Introduction

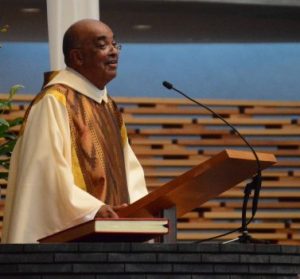

On Saturday, March 30, 2019, the San Francisco Bay Area faith community and the community-at-large suffered a tremendous loss. At 7 pm that evening, the Very Reverend James V. Matthews, II, affectionately known as Fr. Jay, died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of 70 years young. News of his death Saturday evening spread quickly and many throughout the Bay Area and beyond began to respond in shock and sadness through Facebook posts, tweets, and tributes. Several local churches, Catholic and Protestant alike posted messages on their websites in memoriam of Fr. Jay.

The Oakland Diocese shared this image Sunday, March 31, 2019 of Father Jay Matthews, rector of Oakland’s Cathedral of Christ the Light. (Courtesy Oakland Diocese)

Father Jay’s life and ministry impacted thousands of people throughout the Bay Area and around the country and even the world. Irrespective of race, religion, denominational affiliation, educational and socioeconomic status or sexual orientation, Fr. Jay was a man of the people.

He was more than a priest. He was a prophet, a teacher, a trailblazer, a change agent, a leader, a scholar, a pillar of the community, an esteemed colleague, brother, friend, mentor, advocate, and so much more.

As a change agent, Fr. Jay was the “first African American to be ordained in Northern California in 1974. He pastored St. Benedict’s Church in Oakland from 1984 to 2015 and at the time of his passing, he was the rector of the Cathedral of Christ the Light, the central cathedral of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Oakland.”[1] As an advocate and a pillar in the community, Fr. Jay “served as vicar and spiritual director of Black Catholics as a member of the Diocesan Pastoral Council during his pastorate at St. Benedict’s and served as a chaplain for the Oakland Police and Fire Department.”[2]

Most importantly, Fr. Jay was a man of God who loved God and who loved God’s people in every sense of the word. He willingly and graciously reached out to the “least of these”, those whom society has casts aside and he loved them as the children of God they are. He embodied the essence of the Gospel message of Jesus Christ with passion, compassion, and a sense of humor. Father Jayson Landeza, the current pastor of St. Benedict’s Church and Fr. Jay’s successor shared, “Father Jay responded to so many people in so many ways. That’s why he was so endearing and so much a part of this community. Matthews was known to hop on planes to help the sick or the grieving. He described one instance when Matthews opened St. Benedict Church to a Protestant couple whose church was too small for their wedding.”[3]

Dearly loved and highly respected by many, his passing is and will forever be a great loss to all of us whose lives he touched in one form or another. On Sunday, March 31st, Rep. Barbara Lee, D-Oakland, issued a statement saying, “Fr. Jay and I were “personal friends—and like many, he was there for me in good times and bad times. Father Jay lived a life of both faith and works—a life of love in service to others. We will miss his great wisdom. His passing is a loss for our entire community.”[4] So many of us echo Congresswoman Barbara Lee’s sentiment.

Image and Role of the Black Pastor

You see, Fr. Jay is the quintessential picture of what the Black pastor looks like in the African American context. Whether Catholic or Protestant, the Black pastor is called to be a voice for the voiceless, hope for the hopeless, and a guiding light not only in the church but also in the surrounding community. They are called upon to be a voice for God as well as a voice for the people. They are looked upon to speak out against systems of oppression, dehumanization, and violence and to lead the fight for social justice and equality. They are described by some as seekers of justice and lovers of peace. Undoubtedly, they are seen and upheld as the representation of God for and to the people. Edward P. Wimberly writes, “For many black people, however, the minister is a representative of God and therefore should be accorded respect.”[5]

https://www.christianitytoday.com/history/2018/february/why-enslaved-african-americans-stayed-christian.html

Dating back to slavery, the slave preacher served as a conduit between the slaves and the slave master. H. Beecher Hicks, Jr. writes, “While the master used him as a tool, he took and used it to plow up fertile spiritual ground. What seemed to the master an amusing but inept homily was laced with lessons only the oppressed could comprehend. That opium the slave master would have used as a drug, the slave preacher converted to the sweet balm that made life bearable.”[6] The slave preacher was not only focused on their own survival but they had to also be concerned for the survival of the people as a whole. Beecher goes on to state, “The slave preacher found it his function and made it his priority to aid in the psychological survival of a people. In him was discovered the unifying source, the mobilizing agent, the planner of protest, the harbinger of hope.”[7] In essence, the slave preacher’s role was one in which they were symbols of hope in the midst of hopelessness and a beacon of light in the midst of darkness.

