Synopsis of the Project

Saint Mark United Methodist Church and Lutheran Church of the Redeemer in Atlanta, Georgia collaborated together with the new Atlanta/Fulton County Pre-Arrest Diversion pilot program to offer space and resources for participants of pre-arrest diversion to rest, have basic needs of food, cleanliness, clothing, and rest met while beginning the triage process of lining up services and treatment.

Congregational Background

Saint Mark United Methodist Church is an urban ministry setting in Midtown Atlanta with a current membership of approximately 1500 and a weekly attendance of around 200-300 people between two services each Sunday. The church is comprised mostly of White progressive thinking (and voting) people and is also comprised of approximately 80% Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer/Questioning (LGBTQ) people.

Due to its urban location in Atlanta and sense of identity based on welcoming marginalized people, Saint Mark regularly has homeless people attending services, meals, and other programming opportunities. Several decades ago, members of Saint Mark formed a weekly breakfast “club” on Saturday mornings and supper “club” on Tuesday evenings for our homeless congregants. A clothing closet was added as well as a foot care clinic, and weekly office hours were scheduled for direct assistance.

Homeless outreach does have its problems. The church property routinely has homeless people camping out at night. This is typically not a problem until trash and drug and sex paraphernalia start to accumulate where people are sleeping, and urination and defecation create an unbearable odor at all of the building entry points. This activity typically comes in waves and has intensified because of the recent closing of the largest homeless shelter in the city of Atlanta, the Atlanta Taskforce on the Homeless, located less than a mile south of Saint Mark UMC at the corner of Peachtree and Pine Street.[1] The cycle begins when three or four people start sleeping on the church grounds at night and sometimes during the day. The office and clergy staff often gets to know many of them by name and sometimes even offer money in exchange for help with odd jobs around the facility. After a while, additional people join them at night and that is when trash, drug paraphernalia and bodily waste accumulate. The staff then asks the campers to leave the premises. Things escalate when the police have to be called to move people along, and eventually, an overnight security company gets hired for a period of time to break the habit and keep the property clean. When the police are involved, thee is typically an arrest made for any number of charges such as trespassing or public intoxication. For years, church staff and members have looked for alternatives to arrest if the police have to be called, and the advent of Pre-Arrest Diversion has given hope for more meaningful remedies to crimes associated with homelessness and poverty.

Why Pre-Arrest Diversion?

(Video produced by the Solutions Not Punishment (SNaP) Coalition)

Pre-Arrest Diversion (PAD) is a program by which individuals detained by police for certain crimes can be diverted into services or treatment, rather than be processed into the criminal justice system. For two years, a taskforce appointed by Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed initially in response to the specific issue of prostitution expanded their work to see whether recidivism around crimes of poverty might be addressed in a new way.

All of these elements in inclusion, LGBTQ members, homeless outreach, and a heart for social justice have made Saint Mark an ideal faith partner with PAD to develop a partnership that is mutually beneficial and that can be replicated with other congregations and faith communities across the city as the PAD program expands. With a clear and shared vision, PAD is able to help Saint Mark increase involvement around homelessness in a new way and engage in practices that help people who are homeless transition back to lives where they can sustain themselves.

Recidivism in Atlanta

The issue of recidivism has become an increasingly detrimental problem in urban areas across the United States, and particularly in Atlanta. In a report generated by the office of Fulton County (Georgia) District Attorney Paul Howard, a study done by the Andrew Young School of Policy Studies at Georgia State University was referenced that analyzed recidivism in Fulton County between the summer of 2011 and the spring of 2014. The study showed that 80% of offenders who offended in 2011 reoffended sometime before spring 2014.[2] That is almost double the national recidivism rate of 43%.[3]

