Céline Sciamma wonderfully portrays the beauty and predestined constraints of Queer love mirrored by the Greek story of Orpheus and Eurydice. Primely signified through color dynamics and long shots to showcase the storytelling of their paralleling love tales.

The story of Orpheus and Eurydice — one that is constantly referenced throughout the film through color parallels, dialogue, behavior of the characters, and similar themeatical aspects of their love. Orpheus was a poet and musician who traveled to the underworld and back in an attempt to reclaim his wife who had passed. The white ghost-like silhouette of Héloïse is almost haunting Marianne, signifying her impending wedding and departure. While the long short panning outwards stirs up an unsettling feeling — Marianne isn’t necessarily scared of this view of Héloïse just terrified of what this image means for the longevity of their love. Orpheus was eventually granted Eurydice’s departure from the underworld after he played the most beautiful music for Hades (the Greek God of the underworld), under one condition, that he wouldn’t look back at Eurydice leaving with him until they were both out and free from the shadows of the darkness. Turning back to the film, in Marianne’s departure scene Héloïse yells out at her “Look back!” As the camera places a deep focus on Marianne’s face, as Orpheus faces, as soon as she looks back, she also knows she will never have this love again in this lifetime. It’s devastating, and just like Orpheus, she got to see Héloïse one last time, in the big white dress she had been picturing her in.

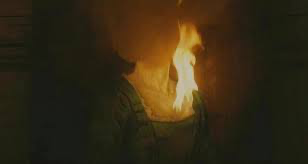

Years later, the significance of Héloïse showcasing the number 28 in the portrait of her and her daughter isn’t simply to tell Marianne that she remembers her. In my opinion, it’s to convey that no matter who paints her Marianna is the only one who actually sees her — which even is reinforced during the theater scene where Marianne sees Héloïse crying to her favorite musical piece and goes unnoticed herself. Eyes and viewing were the carrying themes in this film. For Marianne’s character, this was personified by fire. She was always dangerously close to fire, however, it seemed to be amplified the closer she got to Héloïse. Initially, it was lighting the nicotine pipe, then it was sporadically burning the old painting — perhaps out of care for Héloïse and not wanting her to be misrepresented. Finally, when Héloïse’s dress caught on fire, which we know was a significant time for the both of them because they reminisced about it during their “I’ll remember…” talk. Marianne burning that portrait of Héloïse’s beginning at the heart, symbolized her understatement of Héloïse’s character.

Lastly, Héloïse is a personified version of the female gaze this movie centers around. In a film filled with perspective shots, it follows her gaze and Mariannes subsequently. Héloïse illustrated as delicate, soft, introduced as mysterious, and innocent while Marianne is introduced as brutish — from the way she arrives at the residence. However, the scenes are what allow them to connect. Sound and background noise were almost completely voided in this film, especially during the outdoor scenes, in the silence, sometimes all they could do was stare and analyze each other. Marianne was able to understand that Héloïse was burning from the inside out from the intensity of her gaze alone.

I‘m also reading the film from the same perspective of female gaze and the way the director presents their love affairs.

In the beginning of their first meet, Heloise was introduced into the frame with black cloak covering her body and turning her back on Marianne. As the door opens in front of Heloise, exposure of light suddenly changes from low to high, with the camera following along the way as Heloise runs out. Marrianne wants to observe Heloise as she runs after, but Heloise never turns around to give her the chance. At the end, two characters exchange their positions, with Heloise standing behind and calling for Marianne at the door. Marianne turned, as opposed to Heloise’s previous unhesitating step on the way out of the door, indicating their changed relationship and emotions as well as corresponding to the myth. They finally followed the “poet’s way” of remembering their lovers through the very last glance rather than keeping them.

In the movie, we can often see very elaborate symmetrical compositions and parallel structures within the frame, which may be emphasizing the equal love relationship between the two characters. Male gaze is not only displayed through specific scripts or actions, but a lot of time through the use of levitation of spatial position of male characters. While at the beach for the first time, the two main female characters were standing side by side, with one leading in the shot one in front of the other. The director utilizes selective focus by having two focuses rather than one person blurred, implying that they are equals from the start. Upon entering the room, despite stopping at the stairs, instead of shooting one character from lower angle and the other from upper angle as in many movie perspectives, both protagonists are at the end of the stairs looking at each other horizontally. This reveals that even though “Heloise is illustrated as delicate, soft, introduced as mysterious, and innocent while Marianne is introduced as brutish”, both were presented equal status.