The United Methodist Church (UMC) identifies itself as a connectional church. On one hand, it certainly is connectional, as reflected in the church’s episcopal governance, clergy appointment system, and congregational oversight structure. However, connectionalism also remains one of the most underutilized strengths of the UMC. While the appointment system can strengthen the discernment process for pastoral assignments, it can as easily foster a culture of competition, too.

Meanwhile, many United Methodist congregations have been struggling in recent years. Churches are consistently shrinking in both size and financial stability, and a decline throughout the global COVID-19 pandemic and the recent wave of local church disaffiliations have only accelerated the challenge. As a newly projected district superintendent of the UMC, this trend raises many strategic questions. Under these circumstances, collaboration is no longer optional; rather, it seems inevitable for United Methodist congregations. The question is not whether we will work together, but how we will do that. This research aims to examine the characteristics of effective cooperative parish models in the United Methodist context, and to suggest potential ways to successfully implement them.

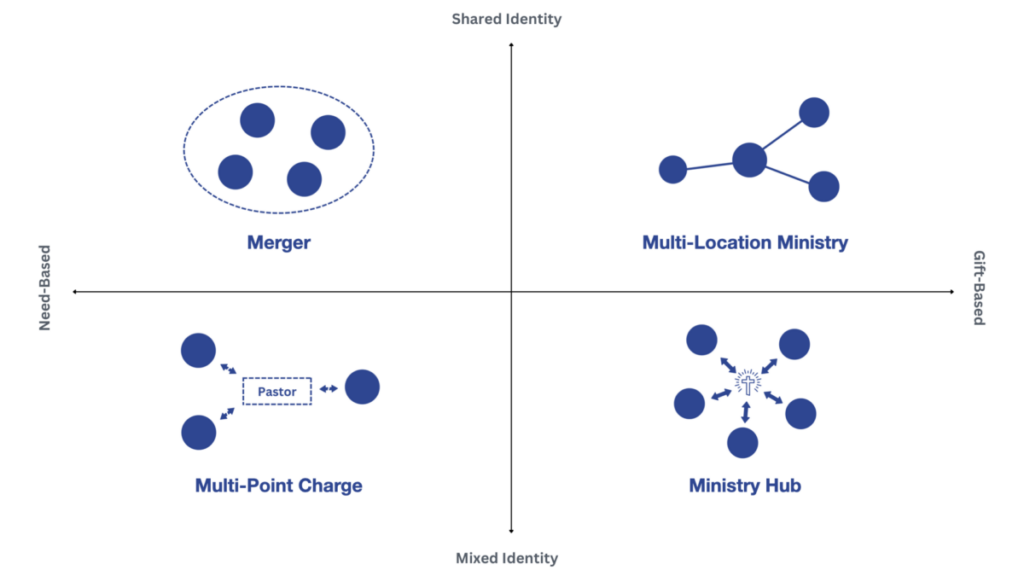

A Quadrant Study of Cooperative Parishes

The Book of Discipline of the United Methodist Church (BOD) outlines the definition and various types of the ministry in cooperation.[1] In addition to the BOD, prior studies on the subject present an expansive list of potential models for congregations to consider as they discern the path toward cooperative ministry.

When engaging in this discernment process, considering two key factors can provide meaningful insights: (a) how each congregation’s identity is defined, and (b) the motivation behind the partnership. Some cooperative parishes merge their identities under one name, while others maintain distinct identities while pursuing shared goals. Also, cooperation often arises from need—whether driven by desperation or the desire for a broader community. But it can also take a strengths-based approach, asking what can be shared rather than what is lacking. These motivations shape how congregations can work together, and the currently explored models of cooperative parish, both in the BOD and other related studies, can be broadly compiled into four categories: (1) Merger, (2) Multi-Location Ministry, (3) Multi-Point Charge, and (4) Ministry Hub.

MODEL 1: Merger

Studies suggest that mergers or multi-location ministries do not fit the traditional model of a cooperative parish.[2] While that is technically true, creatively designed mergers can also be a form of cooperative parish, when congregations facing shared needs unite under one identity. Though merger is typically seen as a last resort for struggling congregations—frequently triggering resistance, especially when one church dissolves into another—throughout merger, churches can purposefully combine their resources, properties, and mission.

However, case studies show mergers can spark healthy innovation when driven by a shared sense of purpose rather than mere survival. Most mergers are implemented as a means to prolong the congregation’s weakened heartbeat, in other words as an “ICU merger.”[3] Yet it is when churches take time for thoughtful discernment that merger can mark the birth of new ministry rather than the preservation of a fading one.

Common Table Church offers an excellent example of such a pathway: one congregation had a building but struggled with outreach, while another had growing ministry but lacked space. Their merger created a vibrant new community. With mission-driven clarity and careful attention to relationships, mergers can unlock untapped opportunities for growth and renewal.

