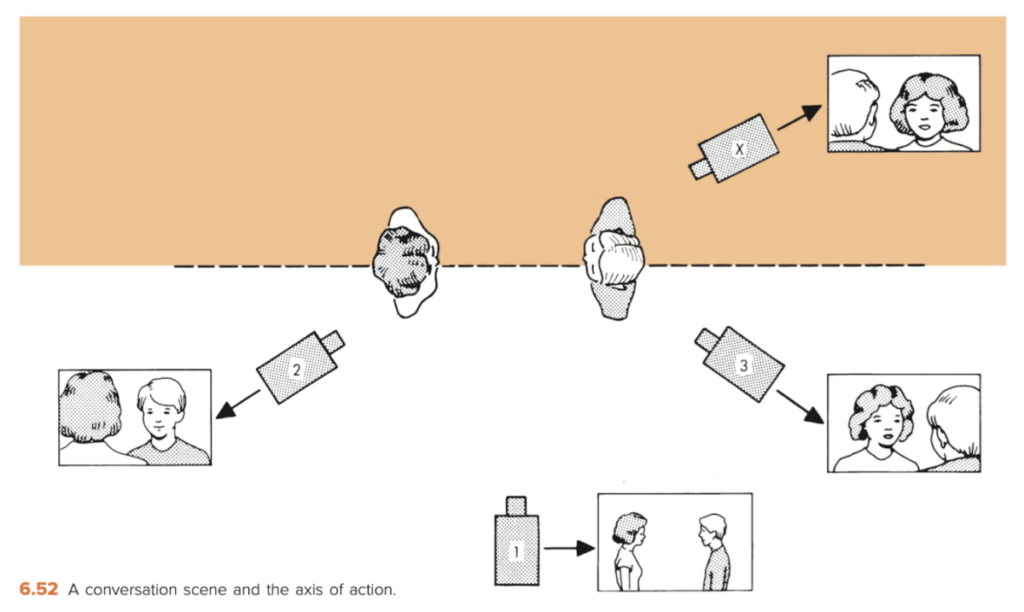

As discussed in our Film Art textbook, editing is an impactful tool that can build upon the overall form of a movie, and editing gives filmmakers a huge number of options when perfecting their project. Editing comprises of everything from the transition between shots to the manipulation of film space that the characters of a film occupy. Editing is made up of an infinite number of deliberate choices, and one concept of the chapter that caught my attention is spatial continuity and the 180 degree system, as well as the typical shots that are associated with the 180 degree system, shown in the image below. When two characters are having a conversation, for example, the scene usually establishes the relative positions of the two characters with a medium shot of the two characters in profile (1), then a shot of the first character over the second’s shoulder (2), then a shot of the second over the first’s shoulder (3).

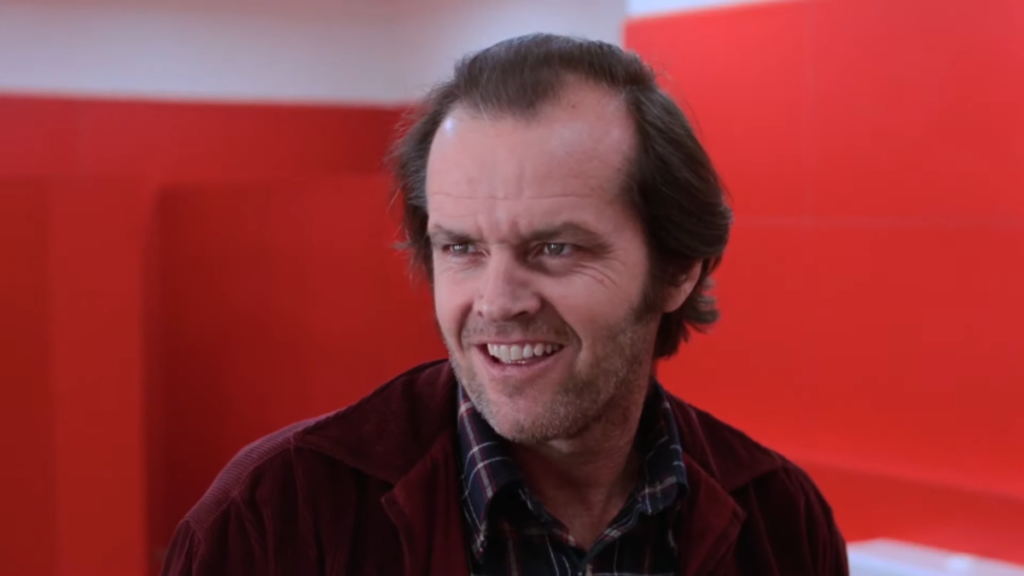

However, not every filmmaker chooses to obey this 180 degree rule, breaking up the consistency established in previous shots and instilling a sense of disorientation in the audience. One famous example is in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), when Jack is speaking to Delbert Grady in the hotel bathroom. Although we first see Jack on the left side and Grady on the right, Kubrick chooses to film them from the opposite side in the next shot, switching the positions of Jack and Grady in the shot. This violation of the 180 degree rule feels like a distortion of reality, which is appropriate for the context of the scene as Jack is experiencing a break in reality.

Another interesting use of the 180-degree rule is in Wes Anderson’s films. Anderson is famous for not only his distinctive mise-en-scene, but also his meticulous use of editing in his movies. One common way that the filmmaker edits scenes is by using rigid 90-degree or 180-degree changes between cuts, giving an artificial feel to Anderson’s movies. David Bordwell describes this type of editing as compass point editing, where the camera moves in 90 degree increments like a compass pointing in the four cardinal directions. As a result of the structure of these cuts, we usually only see either the front or back of a character or their side profile, and rarely do we see a naturalistic, three-quarters view of a character’s face. Although Anderson doesn’t necessarily violate the 180-degree rule, he distorts it and uses a very geometric, rigid approach to the rule to give his movies the quality of feeling unnatural and manufactured.