By Willie Dwayne Francois III

The Problem

More than individual acts of discrimination, White racism persists as a form of power that works beneath the consciousness of human subjects[1], regardless of their racial identity, and animates U.S. institutions and systems. Whiteness lives within and around all of us. The overwhelming White Christian support of and complicity with slavery, lynch culture, Jim Crow Segregation, and now the normalization of Black hyper-incarceration drafts U.S. Christians into the fight for dismantling the Prison Industrial Complex. In each epoch of strategic disinheritance of Black people in America, White Christians sacralized Black oppression, perpetuated injustices, or hid under heavy silence.

Nevertheless, the predominance of American Christians, explicitly White Christians, reject complicity with racism and further claim to be non-racists. However, non-racist is not a real ethical orientation or identity. Non-racist is a pseudo-neutral position that allows racism to persist and ravage human lives and society. The world needs more Christian antiracists—people committed to the way of Jesus of Palestine in a way that combats racist policies, practices, and perspectives, namely related to the U.S. criminal justice system.

Mass incarceration lives at the intersection of racial terror, class stratification, and the myth of public safety. Though the U.S. is only five percent of the world’s population, it houses 25% of the world’s incarcerated people. From 1865 to 1968, a total of 184,901 Americans entered state and federal prisons. From 1968 to the early 1980s, America housed 251,107 in its prisons. Today, incarceration sits at 2.2 million, half of which is nonwhite. Startlingly, incarceration has increased by 943% in the last 50 years. By the end of 2016, more than 6.5 million Americans were behind bars, on probation, or parole—some form of detainment and surveillance.[2]

The white imaginary criminalizes Black bodies out of inherited fear and a need to maintain white power.

In 2017, according to Pew Research Center, black people represented 12% of the U.S. adult population and 33% of the prison population, while Latinx persons comprised 23% of the prison community despite representing only 16% of the national adult population. Demonstrating the racial inequity of incarceration, White Americans account for 30% of U.S. incarcerations, although they make up 64% of the U.S.[3] Mass Incarceration functions as public policy like Jim Crow and Chattel Slavery without the guilt.

The limited Christian solidarity concerning anti-incarceration advocacy symptomizes a collective failure to address the histories of Whiteness, the structural realities produced by those histories, and the longevity of structural racism in the U.S. My project explored the linkages between racial identity and Christian identity and how they shape our assumptions and perceptions of the criminal justice system in the U.S. and worked toward a model of Christian antiracism pedagogy as a resource for spiritual formation and anti-incarceration public policy advocacy.

Given the context of the hyper-politicization of White Evangelicalism and the struggles of antiracism to upend structural white supremacy, Christians must nurture the capacity of antiracist critiques of and advocacy for public policy.

I established a pedagogical practice that mobilizes Christians—across racial identities—into networks of self-reflective, structurally focused, and theologically rooted post-white advocacy. This project conjoined Christian antiracism pedagogy with anti-incarceration work, contending that the effective education and mobilization of Christians—in multiracial, resistive networks—to combat Mass Incarceration from a structural approach requires centering the problem of white power, unmasking the complicity of U.S. Christianities in said system, tracing the history of Black criminalization, and attending to our collective and personal inner wisdoms in self-confronting small-groups of learning.

The Project

As one of its strategic projects, the Black Church Center for Justice and Equality (BCC)—a D.C.-based national policy advocacy organization and theological think tank—equips congregations interested in undertaking anti-incarceration advocacy and forming multiracial networks of grassroots advocacy. As President of the BCC, I initia ted interracial clergy roundtable project—racial equity training—to help pastors transcend racial distance and address White Christian apathy, at best, and white Christian antagonism, at worst, toward nonwhite structural suffering. However, the racial equity training lacked an explicitly theological framework and issue-specific advocacy agenda. The pedagogical innovation born out of the Doctor of Ministry program solved for both limitations by foregrounding liberation theology, layperson engagement, and advocacy to end mass incarceration.

ted interracial clergy roundtable project—racial equity training—to help pastors transcend racial distance and address White Christian apathy, at best, and white Christian antagonism, at worst, toward nonwhite structural suffering. However, the racial equity training lacked an explicitly theological framework and issue-specific advocacy agenda. The pedagogical innovation born out of the Doctor of Ministry program solved for both limitations by foregrounding liberation theology, layperson engagement, and advocacy to end mass incarceration.

