INTRODUCTION

What does it mean in particular to be a Christian and to be Vietnamese-American, and what makes it unique?

For many second-generation Vietnamese Americans, knowing how to express their dual identity is a daily concern. And it is a concern that each generation has to work out for itself, as respected Vietnamese-American Catholic theologian Peter C. Phan notes: “the challenges facing Vietnamese-Americans, while overlapping to a certain extent, are distinct for each generation.”[1] He explains that “for those of the second and third generations, who often speak English fluently and broken or no Vietnamese at all,” the challenges are “not so much how to fit into American culture and society but [how] to define themselves racially, ethnically, and culturally.”[2]

Religious affiliation only deepens this quandary, this living at the intersection of identities. So, what does it mean in particular to be a Christian and to be Vietnamese (-American), and what makes it unique? Daniel C. Owens, a lecturer at Hanoi Bible College in Vietnam, recognizes that many believers in any culture “must confront this kind of fundamental question, and it deserves careful theological reflection.”[3] In an especially multicultural and multi-ethnic society like the US, the question is all the more pressing. Our biblical forebears also had to address this question. Not surprisingly, the biblical record prioritizes one’s relationship to God. We see an example in 1 Peter 2:10 (NRSV), which boldly reminds believers: “Once you were not a people, but now you are God’s people; once you had not received mercy, but now you have received mercy.” Although Vietnamese Christians could rightly claim their identity as “God’s people,” it is fair and indeed life-giving for them to want to find a new way of expressing their faith and cultural heritage in their mission and community, a way that honors both.