The design team of the Pre-Arrest Diversion initiative (PAD) set out to collect additional data and information that could be used to clarify the scope and size of the problem of recidivism related to crimes of extreme poverty. An analysis of current trends related to service calls and arrests related to quality of life, prostitution, and narcotics charges was published by the primary investigators of PAD to gain specific data of the problem in Atlanta. The data for this report was provided by the Atlanta Police Department, the Fulton County District Attorney, and the Atlanta City Public Defender office and published in a document entitled “Diversion Eligibility Data Walk,”[5] which further demonstrated the need for pre-arrest diversion services. The data investigators analyzed all of the 83,298 calls for service (911 calls) made from July 1, 2015, through July 31, 2016. In the Data Walk document, it was determined that of those calls, 20% of them, or 16,659, were for PAD-related offenses having to do with quality of life, prostitution, and/or narcotics. The top three PAD-related complaints were Suspicious Person (6,772 calls), Criminal Trespass (3,994 calls), and Illegal Alcohol/Drugs (1,177 calls). Of those calls, the top five causes for arrest were: possession of a controlled substance (1,484 arrests made), drinking in public (731 arrests made), pedestrian violations (such as jay-walking) (570 arrests made), defecating/urinating in public (236 arrests made), and criminal trespass (221 arrests made). Of the possession of controlled substance arrests, 77% were for possession of less than one ounce of marijuana. The top three PAD-related arrest categories for Atlanta Police Department beat 505, which is the beat that Saint Mark UMC is physically located in, were drinking in public (29 %), possession of a controlled substance (34%), and pedestrian violations (37%). The identified race of the people in over 80% of arrests in all categories were African-American. [6]

This report was both illuminating and shocking. It gave a clearer sense of the closeness of the problem to the physical campus of Saint Mark UMC, what is going on in our own neighborhood, as well as insight into the crimes of poverty in which our homeless congregants were engaging. The statistics that were presented in the report and in subsequent organizational meetings also showed that most of the arrests for transgender prostitution activity that happens in the city of Atlanta occurs within a two block radius of Saint Mark’s property. Many of the trans-women who get arrested for prostitution are homeless, jobless, and have been kicked out of their families.[7] The prostitution they engage in is referred to by PAD as “survival sex” because it is the only thing they are able to do to make money to survive. Given the proximity of the problem to Saint Mark UMC, I encouraged the leadership of our congregation to be a part of the solution.

Supporting Pre-Arrest Diversion as a Faith Community

The PAD design team put together community workshops to gain allies and partners and to help community members envision and implement PAD in an effective way. The team specifically wanted clergy and faith communities involved in the organization and implementation of PAD, and reached out to a number of clergy for participation. My congregation, Saint Mark United Methodist Church, was identified as a potential partner because of its involvement in a number of social justice initiatives and I began attending the design team meetings to seek out how my congregation could be helpful. After attending several more meetings, as well as hosting a meeting on our campus, it was clear that the desire for clergy and congregations to be involved was present, but it was unclear to everyone specifically what that would look like beyond merely offering moral support. I met with Moki Macias, the newly hired PAD Executive Director, who had helped convene the first conversations about diversion practices in Atlanta. We further explored the question of faith community participation in PAD, and from those conversations, the focus of this research emerged.

Evolution of the Project

The purpose of this project was to answer the question of how clergy and congregations can be involved with pre-arrest diversion efforts by mobilizing Saint Mark United Methodist Church and other churches in the pilot district to provide meaningful support, collaboration, and resources to the Atlanta PAD program.

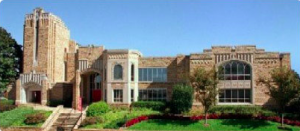

Lutheran Church of the Redeemer

Saint Mark UMC

(In the map above, Saint Mark UMC is located on the right at the corner of 5th and Peachtree Streets and Lutheran Church of the Redeemer is located on the left at the corner of 4th and Peachtree Streets)

Saint Mark UMC collaborated with Lutheran Church of the Redeemer, our next door neighbor, and PAD to form a Memorandum of Understanding outlining terms for our churches to create and maintain a space stocked with resources for use by the PAD social workers, referred to as “Care Navigators.” The Care Navigators bring participants diverted from arrest to the church to take care of immediate basic needs such as food, shower, and rest and to begin the triage process for getting services and treatment. The space was named Care PAD and is physically located at Lutheran Church of the Redeemer, with Saint Mark collaborating on keeping the space stocked with clothing, towels, hygiene kits, food, and other items needed.