(Video created by the Virginia Annual Conference of the UMC)

MODEL 2: Multi-Location Ministry

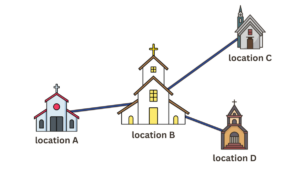

Multi-location ministry offers another expression of cooperative parish, when the participating congregations have willingness to pool gifts and resources, while operating across different sites under one shared identity.

Nett United Methodist Church in Georgia exemplifies a fresh approach to multi-location ministry. Traditionally, multi-location ministry is a byproduct of large-membership congregations, especially as a result of satellite campuses. Nett, however, focuses on community diversity and collective outreach, consciously avoiding hierarchical structures. Without having a ‘central location,’ each of its four sites within the same county serves its neighborhood in unique ways while remaining committed to shared goals. This model creates both strong local roots and unified mission work, which aligns with the church’s initial purpose to start a ministry of diversity.

(Video created by Nett Church)

Successful cooperation within multi-location ministry requires intentional equality, as imbalances can easily turn partnerships into top-down relationships. When a shared purpose is emphasized over individual contributions from each location, the ministry’s impact can multiply.

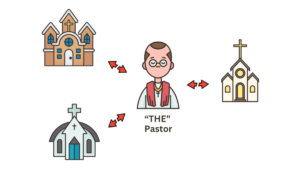

MODEL 3: Multi-Point Charge

Within the UMC, multi-point charges represent the most common form of cooperative parish. This model groups churches, often with financial constraints, under one pastoral leader, allowing them to share clergy without fully merging identities. Churches usually maintain separate names, budgets, and missions, with the pastor being the primary link between them. Given such characteristics, multi-point charges are especially common in rural areas.

Case studies for this research offered valuable insights into both the challenges and opportunities of this model. Sociologically, multi-point charge helps expand a congregation’s definition of community, shifting focus from local competition to broader collaboration.[4] However, while these arrangements often provide an immediate solution for the appointment issues, they rarely lead to long-term revitalization.[5] Clergy burnout is a major risk, as pastors often carry the full weight of maintaining unity. Leaders emphasize that success in this model requires redefining the pastor’s role as a facilitator, not a sole operator, supported by both congregations and denominational leadership.[6]

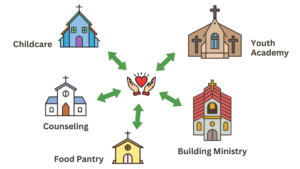

MODEL 4: Ministry Hub

The fourth model emphasizes collaboration through the sharing of unique strengths while maintaining individual congregational identities—a concept much like the “commons” in society, where resources are pooled for mutual benefit.[7] In the UMC, this model is often called ministry hub. When churches have their distinct gifts and commit to sharing them for a greater purpose, ministry hub can offer an effective means for cooperation.

This model reflects Paul’s “one body, many parts” metaphor from 1 Corinthians 12, allowing each church to focus on what it does best while contributing to a shared mission. By avoiding duplicated efforts, ministry hubs create healthy ecosystems for growth. Being underutilized yet highly promising, the ministry hub offers UMC churches a path for sustainable collaboration. Like the Stone Soup story—in which a group of hungry pilgrims cleverly persuade villagers to share their hidden ingredients by claiming to make soup from just a stone—each church’s modest gifts can combine to nourish the whole community throughout the cooperative ministry hub.

Looking Forward

Cooperative parish, when planned and implemented with clear, mission-driven purpose in accordance with the context of participating congregations, can be a fresh and effective expression of contemporary ecclesiology. To that end, several considerations warrant further discussion. First, current clergy evaluations in the UMC rely too heavily on quantitative metrics, often overlooking deeper markers of ministry vitality. This can discourage church leaders from pursuing innovative paths, including attempts for cooperative parish. Second, strategic appointment-making is another key factor for successful cooperation. Since these models involve shared vision across multiple congregations, team-based appointments can be a good consideration. Third, denominational support for part-time or bi-vocational clergy is also crucial. Some cooperation models will naturally engage less-than-full-time pastoral leadership.

Ultimately, cooperative parish is an evolving model that demands intentional design, honest dialogue, and adaptive leadership. Especially in the context of the UMC, where connectionalism is both a defining principle and untapped potential, creative application of cooperative parish models is not only prudent but imperative.

[1] The Book of Discipline of the United Methodist Church, 2020/2024 (Nashville: United Methodist Publishing House, 2024), ¶206.2.

[2] Kay L. Kotan and Jason C. Stanley, An Effective Approach to Cooperative Parishes: A Congregational Guide to Discernment and Implementation (Knoxville: Market Square Books, 2022), 15-16.

[3] Jim Tomberlin and Warren Bird, Better Together: Making Church Mergers Work (Jossey-Bass, Hoboken: 2012), 12, 31-32.

[4] Marvin T. Judy, The Cooperative Parish in Nonmetropolitan Areas (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1967), 31-33.

[5] Kay L. Kotan, personal coaching session with the author, November 25, 2024.

[6] Angela Rotherham, interview with the author, November 20, 2024.

[7] Jay Walljasper, All That We Share: A Field Guide to the Commons (New York: The New Press, 2010), 2-3.