ENGAGING RURAL CONGREGATIONS TO EMBRACE RACIAL DIVERSITY: THE EXPERIENCE OF A UNITED METHODIST PASTOR SERVING IN CROSS-RACIAL/CROSS-CULTURAL APPOINTMENT WITHIN THE GREAT PLAINS ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH

INTRODUCTION

The Great Plains Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church has operated out of an assumption that cross-racial/cross-cultural appointments can be best addressed through workshops and conversations. Through this project, I examined issues on the part of a first-generation West African-America pastor serving in cross-racial/cross-cultural appointments in the Great Plains Annual Conference to determine the effectiveness of the current process of preparing both pastors and congregations for cross-racial/cross-cultural ministry. Based on the responses I received from this study, I have decided to offer suggestions which, if adopted, may strengthen the process currently in place.

This project is a result of my reflection on my journey of ministry in a cross-racial/cross-cultural rural appointment. The willingness of God’s people to embrace each other can also lead the church to experience the presence of God. The ministry of the Apostle Paul is an example of the empowerment of the Holy Spirit to reach out to the people in their cultural context. Paul’s ministry reminds us that in Christ, there is no discrimination; we are all God’s children saved by God’s grace through Jesus Christ. The understanding of cross-racial/cross-cultural ministry is a step toward the building of God’s Kingdom on earth, that is open to all people- Jews and Gentiles, males and females, Black, White, Africans, Hispanic, and Asians without any discrimination. This project also examines the perceptions, feelings of inadequacy, isolation, negativity, racism, and lack of support and connectedness caused by racial and cultural differences between the writer and the congregations to which the writer was appointed to serve.

This project first started at the Saint Paul United Methodist Church in Saint Paul, Nebraska. It concluded at the Ewing United Methodist Presbyterian Church, Ewing, Nebraska, Orchard United Methodist Church, Orchard, Nebraska, and the Page United Methodist Church, Page, Nebraska. This project is a call to action in these rural churches, where God “is still searching for people to trust Him to do the impossible in places where the impossible is all that will work.” Because this project focused on these four churches, and for this project, instead of individually listing these churches, the author will use the phrase “rural churches” to represent all four congregations.

This project used qualitative methodology, which is exploratory, subjective, and describes specific groups in a particular context. The project used a participant survey, small group studies, the Great Thanksgiving for Cross-Cultural/Cross-Racial Ministry during selected Communion Sundays, and a Liberian meal, with the project goal to equip these rural churches to embrace racial diversity.

Serving God through cross-racial/cross-cultural appointments is a task that requires not only personal effort but God’s support. Cross-racial/cross-cultural ministry has many sensitive issues that some of the project participants (congregants) felt uncomfortable talking about or giving their opinions. Unlike what some people thought, I did not use questionnaires to evaluate the leaders of the Staff Parish Pastor Relation Committee (SPPRC). However, I used the surveys to help me learn from the experience of leaders and congregants. I felt honored to hear from the project participants and those that I identified at the beginning of this project. While the questionnaires had many questions, some of them were to lead me to what I needed, while others were crucial questions that helped me get enough information from all the participants. The group discussions with the leaders and communities were another opportunity to listen to the congregants and communities describing their experiences and challenges faced with cross-racial/cross-cultural clergy appointments. Through the questionnaires and group discussions, I felt satisfied with the information I received from all the participants. The congregation in my appointment felt nervous initially, but once they got to know me and I got to know them, our anxieties were reduced.

To make cross-racial/cross-cultural ministry effective, both the clergy and the congregation should become more culturally aware and sensitive. Cross-racial/cross-cultural ministry allows the Church to bring different cultures together for the same purpose. With adequate preparation, cross-racial/cross-cultural appointed clergy can provide the bridge between two cultures. They can mediate between the cultures. Moreover, the goal of cross-racial/cross-cultural ministry is not to have tolerance nor increase sensitivity toward racial and cultural differences. It is to journey beyond understanding and sensitivity.

Through this journey, we can accomplish the mission of the gospel because, through Christ, the goal of the triune God for the healing and salvation of all humankind becomes the Christian’s goal. The Church’s unifying mission and purpose, the tie binding all together as one, is expressed by Jesus Christ in John 17:21. As Jesus intercedes on behalf of all his followers, “that they may all be one; even as You, Father, are in Me, and I in You, that they also may be one in Us; that the world may believe that You sent Me.” Hence, we, as a community of believers, are intentionally seeking to understand ourselves as racial and cultural beings through cross-racial/cross-cultural education and training. Moreover, as people in the image of God, it is befitting that we have the servant’s attitude best illustrated by Jesus in John 13:1-17. I hope that with the help of God’s Spirit, these suggestions will also help the United Methodist Church overcome challenges of cross-racial/cross-cultural clergy leadership and prepare competent ecclesial leaders to lead in God’s work.

