The human cadaver has different meanings based on context, and these meanings dictate differential treatment of the cadaver. How has this phenomenon manifested throughout history?

Classical Era

Post-mortem dissection is used to understand the human body. Yet, the practice was scarce in the second century C.E because it was considered a taboo; many feared that it would mar the body. As a result, those who still wanted to understand anatomy and physiology–without compromising the corpse’s integrity–resorted to animal dissections. Galen of Pergamum, a Greek philosopher and physician, often used primate cadavers in his studies. Obviously, primate anatomy is not equivalent to human anatomy, so we cannot take all of Galen’s conclusions at face value. Nevertheless, Galen’s vast array of works were passed on as truth.

Renaissance

The Renaissance was a time of intellectual curiosity and revisiting antiquity; many of Galen’s works resurfaced. Art was also on the rise, so it should not come as a surprise that Renaissance ideals affected perceptions of the body. Thus, many felt that the value of the corpse was not in its untouched preservation; instead, the corpse’s value was its potential for beauty and discovery.

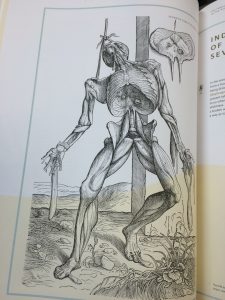

Anatomist Andreas Vesalius channeled these dualistic Renaissance values by meshing art and science together to make comprehensive anatomical textbook de Humani corporis Fabrica libri septum. In Latin, his text outlines the mechanics and placement of organs (including some of Galen’s missteps). Paired with the descriptions are detailed images of flayed corpses with toned muscles, and nature scenery in the backdrop. Often, the full corpses’ poses represent allegories. Vesalius is credited with creating a more holistic, accurate portrayal of the human body, but I believe he is also responsible for altering perceptions of the corpse. Vesalius proved that the body was functional but also beautiful. These pictures showcase the cadaver as a masterpiece brimming with vitality that one can admire with awe and reverence.

Present

Do these perceptions still hold true today? One can argue that the Body World exhibit displays cadavers in order to educate and fascinate guests. On the other hand, open casket viewings simply depict the corpse in its finest form, as if still alive. For current medical students, the corpse is a learning opportunity: human cadavers serve as excellent teaching tools for practicing sutures, exploring anatomy, and adjusting to death’s presence.

We ascribe values to the cadaver that are relative to our environments, but often we are influenced by our past. Will these values change? If so, what will they be? Only time will tell.

References:

Galen. Charles Singer, trans. Galen: On Anatomical Procedures. London: Oxford University Press, 1956.

Garrison, Fielding H. Principles of Anatomic Illustration Before Vesalius: An Inquiry into the Rationale of Artistic Anatomy. New York: Paul B. Hoeber, Inc., 1926.

Robecht Van Hee, ed. Art of Vesalius. Antwerp: Garant Publishers, 2014.

Sigerist, Henry E. “The Foundation of Human Anatomy in the Renaissance.” Sigma Xi Quarterly 22.1 (1934): 8–12. Web 9 Feb 2017. JSTOR.