The Who and The What

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA)[1] comprises 65 synods, geographical territories governed by bishops. As one of those bishops, I oversee the states of Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee. I oversee 300 pastors and deacons, and we have 55,000 baptized members within 155 congregations (12 African Descent, 2 LGBTQIA+ focused, 1 Indian, 3 Latino), prison and hospital ministries, campus ministries, and outdoor ministries.

Addressing the Epidemic of Racism from the Pulpit to the Public Square

We are a storied people. Worship celebrates God’s story in preaching, singing, liturgical language, bread, wine, and water. God’s story and humanity’s story are intertwined.

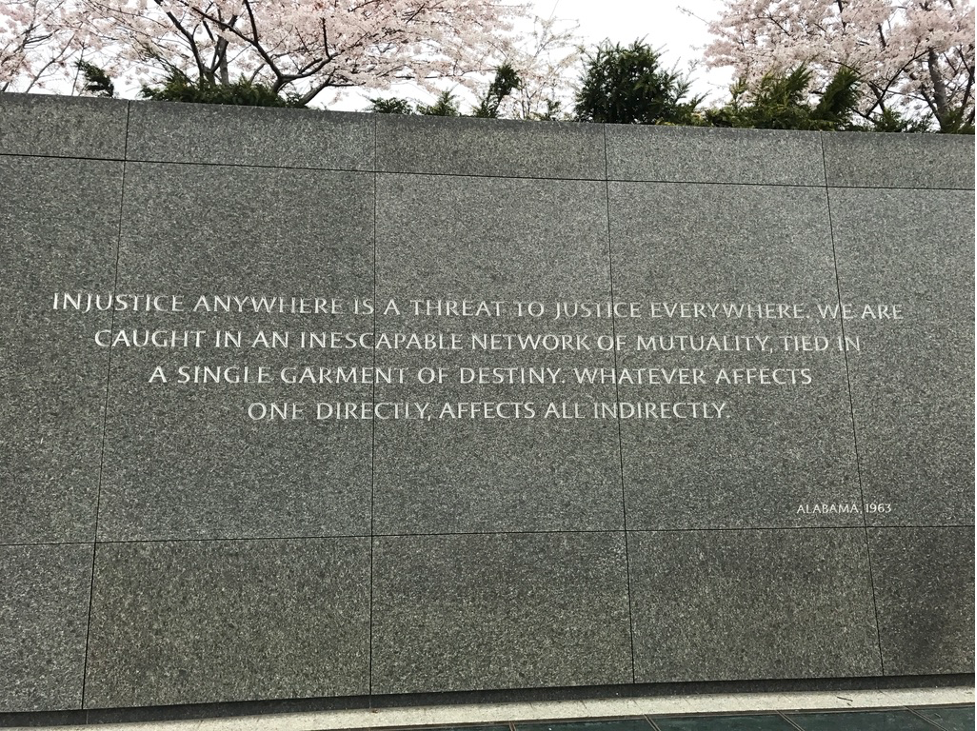

And yet, God’s story and our own have become more divided and politically partisan. This divide is most evident on Sunday mornings when the Christian assembly gathers for worship. It is as accurate today as it was when Martin Luther King, Jr. said in 1964, “Sunday mornings are the most segregated hour in America.” This racial divide is clearly evident in the majority white denomination of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, especially in the Bible Belt. The racist-rooted geography of the Deep South still springs forth within the sordid stories of the past and creates conflict.

The Church Needs to Swim into Justice’s Streams

For a denomination like the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, which has committed itself to the eradication of racism, that necessary work is not always met with optimism or a willingness from all people. The church has made many attempts to address diversity and racism, but most have been failed attempts.

As a bishop, I have negotiated over fourteen pastors out of a call over four years. Most were due to accusations of “being too political” or “being too involved in social justice work.” When I inquired more, I found out (in listening to sermons and speaking with members) that many of those preached about racism and white supremacy as a sin. Many were involved in LGBTQIA marches, gun violence rallies, and Black Lives Matter protests.

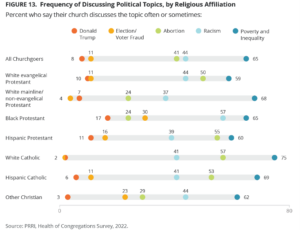

The Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), in their 2023 survey of “Religion and Congregations in a Time of Religious and Social Upheaval,” found that approximately 37% of mainline non-evangelical Protestants discuss racism within preaching or church contexts, whereas more than 57% of Black Protestants preach or discuss racism regularly.

