Most of my life, I have lived in large cities where people live in anonymity. I have lived in Buffalo, Indianapolis, Mobile, Bremerhaven, Colorado Springs, Atlanta, and Montgomery. In my experience of living in large cities, I had no lifelong connections with people other than my family. Not staying in one place for more than a few years did not allow for long-term, shared history, and life-long relationships to form. In 2008, I was appointed to serve Chatom United Methodist Church in rural southwest Alabama. Chatom is a small town with a population of 1,237 and one traffic light.

I quickly discovered, mostly by error, that many people in Chatom were related by blood or marriage or had lifelong friendships with, or a lifelong feud with, residents of this small town. I noticed quickly too that African-Americans and White Americans did not socialize together. In the other places I lived, it was commonplace to find people of different races dining together, sitting together at sporting events, and worshiping together. In Chatom, however, the opposite was true. The races were separated geographically, socially, and economically. I wondered how people of both races who knew one another their entire lives, had a shared history, and remained here to work and raise families did not interact.

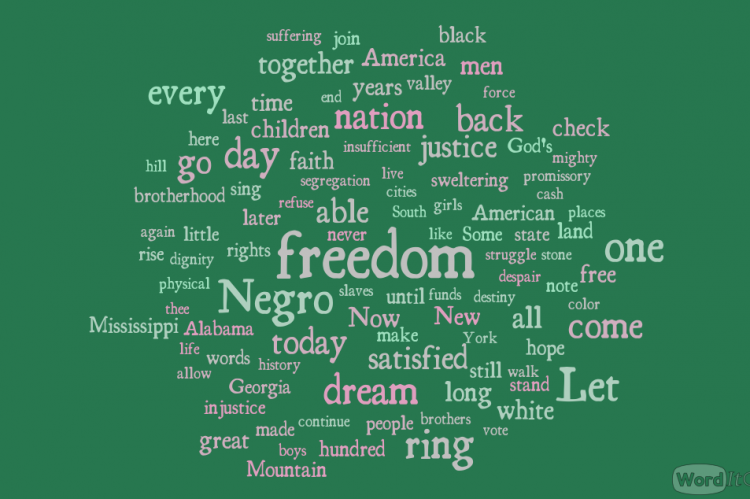

In 2016 with a fiery Presidential Election in full swing and movements around the country such as Black Lives Matter, I noticed an increase in racist comments, emails, and social media from some residents. I wondered what it would take for people with a life-long acquaintance to come together as a diverse group to share their stories, their experiences, and work together to make our community a Beloved Community, a vision of society shared by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.-a community that would work together towards mutual goals of diversity and acceptance to make Chatom a beautiful place for all children to be accepted, to grow, and learn.

I felt led to do something tangible to combat the angry, hate-filled, and racist rhetoric that swirled within our community and in my congregation. As a White pastor, I knew I had been called to make a difference and to speak out, act, and model the behavior of Jesus who I claimed to follow. I had preached numerous sermons about racial injustice and had conveyed a message of inclusiveness for all God’s people. In our current climate of unrest, violence, and anger, I believed that I had to do more. I had to take some tangible action. I needed to do something in our community that would begin to address the issue of racism.

The Christian Methodist Episcopal Church and the United Methodist Church I serve began worshiping together occasionally, and our joint worship was the talk of our small town. For weeks after our first joint service, I was approached on numerous occasions at the local grocery store, the post office, and the bank with back-handed comments about worshiping with the “Black church.” As followers of Christ, we are called to love one another, bear one another’ burdens, and to be patient. Spewing hate and inciting racial divide and anger is in direct conflict with the teachings of Christ. At the very least, our actions got people thinking and talking about a new time of fellowship. The year was 2016, and there had not been any previous combined services with both Blacks and Whites in attendance. We had taken one small step in the right direction, and I was hoping we had initiated some change.