Implementation and Outcomes

The success of Saint Mark’s collaboration with PAD and Lutheran Church of the Redeemer can be defined in three dimensions: results (the accomplishment of the task/goal), process (how the work was developed and monitored), and relationship (how people experienced each other while doing the work and their sense of connection to the work).[8] In the beginning, it was unclear to PAD specifically how congregations could be helpful despite the articulated desire to have faith communities be a part of the work. The response that we collectively developed was the Care PAD space, which has been used in an effective way with diversion participants. This was the result of our process and relationships and is a functional success.

Our process involved taking the time to prioritize numerous meetings, phone calls, email exchanges, and brainstorming. The process was tedious at times, but the slow pace allowed all of the parties to ask thoughtful questions, receive accurate answers, and problem solve through the scenarios that had not been considered before. With clarity around the task of the churches, an action plan was created to realize the shared goal. This accomplished the process dimension of success.

Relationships began developing through my consistent presence at the organizational meetings, and from the openness that the PAD Design Team had in partnering with my congregation and any other congregations willing to help. Our conversations with PAD and Redeemer involved a shared sense of connection to the need for diversion practices in Atlanta because of the homeless populations that we all serve in some capacity. Our conversations with Redeemer had a sense of connection to the political mission of the church by holding up an image of what the kingdom of God in the world might look like through the work of PAD, calling for direct action in our congregations to address the problem of recidivism by collaborating with PAD, and cultivating strategic relationships with PAD and local leaders to make it happen. Consistently showing up to meetings and being fully present in the discussion process demonstrated trust, respect, commitment, and dependability in our shared goals. This accomplished the relationship dimension of success.

Next Steps

Considerations for the long term will include whether other congregations can be easily added into the support network based on the template established by the collaboration between Saint Mark UMC, Lutheran Church of the Redeemer, and PAD. Initial impressions based on conversations with other clergy and lay leaders at other churches located in the pilot district indicate an eagerness to join if there is a specific ask made.

The early church in the Acts of the Apostles describes exciting things happening among the people that was inspiring and encouraging.

“43 Awe came upon everyone, because many wonders and signs were being done by the apostles. 44 All who believed were together and had all things in common; 45 they would sell their possessions and goods and distribute the proceeds to all, as any had need. 46 Day by day, as they spent much time together in the temple, they broke bread at home and ate their food with glad and generous hearts, 47 praising God and having the goodwill of all the people. And day by day the Lord added to their number those who were being saved.”[9]

My hope and prayer throughout this project and the fruit that is borne from it is that the Atlanta Pre-Arrest Diversion Initiative will see many signs and wonders happen in the lives of the people diverted into services or treatment, and that all of the stakeholders will spend much time together in creative problem solving and in celebration of lives transformed. And day by day, may the Lord add to our numbers.

[1] Maria Saporta, “Settlement reached to close Peachtree-Pine homeless shelter – ending more than a decade of discord,” June 22, 2017, accessed Feb 1, 2018, https://www.bizjournals.com/atlanta/news/2017/06/22/settlement-reached-to-close-peachtree-pine.html.

[2] Gage, R. et al. 2014 “The Impact of Demographics and Sentencing on Recidivism: Non-Complex Division,” Summer 2011. Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, quoted in Office of the Fulton County District Attorney, Justice Reinvestment in Fulton County, January 7, 2016.

[3] Gage, R. et al.

[4] Office of the Fulton County District Attorney, Justice Reinvestment in Fulton County, January 7, 2016.

[5] Atlanta/Fulton County Pre-Arrest Diversion Initiative, Diversion Eligibility Data Walk.

[6] Diversion Eligibility Data Walk

[7] Tavianna Rouse (Resource Coordinator, PAD), in discussion with the author, February 2018.

[8] David Straus, How to Make Collaboration Work: Powerful Ways to Build Consensus, Solve Problems, and Make Decisions. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers Inc., 2002, p. 116-117.

[9] Acts 2:43-47.