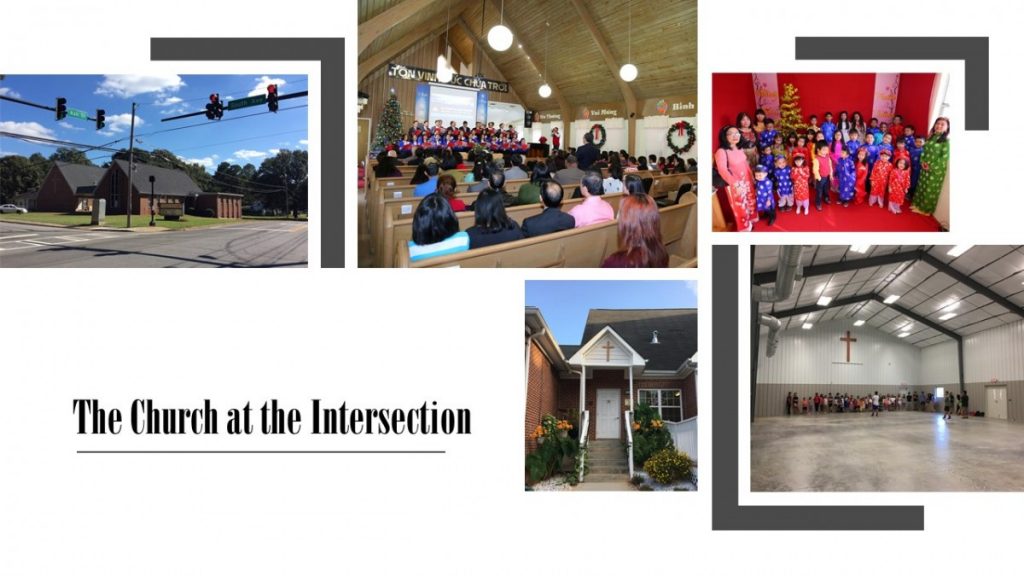

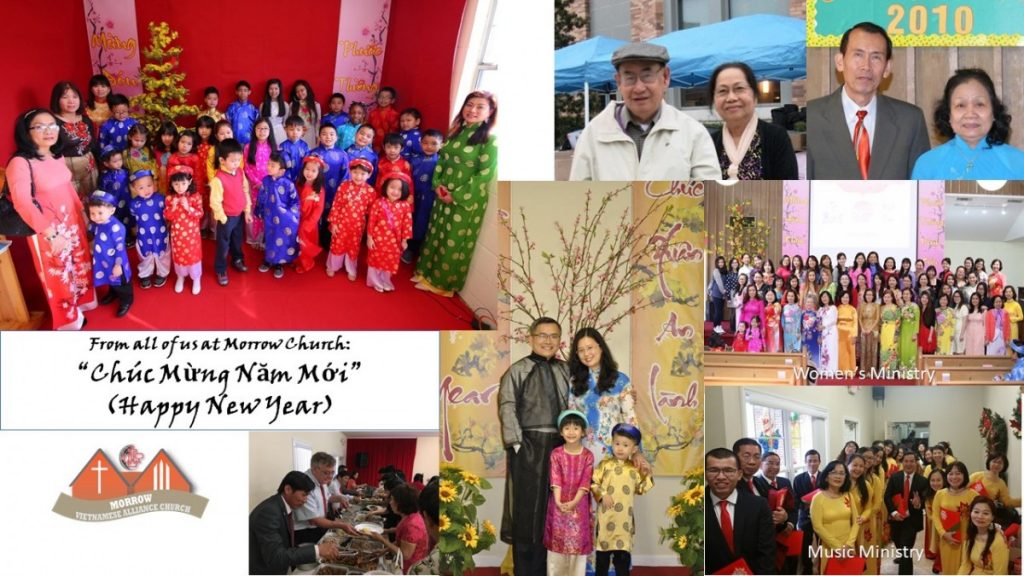

Morrow Vietnamese Alliance Church (MVAC), a member church of the Vietnamese District in the Christian and Missionary Alliance (C&MA), was officially established on July 1, 1995, with forty-five founding members. The church sits at the corner of Ash Street and South Avenue in Morrow, a town to the southeast of Atlanta, reflecting our position as a people as the intersection of both Vietnamese and American cultures and first- and second-generation Vietnamese Americans.

As a pastor at Morrow Vietnamese Alliance Church (MVAC), I am particularly interested in discovering ways in which we can hold together all the different aspects of ourselves when we worship God as Vietnamese-American Christians. How can I as a pastor together with my congregation support second-generation Vietnamese-Americans, and in so doing benefit the broader Vietnamese-American communities in the Atlanta region? How do we do this when we are rapidly forgetting or putting out of mind our rich Vietnamese cultural heritage and identity? Why not marry the two traditions and celebrate the Eucharist at Tết, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year celebration?

Tết Nguyên Đán, or Tết for short, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year (VLNY) celebration, is particularly central for those who identify themselves as Vietnamese-Americans because it is the national, most important, popular holiday and festival in Vietnam and for Vietnamese around the world. Likewise, the Eucharist is a central religious practice for those who follow the Christian faith. Rooted in “the deepest traditions of Christ’s church,” Christians have for two thousand years gathered to “do this in remembrance” of the risen Christ. The Eucharistic celebration is at the heart of our “identity as the people of God through our participation in prayer, song, proclamation, and the ritual action around the table of the Lord.”[4] Living Eucharistically has been the practice from “the earliest church in Jerusalem; it continued in the apostles’ teachings, the fellowship, the breaking of bread and ongoing prayers (Acts 2:42ff),” and is celebrated by millions of Christian churches in the United States and around the world.[5]

CONSTRUCTING A EUCHARISTIC CELEBRATION AT TẾT

In my project, I would like to construct a Eucharistic celebration during Tết and to offer my suggestions on how Vietnamese-American Christians might worship God during Tết. I do so by presenting a quick glimpse of what Tết is and its context, how Tết is celebrated in Vietnam and in the United States, some thoughts on Vietnamese culture and its religions, the fear of syncretism due to ancestor worship among Christians in the Tết celebration, and some guidelines for how to construct a Eucharistic celebration at Tết without the fear of syncretism in the community of Vietnamese Christian churches.

In the face of current challenges on worship and culture, many scholars worldwide have worked together on the biblical and historical foundations of the relationship between Christian worship and culture. The Nairobi Statement on Worship and Culture in January 1996 presents four central principles for the relationship between worship and culture that are worth considering for our Vietnamese-American context: the transcultural, contextual, counter-cultural, and cross-cultural.[6] These four principles will guide Vietnamese-American Christians in constructing their Eucharist celebration of Tết by affirming: “Worship is the heart and pulse of the Christian Church. In worship, we celebrate together God’s gracious gifts of creation and salvation and are strengthened to live in response to God’s grace. Worship always involves actions, not merely words. To consider worship is to consider music, art, and architecture, as well as liturgy and preaching.” [7]

- Worship is transcultural.

By acknowledging that “the sacrament of Christ’s death and resurrection were given by God for all the world” (2.1), the Eucharistic celebration for Tết will follow the fundamental shape of the Eucharist, which is: “the people gather, the Word of God is proclaimed, the people intercede for the needs of the Church and the world, the eucharistic meal is shared, and the people are sent out into the world for mission” (2.1).

- Worship is contextual.

The Eucharist celebration of Tết includes elements of Vietnamese culture and its patterns, as they are in agreement with the Gospel’s values, and can be used to show the meaning and purpose of Christian worship during the celebration of Tết. The Nairobi Statement also warns that “not everything can be integrated with Christian worship,” and “elements borrowed from local culture should always undergo critique and purification, which can be achieved through the use of biblical typology” (3.6).[8]

- Worship is counter-cultural.

The Eucharistic celebration for Tết “resists the idolatries” in Vietnamese culture, especially the practice of ancestor worship. As Romans 12:2 teaches us, Jesus Christ, the center of our faith, “came to transform all people and all cultures, and calls us not to conform to the world, but to be transformed with it.” Therefore, some components of Tết celebration, such as ancestor and idol worship, are “sinful, dehumanizing, and contradictory to the values of the Gospel.” (4.1)[9]

- Worship is cross-cultural.