By the Numbers

To quantify public perceptions of the U.S. criminal justice system, I designed a survey aimed to gather a sample of Christians in the BCC network 1) to learn the average level of literacy of Mass Incarceration, 2) discover any existing theological/ecclesiological themes related to mass incarceration and race, and 3) gather a sense of existing assumptions about race and U.S. legal system for Black and center-left white Christians. The survey anonymously captured the sentiments of 881 Christians, largely Black and center-left White. In this sample, 78% of respondents self-identified as Black, 18% white, and slightly less than 1% as Latinx, which established a national context for developing the pedagogical practice.

The Art of Christian Antiracism

The “core essences” of Christian antiracism education include: 1) embracing the divinity of difference and equality in c reation, 2) operationalizing definitions of race/racism and centering Whiteness, and 3) understanding the centrality of relationality—the interpersonal and inter-structural respectively. This pedagogy leans into the idea that better relationships and clear structuralist awareness deepen a sense of duty for activism and advocacy. The theory of change influencing the life of the project pivots on a small-group pedagogy anchored in radical mutuality, self-narrativity, and liberationist praxis. This pedagogical endeavor invites people beyond their enclaves of racial isolation through role-play, artistic reflections, introspective narration, and theological criticism. The hope is for everyday Christians to develop the necessary skills to formulate local political strategies, cultivate networks of power accountability, practice interracial risk-taking, and facilitate community education and mobilization.

reation, 2) operationalizing definitions of race/racism and centering Whiteness, and 3) understanding the centrality of relationality—the interpersonal and inter-structural respectively. This pedagogy leans into the idea that better relationships and clear structuralist awareness deepen a sense of duty for activism and advocacy. The theory of change influencing the life of the project pivots on a small-group pedagogy anchored in radical mutuality, self-narrativity, and liberationist praxis. This pedagogical endeavor invites people beyond their enclaves of racial isolation through role-play, artistic reflections, introspective narration, and theological criticism. The hope is for everyday Christians to develop the necessary skills to formulate local political strategies, cultivate networks of power accountability, practice interracial risk-taking, and facilitate community education and mobilization.

The Practice

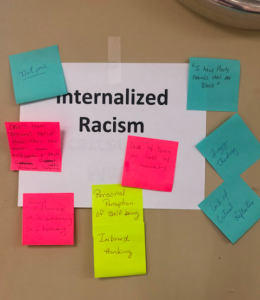

Exploring the intersectionality of race, religion, and criminal justice, the 15-hour pedagogical practice—spiritual formation praxis—articulates 1) racism as a form of structural power that advantages some and oppresses others along the lines of skin color and racial identity and 2) race as a social construct with grave implications on religious, political-economic and social lives, 3) mass incarceration as a form of social control in the lineage of chattel slavery and Jim Crow segregation, and 4) how U.S. Christianities are complicit in maintaining mass incarceration as a racialized form of social control.

Session One—Freedom Works: Foundations of Antiracism and Self-location

Session Two—Branded from Birth: Mass Criminalization and Anti-blackness around us, in us

Session Three—Forward Disruptions: Antiracism, Renewing our Theology, and De-carceration

Over eight weeks in the fall of 2019, two separate groups participated in the designed Christian antiracism training. The Atlantic County cohorts developed from invitations extended to a white Universalist Unitarian congregation, a white Presbyterian church, one Black congregation, and one Latinx church. The training convened at Mount Zion Baptist Church in Pleasantville, New Jersey, where I have served as Senior Pastor since December 2015. Each group engaged in 15 hours of instruction, reflective practices, and small-group exercises for three consecutive Saturdays (two three-session Christian Antiracism trainings). The first cohort consisted of 13 learners, while 18 participants composed the second cohort—88% female, 11% male, 95% black, 5% white.

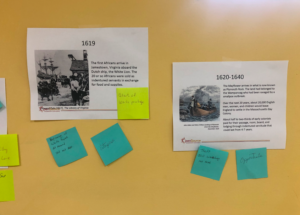

One of three equally timed sessions, the first session—through a lecture and four small-group reflective exercises—worked to establish a community of trust, operationalize key terms, explicate assumptions concerning the function of race and racism in the U.S., and resource to learners to locate themselves in this unfolding history.  The aim pivoted around exploring one’s racial biography alongside the story of race in the U.S. The second session, also designed with the same schedule, delved into Mass Incarceration as a form of social control, exposing learners to thick excerpts from Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.

