During the late spring/early summer of 2015 I found myself traveling across the state of Texas speaking to members of the five regions of the Eighth Episcopal District of the CME Church on matters of social justice. After traveling to two regions, I received a call from a former coworker who shared a chilling, but all-to-familiar, story. A former classmate of his daughter at Prairie View A&M had just been found dead in police custody. The young lady was a Prairie View Alumnus and had recently accepted a position there and had moved from Chicago back down to South Texas. Twenty-Eight-year-old Sandra Bland was at the dawn of the rest of what appeared to be a promising life.

What followed for me was a period of heightened focus on African-American women who found themselves engaged with the criminal justice system. Some suffered the indignity of public beatings while others were assaulted in the confines of central lockup. All found themselves suffering the indignity of being caged and in many cases spiraling into the abyss of darkness that is our Criminal “Justice” System. The systemic issues, the cultural insensitivity to, and the resulting challenges for women and girls who have been incarcerated all serve to rob these women of their humanity leaving them in a downward spiral of hopelessness. I contend that the Church, specifically the Black Church, is called to embody and impart the emancipatory hope needed to usher formerly-incarcerated women from the margins of despair and stand as a beacon of hope against the systemic tide of injustice.

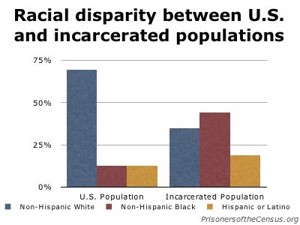

The number of women in prisons increased by 646% between the years of 1980 and 2010.[1] Th e numerical rise of women in prisons increased from 15,118 to 112,797. If we include women who are incarcerated in local, state, and federal jails today then that number climbs to 205,400. A New York Times article from September 2015 records that over 700,000 women are now incarcerated across the globe.[2] The incarceration rate is most prevalent among Black and Hispanic women. These women of color are jailed at a rate that is 43% higher than that of White women. Taken as a whole these numbers are nothing short of pandemic proportions. As the number of incarcerated women grows, so does the number of formerly-incarcerated

e numerical rise of women in prisons increased from 15,118 to 112,797. If we include women who are incarcerated in local, state, and federal jails today then that number climbs to 205,400. A New York Times article from September 2015 records that over 700,000 women are now incarcerated across the globe.[2] The incarceration rate is most prevalent among Black and Hispanic women. These women of color are jailed at a rate that is 43% higher than that of White women. Taken as a whole these numbers are nothing short of pandemic proportions. As the number of incarcerated women grows, so does the number of formerly-incarcerated

women who then suffer from a lack of proper support on the outside. Dr. Jessica Jacobson, of the Institute for Criminal Policy Research, says that “these women and girls are an extremely vulnerable and disadvantaged group”.[3] My hope is to lead the congregation into forming and supporting a ministry that offers emancipatory hope for women who are formerly incarcerated. “The concept of emancipatory hope means an expectation that dominant powers of racism, classism, sexism, and heterosexism will be toppled” and that oppressed people will “have agency in God’s vision for dismantling these powers of domination.”[4]

Ministry Context

Nestled in a hidden corner of the historic Fredrick Douglass Community in the city of Plano Texas is the one-hundred-twenty-four-year-old Christian Methodist Episcopal congregation of Hill Chapel. The congregation’s infancy is rooted in an era that was far less than a generation removed from reconstruction and whose formative years were shaped by the growing pains of the Jim Crow South. Formed and sustained by members of this African-American community who for the majority of her history was considered only three-fifths human, Hill Chapel stands as a bold and unwavering faith community leading in both worship and service to the Plano community. For over a century-and-a-quarter, congregants have found refuge from oppressive racial and political forces, developed educational opportunities, and molded community leaders by emulating the lessons of Christ that is lifted, worshipped, and praised in the humble sanctuary of Hill Chapel.

I have had the honor of serving as the pastor for Hill Chapel for the last fifteen years. Over this period, we have established a vibrant women’s ministry, Just Between Sisters, that has a thirst for engaging in the liberative work of Christ.

