for the world. Therefore, eschatology is ultimately “a matter of living in a meaningful history, life in a story-shaped world of which God is the author, not speculation about the future.”10 To live eschatologically in the present is to understand one’s life as part of God’s story, a story that will lead us and all creation to the “completion or fulfillment of all things” (4:7). Throughout the letter of First Peter, this connection between eschatology and ethics is consistently communal in nature. The communal call to holiness entails having pure hearts (1:22), doing good deeds (1:17), doing what is right (2:14-15), being subordinate and respectful of order (3:1ff), non-retaliation (3:9), pursuing peace (3:11), selflessness (5:2-4), humility (5:5), and gentleness (3:16). The characteristics of a holy life are not disconnected moral injunctions, but rather together define the Christian community as the eschatological people of God. The ultimate Christian hope for the future, the anticipated telos of the Christian life, empowers the believer to live a life of holiness in the present in the context of daily life. We now turn to practice of preaching with an eschatological voice.

The Proposal: Trajectories for Preaching

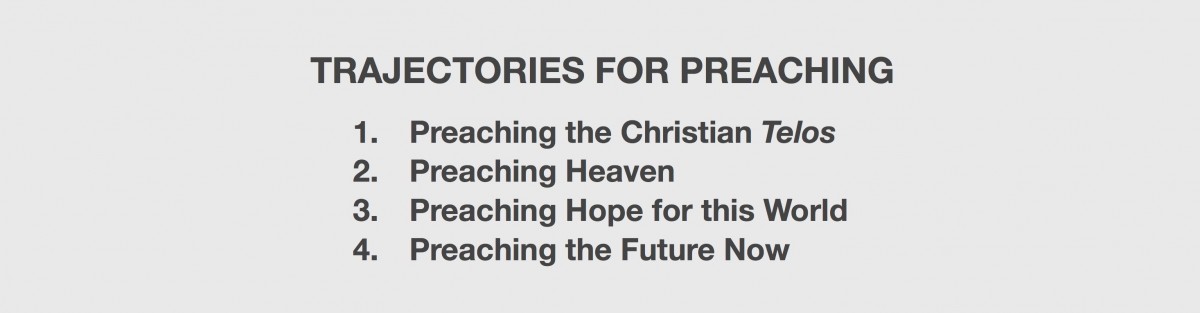

The final component of my project includes four proposed trajectories for preaching. These four trajectories are meant to provide a possible path forward as preacher seeks to reclaim their eschatological voice and empower their congregations to think eschatologically. Using the insights gleaned from both the congregational analysis and exegetical study of First Peter, I offer the following four trajectories for preaching:

Trajectory1: Preaching the Christian Telos – The first trajectory relates to the proclamation of the telos of the Christian life, the ultimate hope toward which are moving and for which we are laboring. As Boring reminds us, “human life itself is forward-looking, is stretched out on a temporal line that moves toward the future. Human life is constituted by this movement; to have something to ‘look forward to’ is to have something to live for. To have no tomorrow is to be robbed of today; to be given a future is to be given a present.”11 The proclamation of the Christian telos is exemplified by the introductory section of First Peter, in which the Christian community is reminded of the rebirth they have received as well as the corresponding hope, inheritance, and salvation that is theirs through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead (1:3-5). The outward and visible sign of the gift of new birth is the waters of baptism and the resultant experience of forgiveness and renewal. However, the experience of new life given through baptism in the present will one day reach its future completion and fulfillment “in the last time” when Jesus Christ is revealed (1:7). It is only the promise of the future consummation that ultimately gives meaning and substance to the experience hope in the present. This teleological dimension of preaching is best expressed by Tom Long who states, “eschatological preaching affirms that life under the providence of God has a shape, and that shape is end-stressed; what happens in the middle is finally defined by the end.”12 The preacher is called to proclaim boldly the good news that the ordinary, unceasing procession of time is not without meaning or purpose, but is rather moving toward a telos, a time in which we will see and experience the completion and fulfillment of God’s vision for the world.

Trajectory2: Preaching Heaven – The second trajectory for preaching directs our attention to our assumptions regarding the nature of heaven. The effective preaching of the Christian telos must also address the deficiency of imagination regarding the role of heaven in our eschatological vision. As we explored above, the majority of participants in the congregational analysis conceived of heaven almost exclusively as a location away from this world, the ultimate destination for righteous souls. According to Richard Bauckham and Trevor Hart, throughout history “Christian hope has consistently been understood as hope for human fulfillment in another world (‘heaven’) rather than as hope for the eternal future of this world in which we live.”13 Contemporary spiritual writer and pastor, Brian McLaren, argues that we have turned the announcement of God’s glorious vision for the future of this world into “an evacuation plan” out of this world.14 The reclamation of our eschatological voice must include a reimagining of our conceptualizations of heaven. The challenge of the postmodern preacher is to break through the centuries-old Platonic worldview that envisions an otherworldly, disembodied “heaven” and to reimagine a future that is firmly rooted in the promises inaugurated through the incarnation and resurrection of Jesus, a future that offers hope for this world.