For generations, the role and significance of the pastor in the Black church context has been unchanged although it has had to evolve as church and society has evolved over the course of time. Yet the fact remains that the Black pastor has not only been called to the pulpit but also to the public square in a similar fashion as the prophets of old in the Old Testament.

http://https://youtu.be/qKJk1rsd2lo

Edward P. Wimberly speaks to this when he states, “The black pastor reminds the people of who they are—children of God living in a hostile environment. More than this, he or she symbolizes for some people God’s engagement in the life of humankind, while for others he or she symbolizes God’s absence or hiddenness from humankind.”[8] Throughout history, the black pastor has been viewed as the central figure in the Black church.

The Black Church

Since the day our ancestors stepped foot on American soil, America has been the incubator for a hostile environment for enslaved Africans and African Americans. For this reason and many others, the Black church has always played a pivotal role in the life and well-being of African Americans individually as well as collectively. For one to understand what is meant by the term “Black Church” it is important to note that the Black church is as diverse and complex as the people who comprise it. As such, there is no ‘one’ definition of the Black church. Mary Hinton writes, “Though the black church may vary in doctrine and mission, substance and style, nearly every African-American, and most other Americans, will certainly conjure up an image of what “black church” means. Whether interpreted as a social movement, religious center, community pillar, or moral authority, the black church has, at times, meant each—and all—of these things to its members and onlookers.”[9]

At its conception, the Black church was and continues to be considered a sanctuary, a haven, a place of refuge for us from the social ills which plague us such as racism, violence, dehumanization, marginalization, poverty, discrimination, hatred, bigotry, etc. C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence H. Mamiya writes, “The Black Church has always been a spiritual refuge with a social consciousness which has at sometimes and places been more pronounced than at others.”[10] The Black church is the life line of the people she serves. Lincoln and Mamiya add, “The Black Church…recognizes human beings as both spirit and body with a duality of needs which must be addressed, because both are constantly at risk in American society.”[11]

Within the Black church, African Americans have been able to find solace, comfort, and healing for our weary souls. The church has provided us with care and compassion, instruction and affirmation of our personhood and our blackness, community, and the freedom to worship God and our risen Savior through the power of the Holy Spirit in the form of prayer, praise, and the preached Word. This atmosphere of the Black church is created by the people and led by the guidance and leadership of the Black pastor.

Personal Self-Care Journey

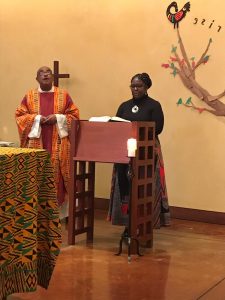

As a black pastor, Father Jay leaves a great legacy of love, faith, and service not only to and for the Catholic church to cherish but for all to cherish and to model including me. I remember where I was, what I was doing, and how I felt that Saturday evening when I received the telephone call informing me of his passing. When I hung up the telephone, I was numb. How could this be? Fr. Jay and I were just together in February. We celebrated Mass together for Black History Month at the Jesuit School of Theology. I was the preacher for the chapel service that evening, and he was the celebrant. I remember that moment as if it was yesterday. The power of God moved mightily that night. After Mass, Fr. Jay and I had dinner together and we spoke about my research on African American Clergy Self-Care. I invited him to be apart of a retreat I have plans to spearhead for African American clergy in the fall of 2019. As a member of the Board of Trustees of the Jesuit School of Theology, we had plans to see each other in May during our spring board meeting.

As a black pastor, Father Jay leaves a great legacy of love, faith, and service not only to and for the Catholic church to cherish but for all to cherish and to model including me. I remember where I was, what I was doing, and how I felt that Saturday evening when I received the telephone call informing me of his passing. When I hung up the telephone, I was numb. How could this be? Fr. Jay and I were just together in February. We celebrated Mass together for Black History Month at the Jesuit School of Theology. I was the preacher for the chapel service that evening, and he was the celebrant. I remember that moment as if it was yesterday. The power of God moved mightily that night. After Mass, Fr. Jay and I had dinner together and we spoke about my research on African American Clergy Self-Care. I invited him to be apart of a retreat I have plans to spearhead for African American clergy in the fall of 2019. As a member of the Board of Trustees of the Jesuit School of Theology, we had plans to see each other in May during our spring board meeting.