I wondered what would be the impact of a small focus group of racially diverse people who came together to share in a discussion on race relations in rural Alabama? To use the term racial reconciliation for this study implies there is equality between the races when the reality in the United States today refutes such a claim. There can be no reconciliation until there is equal justice in this country. The road we needed to travel to achieve an environment of healing and acceptance was rocky and fraught with pitfalls. But, there would not be any closing of this great chasm between the races until there is honest communication. We had to start somewhere, and we needed to start soon.

My goal was to address the issues of racism and build a community between the two churches (one with a White congregation and the other with a Black congregation) with hopes of fostering positive relationships between Blacks and Whites. As the focus group comprised church members; I hoped that Christian hospitality would provide a welcoming space for all participants. As believers in Jesus Christ, we cannot fully share in the Body unless we become unified in our diversity. The prophet Micah encourages us in our walk with God, “This is what the Lord requires of you: Do justice, love kindness, and walk humbly with your God.”[1] We must recognize one another in our otherness, our woundedness, and our differences as children of God; otherwise, we will not experience full oneness with God. The ideal result would be to build Beloved Community, a new community, where diverse people seek justice, love, and nurture each other as children of God. In Reggie L. Williams’ book, Bonhoeffer’s Black Jesus, he offers this observation on racism, “From the hidden perspective it is apparent that racism prohibits authentic Christian discipleship.” [2] Williams is correct; it is not possible to be an authentic Christian if you are a racist. In his book, Then the Whisper Put on Flesh, author, Brian K. Blount discusses the Gospel of John and what it reveals to us about genuine Christian community. Blount echoes Williams statement by writing the following observation about the community called Christian. A Christian community and witness is one of love, equality, and care for one another. Christians are not called to exclude individuals by race, ethnicity, or illness. Christians are to live a life of inclusiveness. We are called to love and nurture one another in genuine Christian fellowship.

A diverse group of people from both the Black and White churches came together to share in a dialogue about race. I had hoped that since the group was made up of active members from both churches, that there would be a shared sense of Christian fellowship and community. Unfortunately, I was proven wrong.

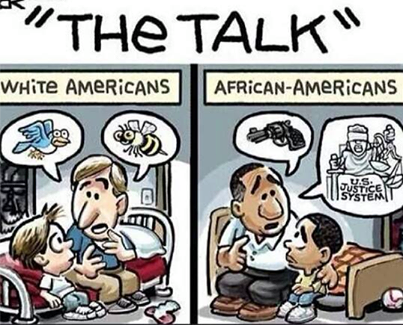

My observation made of the White participants in our initial meeting was that they seemed confused and bewildered by the concept of racism. Their body language and facial expressions indicated extreme discomfort and fear. While it was observed that individuals from both the Black and White group were fidgety and nervous, the White’s level of discomfort and stress appeared to be higher than that of the Black participants. It occurred to me through observation that, since African-Americans operate daily in a White dominated society, they were used to being uncomfortable around White people. Whites may feel guilt, shame, and sorrow at how they have treated their African-American brothers and sisters and therefore participating in a social face-to-face situation is awkward. In Sue’s book, he shares the following explanation of why race talk is uncomfortable for Whites; “Avoiding race talk is to avoid the acknowledgment of power and privilege held by many Whites over their brothers and sisters of color.”[3] I became concerned that we had done more harm than good. The task at hand was becoming more complex.

