Spirituality in Secular Spaces: The Challenge

As religiosity shifts in our contemporary culture, the Church must shift its perspective to ensure that an orthodox but adaptive future is possible. We have an opportunity at the intersection of overt religious experiences associated with church institutions and the in-breaking of God’s Spirit in common, everyday life, the spirituality in secular spaces. How are people experiencing God’s Presence in a spiritually meaningful way, and what implications does this have for the Church’s understanding of ecclesiology?

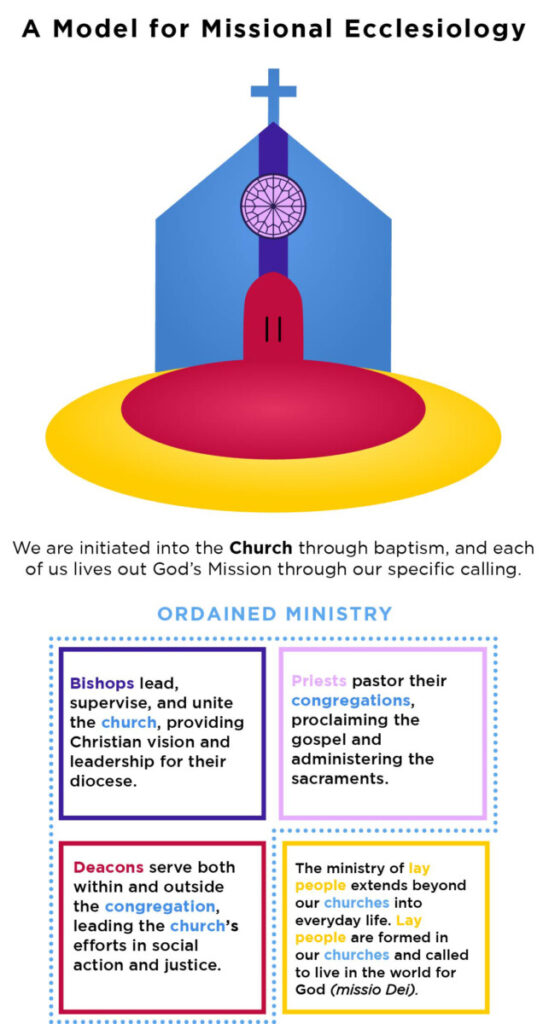

As a lay person and a Millennial, I bring a unique viewpoint to the work of ecclesiology. My research has centered on the assertion that, grounded firmly in the mission of God (missio Dei), the ministry of lay people has the capacity to bridge the gap between our increasingly declining church institutions and the robust spiritual expressions of people (particularly Millennials) outside of those institutions.

The Everyday Spirituality of Millennials

Millennials are largely unaffiliated with religious institutions,[1] though religious participation is not necessarily an indicator of spiritual engagement. As church institutions grapple with decline and aging congregations, it is imperative that the Church recognize the importance of “the language of spirituality, religiosity, and community outside the institution.”[2] The Fetzer Institute provides insight into the spiritual beliefs and practices common in the United States today, and the “How We Gather” report details how people are creating secular communities that function similarly to the historical function of churches. People are finding new ways of spiritual connection and expression that fit into contemporary lives which are less family-oriented and more focused on individual pursuits and professional achievements.

Orienting Secular Spirituality

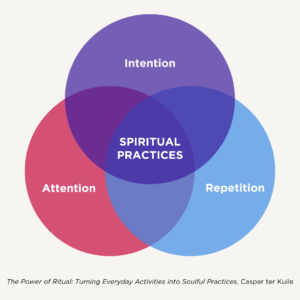

Spiritual practices and rituals are delineated by “intention, attention, and repetition.”[3] Any practice can bring us closer to God, regardless of whether it is religious or secular; it is our desire that orients our practices, and this orientation determines how we are formed by those practices. James K. A. Smith proposes that, as “fundamentally desiring creatures . . . our love is shaped, primed, and aimed by liturgical practices that take hold of our gut and aim our heart to certain ends.”[4] It is this aiming that sets the path of formation for our practices as “we are pulled by a telos that we desire.”[5] We have the capacity to utilize our habits to intentionally aim our practices so that we grow our desire for God,[6] bringing us back to the “intention, attention, and repetition” of ritual, both sacred and secular.

Spiritual practices and rituals are delineated by “intention, attention, and repetition.”[3] Any practice can bring us closer to God, regardless of whether it is religious or secular; it is our desire that orients our practices, and this orientation determines how we are formed by those practices. James K. A. Smith proposes that, as “fundamentally desiring creatures . . . our love is shaped, primed, and aimed by liturgical practices that take hold of our gut and aim our heart to certain ends.”[4] It is this aiming that sets the path of formation for our practices as “we are pulled by a telos that we desire.”[5] We have the capacity to utilize our habits to intentionally aim our practices so that we grow our desire for God,[6] bringing us back to the “intention, attention, and repetition” of ritual, both sacred and secular.