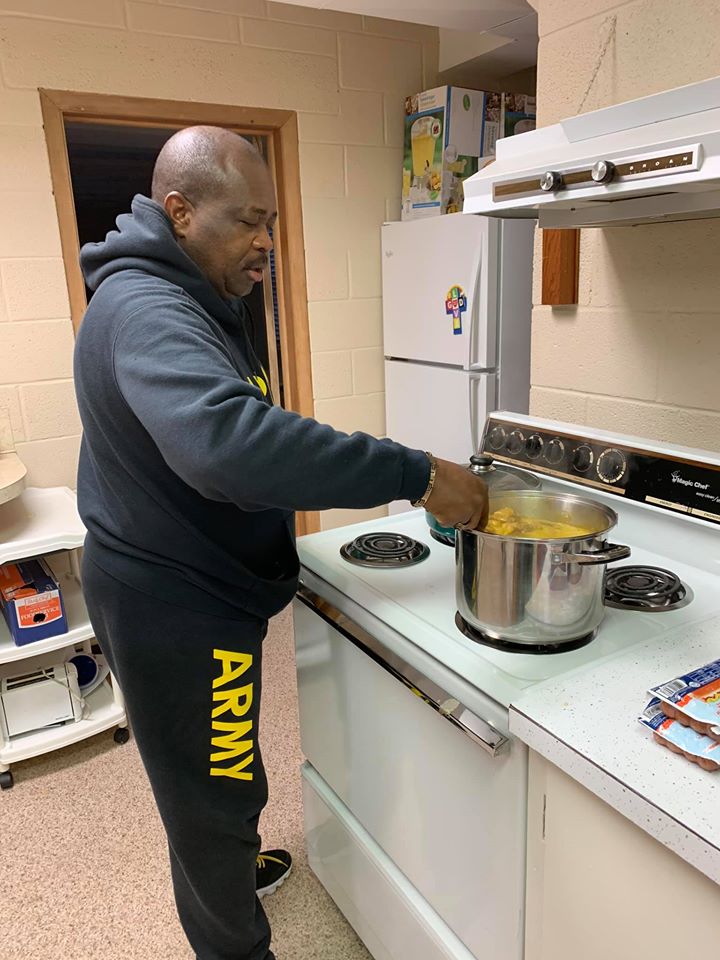

Pastor Larmena is preparing Palm Butter and Chicken Feet. Pastor Larmena is also serving in the United States Army at the Rank of Major.

Learning from the Project

The experience of crossing cultural boundaries for God’s sake found its foundation in the Scriptures of both the Old and the New Testament. Through the sending out of Abraham to live away from his nation, his family and his culture reveal God’s plan to reunite the world that was divided at Babel. Abraham’s hospitality to strangers offers a foundation for cross-racial/cross-cultural ministry; his reception to the sojourners led him to welcome God by the oaks of Mamre.[i] In his article, “Hospitality to Strangers,” Kenneth Gibbs says, “People who look different from us, who speak another language, who have a darker color of skin, who practice a different life-style, make us afraid or even hostile. But, ‘do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers,’ says the Scripture.”[ii] Sometimes the presence of strangers or people who don’t look like us or who speak different languages from us but who want to be embraced in our communities has been the subject of fear. This fear (may be caused by who we are, how we look like, where we are from, or what we heard about a particular group of people) has grown even in the Christian community where strangers feel sometimes excluded.

The attitude of Abraham to strangers was not from the feeling of fear of being away from his culture or being surrounded by strangers. Still, it was a response to God’s calling that transcends all human cultural prejudices. This attitude becomes an example of how Christians should embrace each other unconditionally. Like Abraham, by embracing strangers, we experience the presence of God through each other. The attitude of Abraham to God and strangers becomes a picture of how clergy should obey God’s calling, and also how both congregations and pastors should embrace each other. Through cross-racial/cross-cultural appointments, both clergy and congregants have the opportunity to welcome each other. These appointments offer a chance to see the invisible God through our differences. In other words, cross-racial/cross-cultural appointments challenge both clergy and congregations to go beyond their comfort zones for the sake of Christ. They provide an opportunity for Christians to value the work of God, who created us all in God’s image to become members of one body of Christ.

In my ministry setting, I have gone from a place of fear and fault to one of gifts, generosity, and abundance,[iii] which occurred through honest self-awareness and a transformative process in our community. It seems to have taken four years in pastoral ministry as a West African-American Pastor in these European-American rural churches to overcome the loss of everything that I have counted as gain, as seen in Galatians 1:15-18. Pastoring in these rural churches was also a humbling experience. With all the training and education, God made sure that I started at the bottom rung, as we all do, to give me the knowledge that we are all broken. With this experience, I can set out in the right direction with a determination to become all that God has created me to be ministering in a community of believers. The real community comes only through the work of the Cross and the resurrection power of the Holy Spirit. As this project concludes, to be an effective pastoral leader, one will go through painful (refining fires) desert experiences. Such “refining fires” shape the pastoral leader to become a Christ-centered disciple, able to be a clergy, theologian, prophet, and community witness under the Holy Spirit’s direction, prepared for the changes taking place. To access the shift, the pastoral leader can incorporate the use of community assets and spiritual mapping. Spiritual mapping will expose strongholds that need to be broken by intensive, strategic, and persistent intercessory prayer, and community asset mapping will provide the tools for rural community development.

During this pastoral journey, the congregation is now comfortable eating traditional Liberian dish -Palm Butter and Chicken Feet.

Using these tools, both the communities and clergy grew in faith, sought more of God, and released control to the Holy Spirit, a renewed journey of God evolved, trusting the unknown to the Holy Spirit. The world then is seen as a sacrament, along with the rebirth of unity and the embrace of pain. Compassion began to flow amongst the members and out to the broader community. Healing became evidenced, and a place of refuge established.

In response to what I have learned through this study, I have emerged from my temporary mono-racial familiarity. I have awakened to the unexpected opportunities for multicultural ministry that God is miraculously placing before me. With excitement, I am developing, with the aid of other pastors and leaders in the congregation, a growth plan for multi-cultural/multi-racial ministry.

[i]Genesis 18:1-21

[ii]Kenneth Gibbs, “Welcome Strangers Source: Brethren Life and Thought.” 26, no. 3 (Sum 1981) 184-188. (ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials.)

[iii] Peter Block. Community: The Structure of Belonging (Oakland: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., 2009), 73.