The sudden death of Fr. James ‘Jay’ Matthews has caused me to pause and to reflect upon the importance of Black ministers, particularly pastors to the Black church and the community-at-large. His death also causes me to pause and to reflect upon my own importance to the Black church and community-at-large as a minister.

At the end of August 2017, I fell ill. What seems to be overnight and out of nowhere, ¾ of my body became numb. I could barely walk. Before long I found myself having to take a Medical Leave of Absence from work, I had to cancel preaching engagements I had scheduled which is something I had never experienced in 15 years of ministry, and I was faced with the possibility of having to take a Leave of Absence from my doctoral program. It appeared as if my world was crashing down. I couldn’t understand what was happening. I wasn’t sick. I didn’t have an accident. I wasn’t bitten by an insect. In fact, two weeks before my body began to experience the numbness, I had undergone a complete physical exam which I was told came back completely normal. Except for needing to shed a few pounds per my doctor, I was completely healthy, yet my body was telling me something different.

After some convincing, I was granted permission to remain in school while I underwent a multitude of medical tests and treatments from the various doctors and specialists whose care I was under. During this time of fear, confusion, and uncertainty, I began to cry out to God in prayer. In my time before the Lord, He revealed to me the health crisis among African American clergy including myself. As a result, I sought to change the focus of my doctoral research from social justice to African American Clergy Self-Care.

Two and a half months after my body became numb, I recall sitting in the examination room of my neurologist waiting for her to share with me my tests results. When she entered the room, I was nervous to hear what the test results revealed. Undoubtedly, I was not expecting to hear what she told me. As she walked into the room, I braced myself. After greeting each other, she looked at me and said, “Your test results are normal!” I exclaimed, “How could that be possible? I know what I’m feeling in my body.” She said, “I have no doubt you’re feeling what you’re feeling.” Then she proceeded to ask me, “Are you stressed?” I laughed and responded, “Aren’t we all stressed?” She responded, “Sure but…you do know stress kills?” I froze. This was no longer a laughing matter or sarcastic moment. Admittedly, I was stressed out when I originally fell ill, and I was carrying a lot of stress.

Like many, I have a busy schedule. I work a demanding full-time job which requires me to be on-call 24/7, I am an ordained minister and at the time of my illness, my preaching schedule was intense, and I was and am still pursuing my doctoral studies. Needless to say, my plate was running over. All I had going on was enough to make anyone stressed out and sick. When I walked out of my neurologists’ office, I was not only numb physically, but I was also numb emotionally. I couldn’t help but think, “What had I done to myself?” The answer wasn’t hard to find. It wasn’t rocket science. I had gotten to a point where I simply pushed myself beyond the limit. I pushed myself so hard and so much that I wound up burned out and my body shutdown as a result.

Burnout

Through my experience I learned that burnout is real and should not be taken lightly. According to the Psychology Dictionary, burnout is “a state of extreme physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion. It is characterized by a decrease in motivation and performance. On the psychological and nervous aspect, it results from performing at such a high level of stress and tension. With prolonged exertion, it eventually takes its toll on both the body and the mind.”[12] By definition, many of us are in a state of burnout and may not even realize it. How can we not be with all that is going on in our lives as well as in the world? Every day we hear of, see, or experience a new traumatic event. When compounded with the daily stress and strain of our personal lives, it can cause life to appear overwhelming and push us to the point where we feel we just can’t add one more thing to our load. This is especially true for African American clergy who must care not only for themselves and their families but also for their congregations and the community-at-large. Undeniably, this fact could lead them to feel and believe they have the whole world on their shoulders. Wimberly writes, “Many in the black community have assigned to the black pastor wisdom and competence in all matters of living. He or she is expected to provide a worldview so that the parishioner can integrate his or her own experience.”[13] The Black pastor is looked upon to be a reservoir of knowledge, wisdom, and understanding. The pastor is expected to have all the answers to life’s questions and challenges. Wimberly adds, “Because of this assignment, many of the laity have expected the minister to be omniscient, omnipotent, and omnipresent, and to provide solutions to many earthly problems as well as to be a custodian of the values connecting them to God. Although no human could live up to these expectations, they have been operative among the laity, and the pastor has tried to live up to them as much as possible.”[14] By trying to live up to the pressures, demands, and expectations of ones’ congregation and surrounding community, many pastors have found themselves running on empty which can cause a hosts of problems, particularly, the adoption of an unhealthy lifestyle that can impact their physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being. As such, the importance of self-care in this regard cannot be understated.

