A traditional Western European plague doctor; they were hired en masse during the “Black Death” epidemic. Retrieved from http://www.themiddleages.net/plague.html

Death is an omnipotent force, inescapable and looming. For this reason, it has been quite often referred to as the “Great Equalizer.” This designation masks the inequality of death as a culturally constructed process affected by social power dynamics. A quintessential case in the regard is the relationship between African-Americans in the United States and death.

The social oppression of individuals of African descent in the United States has been subject to scrutiny since the inception of American slavery, a “peculiar institution,” according to Frederick Douglass via his published autobiography (1845). Hence, we know that there is no facet of African-American culture that remains unaffected by the history of racism and prejudice in the United States. The experience of death is no different.

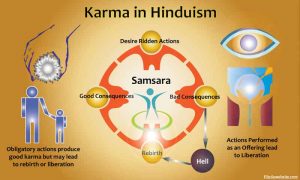

For African-Americans (and perhaps other marginalized groups) death remains a queer dyad, consisting of the social death in addition to the physical death. The concept of social death was originally described by Orlando Patterson in Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (1982) where he argued that the dehumanization of enslaved Africans related to the enforced erasure of their culture and deprivation of what are now more widely considered universal human rights constructed a slave as a “socially dead person.” He writes: “Alienated from all “rights” or claims of birth, he [the slave] ceased to belong in his own right to any legitimate social order.” In other words, an individual who does not possess capacities that are conventionally seen as common to all living humans cannot be rightfully considered to be alive in the typical sense. This state of existence can, and should, be applied contemporarily to African-Americans who still do not have equitable access to fundamental resources such as housing, education, healthcare, and education. It should also be noted that physical death rates between Blacks and whites in the United States are also still unequal (Payne & Freeman, 2006). The realization of the tension African-Americans may feel between the social death and physical death can be seen in literature. August Wilson’s 1983 play Fences (and its 2016 film adaptation), an enduring gem of playwriting on African-American experiences, provides a stellar example of this.

Viola Davis and Denzel Washington in their roles as Rose Maxson and Troy Maxson, respectively, in the 2016 film Fences. Retrieved fromhttp://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=126195963. Taken by Joan Marcus

(**Spoiler Alert**) Though the protagonist of Fences, Troy Maxson, dies physically at the age of 62, the story told by the play is very much concerned with the social death. Frequent references to death and dying throughout the play avail readers of the characters’ relationship with the end of life. Gabriel, Troy’s younger brother, who was wounded in World War 1 causing him to have a mental disability, says of St. Peter, the Christian apostle: “[He] Ain’t got my name in the book. Don’t have to have my name. I done died and went to heaven. He got your name though. One morning St. Peter was looking at his book, marking it up for the judgment, and he let me see your name.” This is a representation of the social death Gabriel underwent, as his disability caused him to become a ward of the state, unable to make decisions for himself.

Troy, a sanitation worker, expresses his dissatisfaction with his own life several times throughout the play, illuminating his awareness of his social death. He says: “Woman . . . I do the best I can do. I come in here every Friday. I carry a sack of potatoes and a bucket of lard. You all line up at the door with your hands out. I give you the lint from my pockets. I give you my sweat and my blood. I ain’t got no tears. I done spent them[…] I go out. Make my way. Find my strength to carry me through to the next Friday. (Pause.) That’s all I got, Rose. That’s all I got to give. I can’t give nothing else.”

By characterizing tears and strength as objects external to himself, Troy positions himself here without basic characteristics of humans. This aligns with Patterson’s above definition of socially dead.

Finally, the following impassioned dialogue occurs between Troy and Rose, who are married:

“Troy: Rose, you’re not listening to me. I’m trying the best I can to explain it to you. It’s not easy for me to admit that I been standing in the same place for eighteen years.

Rose: I been standing with you! I been right here with you, Troy. I got a life too. I gave eighteen years of my life to stand in the same spot with you. Don’t you think I ever wanted other things? Don’t you think I had dreams and hopes? What about my life? What about me?”

During the exchange, which occurs following Troy’s reveal that he has impregnated another woman, both Troy and Rose lament their long unfulfilled, i.e. dead, hopes and dreams, cuing us in to the social death they have experienced as a poor African-American couple circa 1960.

Nina Simone once said, “An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.” August Wilson beautifully reflected the aberrant relationship between African-Americans and death by telling the story of the two deaths, which serve as a testament to the inequality of death.

Works Cited

DOUGLASS, F., & GARRISON, W. L. (1845). Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave. Boston: Anti-slavery Office.

PATTERSON, O. (1982). Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

PAYNE, R., & FREEMAN, H. (2006). “Racial Attitudes and Health Care Disparities in African American Communities: Historical Perspectives and Implications for End-of-Life Decision- Making” in Key Topics on End-of-Life Care for African Americans. North Carolina: Duke University

WILSON, A. (1983). Fences. New York: Plume.