San Francisco is one of the most ethnically diverse cities in America. The 1850s gold rush brought in treasure hunters both domestically and internationally, rapidly increasing the population and city development. As more urban constructions were initiated such as railroads, gold mine machinery and skyscrapers, massive amounts of labor are needed. That is when rumors about the American dream are spread to the far east. Tenths of thousands of Chinese were lured to the west coast and provided labors for the City construction. In the past 150 years, the Chinese has gathered between Bush Avenue and Telegraph Hill avenue, enclosing the Area within, and named it Chinatown. Through my humble observation over the past few weeks, I found that Chinatown has a unique Chinese culture that is different from any of other Chinese culture due to the influence of linguistic landscapes.

It is impossible to fully understand the Chinese culture without experiencing the authentic Chinese cuisines. There was a Chinese saying “名以食为天,” or in English “Hunger breeds discontentment.” The ancient Chinese believe that food is the founding stone of flourishing Chinese culture. As a result, almost half of the stores in Chinatown are grocery stores and restaurants. A few of my favorite includes the traditional Southern Chinese cuisine Dim Sum and the most well-known Central Chinese cuisine Hot Pot. It is well-known that Chinese food in Chinatown is much more authentic than those in the other places, because Chinatown restaurants serve mostly Chinese, while other Chinese restaurants target local Americans.

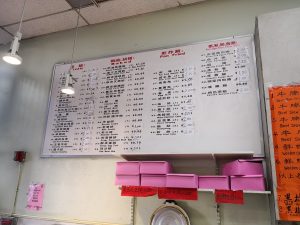

As a Chinese student, being able to live as close as one block away from Chinatown gives me a sense of security and a sense of coming home. However, while the food is more authentic and the faces around are more familiar, I found living in Chinatown almost like living in a foreign country, mostly because of the language barrier between Chinatown and the “outside world.” Early Chinese immigrants were, without exception, from Guangdong province, where the official language is Cantonese, a majorly different dialect from Mandarin. From then on, Cantonese has been the dominant language in Chinatown. Signs are written in traditional Chinese characters, and town folks bargain loudly in Cantonese. Undoubtedly Cantonese is both the official language and working language in Chinatown.

One of my favorite bilingual signs in Chinatown is the political campaign signs. Mark Leno is a California state senator who is running for the San Francisco city mayor position. Chinatown, as one of the most populated areas in the city, is extra crucial to his campaign. His campaign post transliterated his last name into two powerful characters to gain support in Chinatown. He also translated his campaign slogan to Chinese which I wasn’t able to find the original English text. Perhaps this Chinese slogan is the original text. This idea is also illustrated in Jennifer Leeman and Gabriella Modan’s article, that “material realizations of language are strategic tools that are wielded in local politics, power struggles, and competing claims to space” (Leeman and Modan 333). Overall I think this is evidence that Chinatown and Cantonese plays a significant role in San Francisco city culture

.

Other languages also play significant roles in the Chinatown community. Chinatown is a famous city attraction that draws more tourists than the golden gate bridge annually. Since English is the universal language spoken around the globe, many stores were able to communicate with the tourist in fluent English. Menus are written in both Cantonese and English, and waiters serve in both language as well. In fact, most residents in Chinatown are second-generation immigrants who were born and raised in America, where they have picked up English either in school or in daily life.

Mandarin, on the other hand, is more like an outcast language in Chinatown, even though it is much similar to Cantonese linguistically. My last experience in a Szechuan food restaurant, the waiter couldn’t communicate with me in Mandarin but instead talked back to me in English to ask me for orders. In my opinions, this is mainly because of the small mandarin speaking population in San Francisco 20 years ago. Thus, there is no need for Chinese restaurant workers to learn Mandarin to serve customers.

In comparison, San Francisco Chinatown reminds me of Hong Kong, mostly because of the language and the culture preserved. It has some of the most authentic Chinese food in town, which also draws the similarities between the two cities that are far apart. However, San Francisco Chinatown is more inclusive in terms of English speakers, while Hong Kong seems to be influenced more by the mainland mandarin language. In conclusion, this Chinatown remained a unique cultural Icon of the far east in downtown San Francisco.

Citation:

Leeman, Jennifer, and Gabriella Modan. “Commodified language in Chinatown: A contextualized approach to linguistic landscape.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 13.3. (2009).