The aim pivoted around exploring one’s racial biography alongside the story of race in the U.S. The second session, also designed with the same schedule, delved into Mass Incarceration as a form of social control, exposing learners to thick excerpts from Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.  This practice offered a history of Black criminalization and its antecedents, and data associated with the economics of incarceration. Participants undertook exercises meant to explore implicit bias and assumptions about the criminal justice system. This session sought to educate about racism and incarceration, while preparing people for protest, public policy advocacy, and protecting people from the ravishes of the Criminal Injustice System.

This practice offered a history of Black criminalization and its antecedents, and data associated with the economics of incarceration. Participants undertook exercises meant to explore implicit bias and assumptions about the criminal justice system. This session sought to educate about racism and incarceration, while preparing people for protest, public policy advocacy, and protecting people from the ravishes of the Criminal Injustice System.

In the final session, the participants explored questions of privilege—white, male, heterosexual, citizenship, upper-middle-class, education—and the curious role of theologies in the U.S. and the extent to which privilege and theologies can be used to disrupt Mass Incarceration. Moreover, this session dedicated significant time to group strategies and individual behavior modifications aligned with antiracism and anti-incarceration advocacy. The design intended to prepare people to undertake advocacy on personal, communal, and structural levels. Consistently, the training demonstrated a belabored emphasis on race as systemic and structural and Mass incarceration as one of its many manifestations.

Unexpected Findings

From the Survey

Two-thirds of White respondents revealed they discriminated against a person because of race. At the same time, 30% asserted they had no personal experience with racial discrimination. A fifth of these White Christians even indicated they had been discriminated against for their white identity, which paled in comparison to the 95% of Blacks who lived on the underside of racial discrimination.  Curiously, 21% of Black Christians owned discriminating against persons of other races. When asked if they believed some negative racial stereotypes were true, 51% of Black respondents answered affirmatively over against the 33% of white Christians giving the same answer. This underscored how Whiteness lives in nonwhite bodies.

Curiously, 21% of Black Christians owned discriminating against persons of other races. When asked if they believed some negative racial stereotypes were true, 51% of Black respondents answered affirmatively over against the 33% of white Christians giving the same answer. This underscored how Whiteness lives in nonwhite bodies.

The overwhelming majority of survey respondents endorsed an ecclesiological framework for social justice engagement. They saw local churches as potential incubators for social change related to disrupting the Prison Industrial Complex. Therefore, the lack of “church work” dedicated to ending mass incarceration, in light of the beliefs that churches should work toward criminal justice reform, highlighted a need for a pedagogical practice that creates opportunities for advocacy and engagement.

The national survey also exposed some of the gaps in knowledge related to the U.S. criminal justice system and its impact on hegemonic Whiteness and the racial hierarchy. While most participants of the workshops and survey named racism as a constitutive feature of the Prison Industrial Complex, the overwhelming majority lacked awareness of the data on policing, post-incarceration discrimination, and the complicit role of religion.

The Practice

To measure the effectiveness of the training, I probed with questions about their feelings, learnings, and intention-setting through a post-training survey. At the close of the third session, more than 90% of workshop participants indicated new intentions to incorporate antiracism into their daily experiences. Per the exit assessments,[4] A group of 13—the first cohort—committed to sharing their new learnings about Christian antiracism and anti-incarceration with a range of 35-150 persons, pushing the reach of a single training to two to eleven times the rate of attendance. Roughly a quarter of the aspiring antiracist Christians estimated disseminating their learnings, facilitating conscientizing practices, or recruiting among 20 or more persons in their network. At the same time, 38% of the attendees believed they could influence six to ten persons toward antiracism and anti-incarceration advocacy. Another 30% of the participants registered their post-session contacts around one to five people.

The preponderance of enumerated behavioral objectives could be categorized as communal methods of local change over against structural and personal approaches. After 15-hours of focusing on racism and incarceration in the U.S., persons devoted the ensuing six months to 1) pursuing a reading program for students with low reading scores, realizing third literacy rates mirror prison expectancy, 2) researching a landscaping program operative in P.A. to help returning citizens gain employment and not return to prison, factoring in one of the leading contributors to recidivism, 3) assisting young people and young families to navigate and avoid structural traps, and 4) launching book clubs. A small group, in both trainings, committed to nonviolent direct action and meetings with state legislators and city council members. Of the 27 participants who fulfilled the entire three sessions, 89% of these Christians also committed to a 66-day Antiracist Habits Challenge—readings, recitations, videos, audios, experiences, interpersonal interactions, and social action.