I agree that those percentages largely represent most of the Lutherans in this area. Therefore, I set forth to address this partisan divide within our congregations, which inhibits us from living out our baptismal calling. Through three related interactions that lead to new patterns of preaching, liturgy, and conflict transformation.

Preaching: Addressing the Epidemic of Racism from the Pulpit to the Public Square

The Word of God has been used as a weapon to support racism and other corrosive “-isms” for far too long. As proclaimers of God’s vision, and not a myopic one, we must continue to preach that truth, even if it means swimming upstream. To do this well, even faithfully, we must invite the person listening to the sermon into this work, the work of scriptural engagement, the result of homiletical preparation and execution, and the follow-up after the preaching act.

Imagine with me if the preacher met each week with an interested group of church members before the preaching task and not only asked the following questions but did so by first reading the assigned text for the Sunday with an exposition of the biblical contexts and holding that in one hand with the daily news in the other. This practice will enable the preacher to have greater insight into what congregation members may deem “political,” “partisan,” or “hard topics.”

Questions to ponder:

- What does God want for us?

- Where do we find similar situations in the Bible?

- Where or how do we see the Triune God at work?

- What teachings and actions of Jesus might be helpful here?

- Where/What are signs of hope that the spirit is showing us?

- What is God calling us to do?

- What kind of Christians shall we be in light of this?[2]

Liturgy: Language that Calls Us Towards Justice

When praying, singing, and preaching, do we purposefully leave out words that could be considered political, such as white supremacy, racism, and homophobia? When there is a school shooting the previous week, do we mention the event and prayer to end gun violence? Or do we shy away from such language to avoid offending someone?

Ways of connecting liturgy with a call to action that is not partisan but offers opportunities for naming the world’s pain, which does not always have to happen in preaching, are prayers of intercession, confession, lament, hymnody, etc., following my suggestion how to prepare a congregation for the sermon each week, gathering with a worship team, liturgical season group, writing group, or even the whole church in the liturgical language crafting. Liturgy is the people’s work, and this is the most concrete way for the people to engage in that important work.

Conflict Transformation: Tearing Down Walls to Create Tables for Transformation

Fear usually prevents us from addressing conflict or misunderstanding. So, owning that fear is critical. We are surrendering to that fear or anxiety. That subversive plan is rooted in baptism; we are all submerged in its subversiveness.

I suggest using Martin Luther’s “Table Talks” model and face-to-face meetings to address conflict. Using this model:

Agenda for Table Talks

- Commit to four Sunday afternoons or evenings as a small group. At the end of the four weeks, then invite everyone to reflect on their experiences with one another. Close the time with a worship service.

- Meet for at least one hour and do so over a meal.

- Invite the African Methodist Episcopal Church neighbors to join for dinner and conversation. Start with something neutral and positive. Begin with each person’s introductions. Have each table group read the text and make sure the table groups are diverse and different. Have one person at each table be the facilitator. For instance, gathering during the season of Advent, use the assigned Old Testament reading for each meeting, read that, and offer time for group reflection:

- What did the text say to you?

- In these Advent days, what does hope look like for you?

- What do you struggle with as a pilgrim on the journey?

- When have you felt like a foreigner, alien, stranger, outcast? Those who have been far off? When have you made others feel that way?

- Close each session with prayer and song.

Conclusion: Justice Rolling like Streams. . .From the Pulpit to the Public Square

As Patrick Reyes has eloquently stated, “It’s not a matter of wanting to change the narrative; we must do the work to change it. We must create systems. The question is not about the technical changes necessary to make it happen. We need an entire mindset shift. We need a new imagination about our desired future.”[3] I believe that the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America needs to change the narrative about racism and create systems to make that possible. We need to be a church wildly engaged in an imagination that God isn’t finished with us yet and make that imagination a reality for all people.

[1] For more information on the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, see Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, “About the ELCA,” ELCA.org, accessed March 19, 2024, https://elca.org:443/About.

[2] Leah D. Schade. Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide. ( Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc., 2019). 185.

[3] Patrick B. Reyes, The Purpose Gap: Empowering Communities of Color to Find Meaning and Thrive (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2021), 178.