Trajectory3: Preaching Hope for this World – The preaching of the Christian telos and the reimagining of heaven as an integral part of God’s holistic plan of salvation naturally leads us to our third trajectory for preaching – the articulation of the implications of eschatology for this world. Because we have failed to clearly express the telos of the Christian life and have correspondingly perpetuated a diminished, other-worldly conception of heaven, the contemporary church lacks the capacity to imagine an eschatology that has meaning and transformative power in the present. The central element of First Peter’s eschatological vision for this world is hope. As Boring observes, the “understanding of biblical hope in First Peter is a sharp contrast to the cultural use of the word “hope” as a nice way of saying that something might happen, but probably won’t. In biblical theology, “hope” is the not-yet-reality by which one already lives: a small child a day before Christmas, an engaged couple a week before the wedding, a prisoner a year before release.”15 To preach hope for this world is to “participate in the promise that the fullness of God’s shalom flows into the present, drawing it to consummation. Eschatological preaching brings the finished work of God to bear on the unfinished world, summoning it to completion.”16 The challenge we face as preachers is to mitigate against the influence of the dominant other-worldly conception of our Christian eschatological hope and to reaffirm that, even in the midst of suffering, the vision of God’s future for the world is a source of “exceedingly great joy.”

Trajectory 4: Preaching the Future Now – Finally, perhaps the most significant trajectory for preaching is the urgent need to proclaim the capacity of eschatology to shape and transform our daily lives as followers of Jesus. The ability to see the present “in the light of hope” means that we understand every facet of lives as finding its true meaning within the larger story of God’s plan for the world. Our marriages and families; our professions and vocational journeys; our sorrows and joys; our successes and failures – are all caught up in the grand vision of God’s eschatological hope for the world. This is a message our contemporary world desperately needs to hear. In the context of the Christian community, we most fully embody of the present reality of this eschatological vision through our worship and witness. The gathered Christian community is called to be the eschatological people of God. Through our worship, we bring the mundane and ordinary elements of our lives – money for offering plate, bread for the sacramental meal, canned goods for the local food pantry – and yet these representations of our lives are caught up in the larger vision of hope for the world; our worship becomes a proleptic sign of the completion and fulfillment (telos) that one day will be revealed. Our identity as God’s eschatological people is also manifested through our witness in the world. The new identity bestowed upon the church through the resurrection was given that we might “proclaim the mighty works of God” (1 Peter 2:9). The call to faithful witness is most notably associated with Peter’s exhortation to “always be ready to make your defense to anyone who demands from you an accounting for the hope that is in you” (3:15).

Next Steps: Continuing the Journey

This project has provided me with important information about the current state of eschatological thinking and vision within my own congregational context. Based on these findings, I have proposed a particular set of trajectories for preaching. Using these trajectories, I am working to create a sermon series for the season of Easter, which can be used during for the Revised Common Lectionary, Year A. The Easter season is an especially appropriate time of the church year to explore themes of resurrection and eschatology. For it is the resurrection of Jesus that most keenly reminds us that “in the end there is a new beginning.”17

1 John Lennon, “Imagine,” John Lennon-Imagine Lyrics, accessed January 12, 2018, www.metrolyrics.com/imagine-lyrics-john-lennon.html.

2 “America’s Changing Religious Landscape,” Pew Research Center, May 12, 2015, http://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/.

3 Pew Research Center, “America’s Changing Religious Landscape.”

4 See Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins, Left Behind: A Novel of the Earth’s Last Days (Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, 1995), 1-32.

5 David Lose, Preaching at the Crossroads: How the World – and our Preaching – Is Changing (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2013), 50.

6 David M. Greenhaw, “Preaching and eschatology: opening a new world in preaching.” Journal for Preachers 12, no. 3 (1989): 3.

7 Lose, Preaching at the Crossroads, 61.

8 Eugene M. Boring, 1 Peter, Abingdon New Testament Commentaries (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1999), 62.

10 Boring, 1 Peter, 65.

11 Boring, 1 Peter, 64

12 Thomas G. Long, Preaching from Memory to Hope, (Westminster John Knox Press, 2009), 126.

13 Richard Bauckham and Trevor Hart, Hope against Hope: Christian Eschatology at the Turn of the Millennium (Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans, 1999), 129.

14 Brian McLaren, Why Did Jesus, Moses, the Buddha, and Mohammed Cross the Road?: Christian Identity in a Multi-Faith World (New York: Jericho Books, 2013), 211.

16 Long, Preaching Between Memory and Hope, 125.

17 Jürgen Moltmann, The Coming of God: Christian Eschatology (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004), ix.