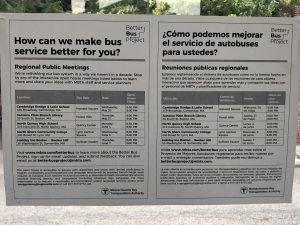

After living in New York for over a month, I can say how rich New York ethnicity is and culturally diverse it is with a vibrant mix of world influences. I am also amazed by the extensive range of cuisine available in New York. The diversity reminded me of Singapore where I grew up as it is also culturally diverse with four different cultures living together. Since English is the primary language spoken, most of the street signs are in English. Even at the Subway stations and the advertisement on the train are in English (Pictures below).

In “A contextualized approach to Linguistic” Leeman and Modan mention how “Material realizations of language are strategic tools that are wielded in local politics, power struggles, and competing claims to space” (pg 332). This is true, the fact that the United States is one of the leading and influential countries in terms of politics and business where New York is a global hub for business. The city does not need to conform its language to other foreigner languages, but foreigners will have to learn English to go around New York. However, New York is inhabited by people of different races and cultures and the dominance of English signs does not stop them from embracing their own culture. You could see it on the street where there would be people speaking in different languages from Polish to French. Even though English is prominent in its linguistic landscape in New York, the people living there makes it diverse by coming together to create their community.

New York is separated into five different boroughs: Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens and Staten Island. Each borough has its subset of culture where specific areas have a rich cultural origin. For example, in Manhattan, Harlem is a place rich in its African American and Caribbean culture. It is also the home of Jazz since I like listening to Jazz songs, this was one of the memorable places I have been to as I went to National Jazz Museum. I was surprised by how rich and explicit the culture is in that specific region.

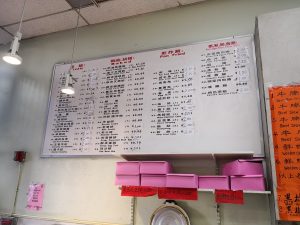

However, unlike Harlem which is in the north of the city, areas that are in the city center (Manhattan) like Chinatown and Koreatown are not culturally authentic. There is a strong influence of western influence in those regions. Restaurants that have Chinese signs would have the English translation for the tourist. These translations are similar to what Leeman and Modan said about the Chinatown in Washington DC’s, “the state and private enterprise commodify language… turn Chinatown into a commodity, marketing it and the things in it for consumption” (Pictures of Chinatown below)

The Chinatown neon sign hanging above the area in English further prove the points how it is only a place for tourist to visit. That sign is for tourist to come to take a picture of it to show the “new culture” they have explored even though there were not much cultural history in that area. Tourists only go there to try “authentic” food. Furthermore, with the English translations on Chinese restaurants and English signs in Chinatown, tourists do not get to experience the Chinese culture fully. Chinatown has been gentrified and is becoming increasingly expensive causing traditional Chinese restaurant owners to not be able to afford the rent and have to move out of Manhattan.

However, in the area at Queens, Flushing. There is still a robust Asian culture there. I could tell the difference immediately as I noticed the majority of people in Flushing were all Asian, where there was an abundance of Chinese signs and traditional stores everywhere with not as much English translation compared to Chinatown. (Pictures of Flushing below)

I remembered when I first got to Flushing. I thought I was in an Asian city. I admire how the Asian cultures are rich in Flushing and were happy that it had not been tainted with the Western influence like the Chinatown. Since most of the people were Asian, the people there mostly speaking in Asian language like Mandarin, Korean and Japanese.

New York is always changing and conforming to the influences of the world. The fact that there is limited space in the city center at Manhattan causes the process of gentrification to be faster causing some area to lose its culture turning it into the “Chinatown” of what Leeman and Modan said about Chinatown. I hope that culturally rich areas such as Harlem and Queens will be protected from the gentrification as that is what makes New York “New York”, with it being the culturally diverse city.

Sources:

Leeman, Jennifer, and Gabriella Modan. “Commodified Language in Chinatown: A Contextualized Approach to Linguistic landscape.” Journal of Sociolinguistics, vol. 13, no. 3, 2009, pp. 332–362., doi:10.1111/j.1467-9841.2009.00409.x.

Multilingual usages suddenly fulfill the street: some public signs are made by English and Korean for the local residents’ reading convenience and numerous Korean shops label their special cuisines and trade names in Korean and English to demonstrate the special culture and exotic business style. It will not take a lot of time for visitors to realize this place is relative to Korean elements. While enjoying the fresh linguistic experience, people will feel the uniqueness from this place and appreciate the language culture behind those signs. As the reading suggests(page 344, Leeman & Moden, 2009), such abundance in evocative business signs, foreign language usage, and distinct racial clustering not only satisfies government’s need of preserving and promoting foreign cultural heritage, but also distinguishes the special neighborhoods, such as Korean town, from its surrounding and indicate certain groups.

Multilingual usages suddenly fulfill the street: some public signs are made by English and Korean for the local residents’ reading convenience and numerous Korean shops label their special cuisines and trade names in Korean and English to demonstrate the special culture and exotic business style. It will not take a lot of time for visitors to realize this place is relative to Korean elements. While enjoying the fresh linguistic experience, people will feel the uniqueness from this place and appreciate the language culture behind those signs. As the reading suggests(page 344, Leeman & Moden, 2009), such abundance in evocative business signs, foreign language usage, and distinct racial clustering not only satisfies government’s need of preserving and promoting foreign cultural heritage, but also distinguishes the special neighborhoods, such as Korean town, from its surrounding and indicate certain groups.

Figure 1. An official fire safety sign

Figure 1. An official fire safety sign