Project

Methods

The methods I choose to employ for the project are as follows:

- Research statistical information on incarceration and conviction rates

- Interview of local resource groups who engage in women’s ministry

- Focus Group to follow up on the ownership discussion held earlier in the term

- Women’s ministry leaders

- Red Door Pantry leader

- Several women from the church

- Survey of the congregation to gauge both the need and the commitment to develop this type of transformative ministry.

With the flood in information pouring in on the twenty-four-hour news cycle individuals are subject to becoming tone-deaf regarding information that engenders pain and anguish. Turning from information that conveys a message of defeatism or struggle can be used as a type of defense mechanism from what some perceive as a world that threatens their sanity. I choose to begin my project by researching incarceration trends and the rates of recidivism for women of color in the United States. My goal was to offer a clear and concise view of the problem that we were to address.

I am fortunate to have worked with leaders of women’s ministries on several occasions during my pastorate in Collin County. Valuable insight on the structure and content of a ministry that speaks to the lives of women who have been incarcerated was gleaned from Project Hope, a ministry of St. Andrews United Methodist Church in the city of Plano, which focuses on empowering women and single mothers to escape abusive and oppressive conditions and to move into a life of independence.

Focus groups offer an opportunity to gauge the passion for this project from both the leaders and all others who engage in the sessions. It gave me insight into the commitment and level of sacrifice the leaders were willing to embrace in designing and implementing this type of ministry while surveying the congregation allowed me to gain a better idea of the need for this ministry in our local context and to benchmark the level of commitment that the general congregation would rise to in the shaping of this type of transformative ministry.

Proposal

A layered process for equipping and enabling women to escape the bonds of hopelessness brought on by prior incarcerations is proposed. Each layer is designed to foster partnering and requires a commitment to solidarity with those whose hope it is to escape the bonds of injustice.

Fellowship & Worship

A great deal can be accomplished by leveraging resources to solidify formally-incarcerated women’s dignity in fellowship and worship. Every congregation can and should develop a clothing closet and a “pantry” of essential items.

Navigating Life

Layered on top of these resources are partnerships with governmental, civic, and private agencies that serve more specific needs. One of the leading causes for individuals being incarcerated is the lack of skill and knowledge in dealing with mental health issues. The National Alliance on Mental Illness, NAMI, is an excellent resource for locating services for those who have and those who are impacted by mental illness.

Ownership & Voice

The third layer is designed to foster ownership within individuals who have suffered the indignity of incarceration. This can be achieved through partnering with advocacy groups and by developing targeted ministry programs.

Lead Toward Solidarity

THE REV JANET WOLF | Join us for our 13th ANNUAL CONFERENCE! (theologyandpeace.com)

Without a personal attachment, this type of work can easily be viewed as an act of charity. This is unfortunate in that we can, and often do, do much harm to individuals when the church performs acts of charity as opposed to standing in solidarity. The least of which is to rob individuals of their agency. Without a sense of agency individuals are made to bow under the pressure of having to be seen as deserved of the benefits that may be gleaned from the “ministry”. To stand in solidarity is to commit to walking with each other, seeing and hearing each other, and to humble one’s self to both serve and to follow in spite of the history of the person leading. It is to see and embrace the person.

[1] Harrison P Guerino, W Sabol, “Mental Illness Surveillance Among Adults in the United States.” 2011, Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Accessed January 15, 2021, http:// www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6003a1.htm?s_cid=su6003a1_w.

[2] Emma Bracy, “More than 700,000 women and girls are in prison around The world.” New York Times. September 28, 2015, Accessed January 21, 2021, http://nytlive.nytimes.com/womenintheworld/2015/09/28/more-than-700000-women-and-girls-are-in-prison-around-the-world/.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Evelyn L. Parker, Trouble Don’t Last Always: Emancipatory Hope Among African-American Adolescents, (Cleveland: The Pilgrim Press, 2003), viii.