In New York City, a photographer named Brandon has made a career of photographing people in the streets, recording their story, and posting them together on Facebook. Started in 2010, his Humans of New York Facebook page has since accumulated over 15 million followers and garnered international fame. His candid photographs and either concise or multi-part stories reveal intimate stories to the public, connect individuals all over the world, and create a beautiful network of strangers related only by a common humanity.

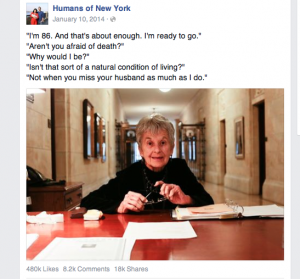

Stories portray a range of human experiences- the joys of falling in love, the losses of family members during wars and genocides, the violence in poor neighborhoods, and moments of personal struggle, defeat and successes that will trigger tears in crowded coffeeshops, laughter in silent libraries, and long reflection during the busiest of days. Among the most poignant of stories are the ones revolving around death and dying. One recent post depicts a woman whose spirited smile defies her 86 years of age.

Although the photographer emphasizes that the fear of death seems to be a human universal, she denies sharing this feeling. Her matter of fact assertion that she does not fear death is attributed to her longing for her husband. Does this woman believe death will reconnect them in the afterlife? Or does the sheer pain of life without him cause her to forsake life itself? Regardless of her reasoning, the yearning for her husband is powerful enough to neutralize a fear so intense it is referred to as “a natural condition of living”, and readers are left with heart wrenching empathy for this woman’s literally undying love and loss of her husband.

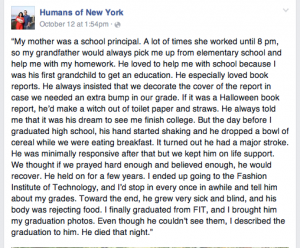

Other stories touch on the spiritual.

A young woman describes the close relationship she had with her grandfather- a man who deeply valued education. He suffered a major stroke and remained on life support, while his granddaughter went on to college. Her descriptions of the college graduation at his bedside preceeded his death later that night. Whether an eerie coincidence or a divine sign, the news of his granddaughter’s academic successes seemed to provide him with a sense of completion and finality- allowing him to pass from this life to whatever lay ahead.

Stories like these go on for pages. While their faces represent the full range of physical diversity, their words are identical in candor and intimacy. Why are these people so willing to share such tragic, uplifting, and intensely personal moments of their lives with millions of strangers? Is there something inherently palliative about confiding in others? Perhaps the social dialogue revolving around death is a way for us to cope with the dread it invokes. By addressing death, we lessen its power. The thoughts and narratives on platforms like Humans of New York provide vital outlets for survivors to share the burdens of tragedy. By sharing their stories and forming connections, people around the globe are healing from the wounds of mortality.