The Eucharist celebration for Tết will reflect the fact that Jesus came to be the Savior of Vietnamese people and welcomes the treasures of Vietnamese culture “into the city of God” (5.1). Hymns, arts, and other elements of worship across cultural barriers could be shared to enrich the whole Church and strengthen the sense of the communio of the Church, ecumenical as well as cross-cultural, and “as a witness to the unity of the Church and the oneness of Baptism”(5.1). I hope that the Eucharist celebration for Tết and its “music, art, architecture, gestures, and postures, and other elements of different cultures” are understood and respected when they are used by churches elsewhere in the world (5.2).[10]

CONCLUSION

Faced with the struggles of second-generation Vietnamese-American Christians, as the pastor of the Morrow Vietnamese Alliance Church, I felt a need to respond to our younger members by bridging Vietnamese values and Christians values and heritage, and in so doing enabling those second-generation members to bring their whole being to church and be able to worship God in a compassionate, thoughtful, and loving way. It is crucial to recognize that the church has the responsibility to stand with individuals and families in their life crises and milestone events. I wholeheartedly agree with Greer Anne Wenh-In Ng that we should do some hard thinking about how to be the church for second-generation Vietnamese-American Christians on these issues. [11] It is recommended to contextualize other special occasions in Vietnamese-American Christians’ life cycle, such as of seventieth, eightieth, and ninetieth birthdays, of wedding anniversaries, of Vietnamese Christian wedding traditions, of Vietnamese Christian funerals and memorial services, and likewise new house or new car blessings services, business blessing services, and other special occasions.[12] Moreover, Tết Trung Thu “Mid-Autumn” or the Mooncake festival and Lễ Vu Lan – Lễ Hiếu Kính Cha Mẹ (Rite of Filial Piety – Đạo Hiếu) are two important cultural events in the Vietnamese-American religious life that are ripe for an appropriate contextualized liturgy and understanding.

All in all, I pray that God will help us carefully do our part to contextualize Vietnamese-American Christian worship and in so doing to provide worship resources to celebrate our love for Jesus the Christ, and for Vietnamese and Vietnamese-American culture. Maybe a Worship Handbook for Vietnamese-American Christian Lay Leaders and Ministers is needed in the near future. Kyrie Eleison! Christe Eleison! Lord have mercy! Christ, have mercy! Chúa ơi, xin thương xót! Đấng Christ ơi, xin thương xót chúng con!

A SUGGESTED PROGRAM FOR A EUCHARISTIC CELEBRATION OF TẾT

RESOURCES FOR FURTHER READING

Farhadian, Charles E. Christian Worship Worldwide: Expanding Horizons, Deepening Practices. Calvin Institute of Christian Worship Liturgical Studies Series. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2007.

Farhadian, Charles E. Christian Worship Worldwide: Expanding Horizons, Deepening Practices. Calvin Institute of Christian Worship Liturgical Studies Series. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2007.

Ng, David. People on the Way: Asian North Americans Discovering Christ, Culture, and Community. Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 1996.

Phan, Peter C. Vietnamese-American Catholics. Pastoral Spirituality Series. New York: Paulist Press, 2005.

Phan, Peter C. Vietnamese-American Catholics. Pastoral Spirituality Series. New York: Paulist Press, 2005.

Yee, Russell. Worship on the Way: Exploring Asian North American Christian Experience. Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 2012.

Yee, Russell. Worship on the Way: Exploring Asian North American Christian Experience. Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 2012.

NOTES

[1] Peter C. Phan, Vietnamese-American Catholics, Pastoral Spirituality Series (New York: Paulist Press, 2005), 69. In this study, I follow the US Census Bureau, which defines “generational status” as follows: the first generation refers to those who are foreign-born, the second generation refers to those with at least one foreign-born parent, and third-and-higher generation includes those with two U.S. native parents.” (US Census Bureau, “FAQ,” The United States Census Bureau, accessed January 18, 2021, https://www.census.gov/topics/population/foreign-born/about/faq.html.)

[2] Phan, Vietnamese-American Catholics, 70.

[3] Owens C. Daniel, “Genesis and the Vietnamese Story of Origins: Conversion and Cultural Identity,” Journal of Global Christianity 1, no. 1 (2015): 24–25, https://trainingleadersinternational.org/jgc/15/genesis-and-the-vietnamese-story-of-origins-conversion-and-cultural-identity.

[4] Don E. Saliers, in Upper Room Worshipbook: Music and Liturgies for Spiritual Formation, ed. Elise S. Eslinger (Nashville, TN: Upper Room Books, 2006), 33.

[5] Saliers, Upper Room Worshipbook, 33.

[6] “Calvin University,” accessed January 20, 2021, https://worship.calvin.edu/resources/resource-library/nairobi-statement-on-worship-and-culture-full-text.

[7] “Nairobi Statement on Worship and Culture Full Text,” sec. 1, accessed January 20, 2021, https://worship.calvin.edu/resources/resource-library/nairobi-statement-on-worship-and-culture-full-text.

[8] “Nairobi Statement on Worship and Culture Full Text,” sec. 3.

[9] “Nairobi Statement on Worship and Culture Full Text,” sec. 4.

[10] “Nairobi Statement on Worship and Culture Full Text,” sec. 5.

[11] Ng, “The Asian North American Community at Worship,” 163.

[12] Ng, “The Asian North American Community at Worship: Issues of Indigenization and Contextualization,” 166.