After the first meeting, several White members approached me privately and began to share their concerns. “There is no such thing as White privilege; there is affirmative action which has given advantages to African-Americans,” one person stated. “Black people are too sensitive about race, and they play the race card to their advantage;” “Maybe if more Blacks held down jobs and were productive rather than relying on welfare, they would get more respect.” Another told me, “We have had a Black President, and that means there is no more racial inequality in our country-we are a post-racial country.” This same person then stated, “I consider myself colorblind and not a racist.” One individual informed me that she believed that, “Whites are now the victims of reserve discrimination.” Whites do not ever have to consider their race, while Blacks must always be aware of theirs. Since none of them had ever participated in what they considered overt individual acts of racism, therefore, they were not racists and had done nothing that contributed to the problem—if indeed there really was a problem. They believed that they held no responsibility for supporting a system that sustains institutional and systemic racism. To remain silent in the face of racial injustice makes us guilty of indifference in the face of suffering and that is counter intuitive to the teachings of Jesus Christ. Jim Wallis shares his observation, “Just as surely as blacks suffer in a white society because they are black, whites benefit because they are white. And if whites have profited from a racist system, we must try to change it.” [4] One of the White members expressed concern because he believed that reverse discrimination and anti-white bias is more of an issue in our country than anything currently experienced by Blacks. His observation is refuted in an article by Samuel Sommers and Michael Norton, “From life expectancy to school discipline to mortgage rejection to police use of force, outcomes for white Americans tend to be-in the aggregate-better than outcomes for black Americans, often substantially so.” [5] In addition to their racist remarks, they were resisting the attempts to bring a diverse group together. It was time to rethink the entire project.

A new strategy was envisioned. The Education of Whites about racism and its effects was necessary before any productive and meaningful dialogue could take place between Blacks and Whites. I began to do research, looking for books and articles that would assist me in educating Whites on the issues that arise from racism and how it has systematically kept people of color from achieving equality in our society.

To begin to have a conversation about race; the White participants needed to learn about the reality of racism in America. The first question was where to begin? The clearest answer, was, a working definition of race. The definition we came up with was, race is not a biological factor; it is a social, cultural, and economic classification of individuals to benefit one group. Racism exists when one race has distinct advantages in education, housing, and employment opportunities. It became evident how imperative it was for White people to take a serious look at the reprehensible history of oppressing Nonwhites solely for the economic benefit of Whites—for the White members of the new focus group to realize how our American system of oppression has caused the division, injustice, and the lack of opportunity for our African-American brothers and sisters in Christ.

I decided to research books and articles addressing the issues of White privilege and racism written by White American authors. The book I chose for the new focus group was Jim Wallis’ America’s Original Sin. Wallis’ book addresses racism in a non-threatening way for Whites, and yet, conveys the horror of racism for Blacks. In addition, Wallis covers not only racism in the book but addresses White privilege as well. My research led me to a helpful resource that Sojourners offers. It is a six-part discussion guide with suggested Scripture readings, thought-provoking discussion questions, and prayers readily available for download. There are several videos available on YouTube with Jim Wallis talking about racism and White privilege I used with the group.

I introduced Whites to concepts demonstrating how their treatment is different from that of African-Americans. The new group admitted that the concepts introduced were new to them and they would consider and share their reflections at the following meeting. Their reflections were honest, and several stated, that thinking about the new views on racism had been disconcerting.

The concept of White Privilege was alien to the White focus group. Each participant admitted that until recently they had never even encountered the term. Several members added that they had never entertained the idea that they received differential treatment because of the color of their skin. In Derald Wing Sue’s book, Race Talk and The Conspiracy of Silence, he indicates the following reasons why white’s may wish to avoid the topic of privilege, “Confronting White privilege in race talk means entertaining the possibility that meritocracy is a myth, that Whites did not attain their positions in life solely through their own efforts, that they have benefited from the historical and current racial arrangements and practices of society, and that they have been advantaged in society to the detriment of people of color.”[6] It was an unsettling new awareness, and it provoked some soul-searching dialogue and discovery. After a lengthy discussion, the group all agreed that; despite the civil rights movement that began in the 1960’s to address discrimination endured by people of color, five decades later our society is still hierarchical, exclusionary, and stubbornly resistant to change.