After 15-hours of focusing on racism and incarceration in the U.S., persons devoted the ensuing six months to 1) pursuing a reading program for students with low reading scores, realizing third literacy rates mirror prison expectancy, 2) researching a landscaping program operative in P.A. to help returning citizens gain employment and not return to prison, factoring in one of the leading contributors to recidivism, 3) assisting young people and young families to navigate and avoid structural traps, and 4) launching book clubs. A small group, in both trainings, committed to nonviolent direct action and meetings with state legislators and city council members. Of the 27 participants who fulfilled the entire three sessions, 89% of these Christians also committed to a 66-day Antiracist Habits Challenge—readings, recitations, videos, audios, experiences, interpersonal interactions, and social action.

Future Implications

This project paved ways toward two new concepts for my theological inquiry—post-white advocacy and resurrective justice—that the constraints of the written component disallowed me to exhaust. Post-whiteness represents a decision to break from the logic of white racism, while resurrective justice offered a thoroughly theological way of understanding justice for communities disproportionately impacted by mass incarceration and mass criminalization.

Ending Mass criminalization requires changing hearts and minds, while ending mass incarceration requires changing systems. The normative gaze of the western world venerates Whiteness and devalues the other, namely Blackness, as some-thing to be managed and rejected. The exceptionalism of the U.S. centers a civic religious ethos about the sacredness of Whiteness and the guiltiness, dangerousness, and sinfulness of Blackness.[5]

Any power, to draw from Paul Tillich, that impairs human flourishing, autonomy, and creativity is demonic. The categorical demonization of a class of people is demonic. The model teaches that the criminalization of Black bodies is demonic. Whiteness is demonic.

Therefore, the project framed “the next steps” as white exorcistic practices—post-white advocacy. We can exorcise demonic Whiteness. Therefore, post-whiteness is a moral choice to radically and consistently divest politically, economically, theologically, and emotionally from white privilege, power, and mythic superiority, working towards racial repair and equity. This racial conscientization serves the ends of emptying embodied experience, ecclesiologies, and politics of the naïve and conscious violence and terrors of white structures—a type of white kenosis.

There is a need for post-whiteness Christian witness in the world.

Relatedly, Resurrective justice, at the risk of oversimplifying, centers on the reclamation of life amidst a layered, interlocking, and long-tenured culture of social death native to the era of Mass Incarceration. The symbol of the resurrection offers a theological heuristic for understanding justice in a society structured to criminalize entire classes of people, thereby creating a racial caste, through systematic racialized practices of punishment and social control.  Ecclesial participation in criminal justice reform is a form of resurrective justice—practices that humanize the formerly incarcerated, establish a livable economic floor for communicated historically impacted by Mass incarceration, and secures the rights of humanity and citizenship for impacted communities. I will continue to flesh out Post-white advocacy and resurrective justice in the context of Christian antiracism and how the concepts intersect.

Ecclesial participation in criminal justice reform is a form of resurrective justice—practices that humanize the formerly incarcerated, establish a livable economic floor for communicated historically impacted by Mass incarceration, and secures the rights of humanity and citizenship for impacted communities. I will continue to flesh out Post-white advocacy and resurrective justice in the context of Christian antiracism and how the concepts intersect.

Next Steps

Though the overall goal is to empty our Christianities of the logic of Whiteness irrespective of one’s racial identity, one of the growth opportunities for the project relates to recruiting more White Christians to the educational exp erience. The pilot practices overwhelmingly attracted Black participants, but a fundamental component for upending racism is creating more White Christian antiracists.

erience. The pilot practices overwhelmingly attracted Black participants, but a fundamental component for upending racism is creating more White Christian antiracists.

I, additionally, plan to scale the curriculum for class size and length to adapt to the needs of given settings—local churches, denominations, conferences, community organizations, and other civic groups. There exists an opportunity to adapt this curriculum for digital learning and online community-building. A highly structured digital curriculum makes antiracism and anti-incarceration advocacy accessible to more communities, which also raises ethical questions around online learning and facilitation.

Works Cited

[1] Cornel, West. Prophesy Deliverance!: An Afro-American Revolutionary Christianity. (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2002), 54.

[2] Cowhig, Mary & Danielle Kaeble, “Correctional Populations in the United States, 2016.” Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice (Washington: April 2018), 1. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus16.pdf

[3] John Gramlich, ‘The Gap Between the Number of Blacks and Whites in Prison is Shrinking.” FactTank: News in Numbers. (Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center, April 2019). https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/30/shrinking-gap-between-number-of-blacks-and-whites-in-prison/

[4] Exit surveys were distributed at the end of the third session of both trainings. Surveys were complete onsite and analyzed two weeks after the training.

[5] Kelly Brown Douglas. Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God. (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2015), 79.