Self-Care

The English Oxford Living Dictionaries defines self-care as, “The practice of taking action to preserve or improve one’s own health.”[15] Living in the fast paced, stressed out, road rage, microwave society we do, one would think it is impossible to even consider the idea of self-care. From experience, I write to inform you that self-care is not an option, it is possible, and it is mandatory for the purposes of one’s overall health and well-being. Because we may feel we don’t have the time or space to add one more thing to our calendar, we negate self-care or even the thought of it. We minimize its importance and may even go to the extreme of thinking it is selfish. Self-care is not selfish. I believe not practicing self-care is selfish. Self-care does not only impact us as individuals, but it also impacts those we are in relationship with. It also impacts how we respond within the community and society we live in. When we are healthy and whole, our state of health and well-being overflows onto those we are connected to and meet, and it allows us to be present with them in whatever space we find ourselves in. The lack of self-care has the opposite effect. When we don’t take the time to stop and rest, it can have negative consequences not only on our health (mentally, physically, spiritually, emotionally, etc.) but also on our relationships, our careers, our ministries, and even on our communities. Undoubtedly, we are busy people. We are and live in a busy society therefore we must be intentional about practicing self-care.

Self-care does not just happen. We must schedule it on our calendars and plan it out. We also must model it. This is especially true for African American clergy. As pastor, leader, and mentor, the pastor is looked to as a model even of self-care. Yet many African American clergy wear many hats. In addition to pastoring and preaching, some serve as worship planners and leaders, teachers, administrators, counselors, fundraisers, mentors, community activists, and sometimes even janitors. Without question, their plates are full. In fact, in most cases they are overflowing. As a result, it becomes even more critical for African American clergy to practice self-care. Joe E. Trull and James E. Carter writes, “A loss of health means a loss of ministry. If dedicated ministers’ pace themselves, care for their bodies, and guard their health, they can expand their ministries rather than cut them short by an early death or failing health.”[16] Because the role of the Black pastor is of great significance to the church and the community, when they are lost, not only do their loved ones suffer their loss but the church and the community suffers as well. As a result, practicing self-care is not only a gift we can give to ourselves, but it also becomes a gift we can give to those we love and to those we lead.

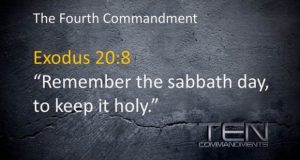

Sabbath: A Gift from God

In the Book of Exodus, we read, “Remember the sabbath day, and keep it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work. But the seventh day is a sabbath to the LORD your God; you shall not do any work—you, your son or your daughter, your male or female slave, your livestock, or the alien resident in your towns. For in six days the LORD made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but rested the seventh day; therefore the LORD blessed the sabbath day and consecrated it.”[17] This fourth commandment as given to Moses is designed for the health and well-being of all of God’s creation. During the creation account, we see God creating, modeling, blessing, and consecrating the sabbath day. God could have created and completed the work of creation in six days. Instead, God created a seventh day, a special day reserved specifically for rest, rest from our labors, rest from our worries and our anxieties, and rest from the demands and pressures of life. After creating the seventh day, God modeled it for us. The Scripture is clear when it informs us that God rested on the seventh day. The idea of God resting can appear unimaginable for some including me. My original thought was, “Why did God need to rest? Is not God all powerful?” As mighty and powerful as God is, God is also a loving Parent and knows the needs of creation, particularly the needs of humankind. God knows our need for rest therefore God made provision for us to rest during the creation of the world. The New Interpreter’s Bible states, “The affirmation about God’s rest leads to a command about human rest. In this latter accent, sabbath serves to acknowledge and enact the peculiar worth and dignity of all creatures, and especially human creatures. Consequently, there are limits to the use of human persons, and of all creatures, as instrumental means to other ends.”[18] We are God’s beloved and valuable creation. As such, during God’s creative process, God also blessed and consecrated this special day for us therefore the seventh day, the Sabbath day is sacred. The New Interpreter’s Bible adds, “Sabbath is a day of special dignity, when God’s creatures can luxuriate in being honored ends and not mobilized means to anything beyond themselves.”[19]