If “the telos for a Christian is to become mature in Christ (Colossians 1:28);”[7] then our aim should be to “place God at the center of your mental orientation toward life.”[8] It is critical that we examine our secular liturgies to ascertain the telos that is at their center; God’s Kingdom is not found locked up in a church building but out in the world, in God’s creation.

missio Dei as telos for God’s People

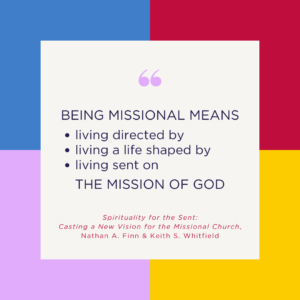

Mission does not exist as a work of the Church; rather, it is God’s work that the Church is invited to participate in and is sent into the world to do. If humans are desiring creatures, pulled by a telos which orients our habits and practices, then Christians must focus on God’s mission with intention, attention, and repetition, allowing missio Dei to be the telos for one’s habits and actions.

Mission does not exist as a work of the Church; rather, it is God’s work that the Church is invited to participate in and is sent into the world to do. If humans are desiring creatures, pulled by a telos which orients our habits and practices, then Christians must focus on God’s mission with intention, attention, and repetition, allowing missio Dei to be the telos for one’s habits and actions.

Spirituality in secular spaces is by its very nature contextual; our best resource to engage this mission field may be the people in our churches who are already participating in these communities organically – the laity. That said, many Christians might not explicitly understand their role in God’s mission; they might not draw the connection between their faith and these activities, so they fail to recognize their actions as motivated by their beliefs.[9] It’s as though they have lost any sense of telos in their actions, which demonstrates the clear need for lay formation.

Decluttering as Spiritual Practice: A Case Study

Lindsey Hardegree and Marie Kondo

My personal experience as a professional organizer using Marie Kondo’s decluttering method provided a case study for secular spiritual practice. I interviewed six of my fellow Certified KonMari® Consultants about their experiences to identify what (if anything) about the work of decluttering is spiritually meaningful. Two-thirds of the interviewees named that God is at work in their relationships with clients. While the telos of decluttering practices might not inherently point towards God, the intention of these specific practitioners indicates that they are “plac[ing] God at the center of [their] mental orientation,”[10] thus reorienting spirituality in secular spaces to engage with others[11] missionally. These practitioners intentionally attune their understanding of a secular practice towards God and embody practices of missio Dei in their everyday lives.

Innovating Pedagogy for Lay Formation

Definitions provided by An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church and the Association for Episcopal Deacons.

I developed a pedagogical curriculum designed to equip lay people to engage in the spiritually rich spaces in their own lives which lie outside the church. The curriculum aims to foster a deeper awareness of God’s Presence and a sense of purpose rooted in missio Dei by helping lay participants connect their faith to their everyday life through habits, routines, and intentional practices. Participants identify the secular spaces and practices in their own lives that are spiritually meaningful and discern the telos of those activities along the way.

I conducted a limited pilot of this curriculum, “Encountering the Holy Spirit in Everyday Life,” as a five-week Lenten series at the Cathedral of St. Philip. At the conclusion of the pilot, participants more clearly articulated areas of personal spirituality outside of the church, indicated a more robust understanding of purpose or calling, and identified existing habits and activities where they might live into missio Dei.

Next steps will be to further develop this curriculum to utilize a cohort-based approach which would convene space for lay people undertaking this effort. Formation in community provides opportunity for collaboration (and commiseration) around shared experiences of intentionally living missio Dei where people experience spirituality in secular spaces.

Lindsey E. Hardegree (she/her) is a seasoned nonprofit professional and is passionate about lay ministry. Interested in continuing the conversation?

Footnotes

[1] I leaned heavily on the National Study of Youth and Religion (NSYR), a 10-year longitudinal study led by sociologist Christian Smith. See Christian Smith, Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); Melinda Lundquist Denton, Back-Pocket God: Religion and Spirituality in the Lives of Emerging Adults (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2020).

[2] Terry Shoemaker, Rachel Schneider, and Xochitl Alvizo, eds., The Emerging Church, Millennials, and Religion: Curations and Durations, vol. 2 (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2022), 166.

[3] Casper ter Kuile, The Power of Ritual: Turning Everyday Activities into Soulful Practices (New York: HarperOne, 2021), 25–26.

[4] James K. A. Smith, Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation, Cultural Liturgies 1 (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2009), 40.

[5] Smith, 54.

[6] Smith, 71.

[7] Roger Helland and Leonard Hjalmarson, Missional Spirituality: Embodying God’s Love from the Inside Out (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2011), 94.

[8] Helland and Hjalmarson, 136.

[9] Charles Mathewes, A Theology of Public Life (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 9.

[10] Helland and Hjalmarson, Missional Spirituality, 136.

[11] Mathewes, A Theology of Public Life, 145.