Because of the early and revealing conversations where the former White members expressed their negative views, I decided to formulate an initial survey with the purpose of moving the new group to think differently about race and racism. One of the first inquiries asked on the survey was: “Have you ever been overlooked while standing in a checkout line because of the color of your skin?” Other questions included: “When you stay at a hotel do the complimentary shampoos and toiletries work with the texture of your hair?”; “Has an employer or anyone else ever assumed that you got your job/position or into a particular school because of affirmative action?”; “Have you ever been profiled, followed, pulled over, or harassed by store security or law enforcement because of your race?” “While in school did your textbooks reflect people of color and their accomplishments and contributions to the world?”; “Has anyone ever assumed that because of the color of your skin, you could sing, dance, had rhythm, or were good at sports?”; “Have you ever given any thought to the fact that you inherit and benefit automatically from a world of White privilege?”; “What is White privilege?” “Please provide your definition of racism:”; and “Do you believe that racism is an issue in our country today?”

A careful assessment of answers given to the above questions before and at the completion of the focus group provided an assessment tool to see if people’s thinking changed after participating in this project. In addition, at the closing of the study, I added these additional questions: “Did participating in this project give you a new understanding of what it means to be a person of color in our country?”; Other questions included: “How has your participation in the group prompted difference in conversations you have with others regarding race and racism?”; “Are you more in tune with how people of color get treated in our community?”;“Has your definition of racism changed since participating in this study?” “How has participation in this study changed how you think about the history of racial oppression in our country?” The above questions are just some of the ways to measure the effects of the study.

To change people’s thinking long-term is beyond the scope of this project. My goal was to instruct the white group on the history of racism in the United States—the effects of racism on not only African-Americans but the negative impact it has on White-Americans as well. It is impossible for Whites to begin to understand the Black experience if they have never thought about racism from an African-American’s point of view. Since the new white group was made up of professional, and well-respected individuals, who held leadership positions in Chatom, we hoped that others would follow suit. I was encouraged by their willingness to be a part of the group, as, their participation would positively impact the project in the future. I hope that their positive influence on other white members will result in attracting more people to consider learning about the issues of racism.

My experience with the failure of the first focus group led me to the conclusion that until White Americans recognize and begin to understand the African-American reality in our society there will not be productive dialogue. In my second attempt with the White American focus group, I found that by learning, listening, and considering the experience of Black Americans that the White group began to change their perceptions and began to think in a new way. The new group was ready after the six-week study to meet with their African-American brothers and sisters to hear their stories and were open to meaningful dialogue.

My project is an ongoing one and on Easter Sunday, 2018, for the third year the White Methodist and the Black Methodist worshiped together, participated in the Sacrament of Holy Communion, and shared a meal after the service. The presence of first time attendees of both races encouraged me. Our joint service has been receiving positive feedback and the positive impact of our service is evidenced in the increased participation. It is my hope that over time more people will come together, share stories, fellowship, and form a more inclusive community.

- Micah 6:8 (New Revised Standard Version).

- Reggie L. Williams, Bonhoeffer’s Black Jesus: Harlem Renaissance Theology and An Ethic of Resistance (Waco, Baylor University Press, 2014), 56

- Derald Wing Sue, Race Talk and the Conspiracy of Silence: Understanding and Facilitating Difficult Dialogues On Race, (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc, 2015, 24.

- Jim Wallis, America’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America, (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2016), 49.

- Samuel Sommers and Michael Norton, “White people think racism is getting worse. Against white people.” The Washington Post, July 21, https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2016/07/21/white-people-think-racism-is-getting-worse-against-white-people/?utm_term=.cf9f4550766

- Sue, Race Talk, 32.

Bibliography

Sommers, Samuel and Norton, Michael, “White people think racism is getting worse. Against white people.” The Washington Post, July 21, https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2016/07/21/white-people-think-racism-is-getting-worse-against-white-people/?utm_term=.cf9f4550766

Sue, Derald Wing. Race Talk and The Conspiracy of Silence: Understanding And Facilitating Difficult Dialogues On Race. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2015.

Wallis, Jim, and Bryan Stevenson. America’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America. Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2016.

Williams, Reggie L. Bonhoeffer’s Black Jesus: Harlem Renaissance Theology and An Ethic of Resistance. Waco, Baylor University Press, 2014.

As of April 2021, how is the focus group going?