For as long as I can remember, the commandment to ‘honor the Sabbath and keep it holy’ has been associated for Protestants with going to church on Sunday mornings for worship. As a result of this research, I’ve discovered that that is not a correct interpretation of the Sabbath especially when we consider that Sunday morning is a workday for clergy especially African American pastors and clergy. In proposing the adoption and implementation of Sabbath into ones’ self-care practices, there is also a need to propose that African American clergy find a day other than Sunday for sacred rest. This is possible with the understanding that honoring the Sabbath is not about a certain day of the week, it is about the practice itself. Abraham Joshua Heschel writes, “Observance of the seventh day is more than a technique of fulfilling a commandment. The Sabbath is the presence of God in the world, open to the soul of man. It is possible for the soul to respond in affection, to enter into fellowship with the consecrated day.”[20] Sabbath is our opportunity to be one with ourselves, one with God, and one with creation in a way that the other six days do not allow us to be. As such, may we honor this gift given to us by being present to receive the blessings of rest and renewal that God has in store for us.

Conclusion

I believe African American pastors and clergy are precious gifts to the Body of Christ and to the community-at-large. In fact, I believe we are all precious gifts. We not only possess gifts within us but we, ourselves are a gift. We are a gift from God to humanity, particularly, to our loved ones and to our community. Although we may not always feel or even perceive ourselves as a gift, the fact remains that we are indeed a gift. And as the precious gifts that we are, it is imperative that we become intentional about practicing self-care. God uniquely and purposefully created only one of us. We are an original, we are one of a kind. If we are lost, the loss of our presence will be felt by those whose lives we’ve impacted knowingly as well as unknowingly.

Not taking for granted the fact that life is stressful and at times overwhelming and that many of us are doing all we can to make ends meet is understandable, yet we must take time to consider the costs. Through my illness two years ago, I realized I could have money in my bank account and obtain all the success I could imagine yet not have my health, I have nothing. The importance of our health and well-being goes without saying. Implementing Sabbath rest into our self-care routine is one way we can cherish the gift of life God has entrusted to us.

The practice of Sabbath is about us being and not doing. It is an act of cessation from our labors not forever but indeed for a moment in time. The gift of Sabbath given to us by God is a gift of time. May we unwrap it and utilize it in the manner God intended at the creation of the world.

SHABBAT SHALOM (SABBATH PEACE)

http://https://youtu.be/sNQZf3avz84

[1] Dominic Fracassa, “Father Jay Matthews, trailblazing Oakland priest, dies at 70”, San Francisco Chronicle, last modified March 31, 2019, accessed Thursday, April 4, 2019, https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Father-Jay-Matthews-trailblazing-Oakland-13730718.php.

[2] Ibid, 2.

[3] Ibid, 3.

[4] Ibid, 3-4.

[5] Edward P. Wimberly, Pastoral Care in the Black Church (Nashville: Abingdon, 1979), 36.

[6] H. Beecher Hicks, Jr. Images of the Black Preacher: The Man Nobody Knows (Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 1977), 39.

[7] Ibid, 39.

[8] Edward P. Wimberly, Pastoral Care in the Black Church (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1979), 36.

[9] Mary Hinton, The Commercial Church: Black Church and the New Religious Marketplace in America (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2011), 11.

[10] C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence H. Mamiya The Black Church in the African American Experience (Durham: Duke University, 1990), 397.

[11] Ibid, 397.

[12] Pam N., M.S. Psychology Dictionary, April 7, 2013, https://pscyhologydictionary.org/burnout/(accessed March 29, 2019).

[13] Edward P. Wimberly, Pastoral Care in the Black Church (Nashville: Abingdon, 1979), 36.

[14] Ibid, 36.

[15] www.en.oxforddictionaries.com (accessed March 29, 2019).

[16] Joe E. Trull and James E. Carter Ministerial Ethics: Moral Formation for Church Leaders (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2004), 67.

[17] Exodus 20:8-11, New Revised Standard Version.

[18]Walter Bruegmann, “The Book of Exodus: Introduction, Commentary, and Reflections,” in The New Interpreter’s Bible (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1995), 846.

[19] Ibid, 846.

[20] Abraham Joshua Heschel The Sabbath (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1951), 60.