Paris is Burning (Livingston, 1990) is a documentary that showcases the livelihood, ambitions, and conflicts in the drag queen community in New York City in the late 80’s. The late 1980s was a difficult period for members of the LGBTQ community. The AIDS epidemic was roaring across the United States and was receiving little support from the federal government. The zeitgeist among the white middle class and upper class was that Gay men were the root cause of this epidemic, especially those of color. We now know that this is untrue, but homosexual men were still the most affected by HIV/AIDS. This subjugation of the LGBTQ community was likely the reason why Livingston decided to go to Harlem to document Drag Ballrooms.

Bordwell and Thompson claim that documentaries in categorical form are “designed to convey categorized information.” Unlike categorical forms, however, rhetoric form documentaries make an argument and persuade their viewer that it is correct. Furthermore, Bordwell and Thompson state that a rhetorical documentary often “presents arguments as if they were simply observations or factual conclusions.” Paris is Burning presents a main thesis: Drag Queens, Transgenders, Gays, and Bisexuals (particularly Latino and Black members of these communities) are held back because of their sexuality and race. As a result, members of this community formed Balls (ballroom competitions) to compete with each other and enjoy themselves for who they are.

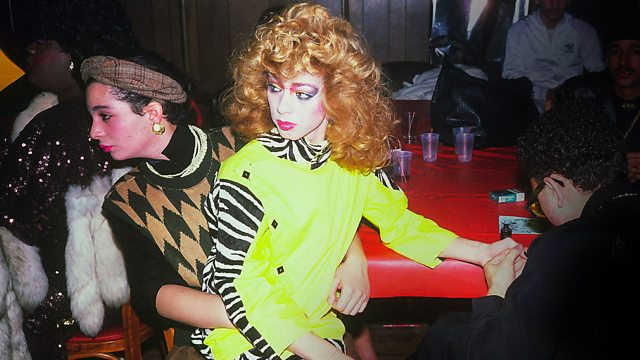

To provide evidence for her argument, Livingston documents numerous people involved in Ball culture in Harlem. For example, take Octavia St. Laurent. She didn’t popularize vogue dancing like Willi Ninja or hold a significant position of power like Pepper LaBeija. Instead, she was depicted as a normal drag queen, opening up emotionally about her hopes, dreams, and desires such as becoming a modeling star. Livingston suggests that every member of the LGBTQ community, not just Octavia, have dreams like these. Most Straight, white Americans, at this time, had a distorted view of drag queens and gay people. As such, dreams of becoming wealthy, or even comfortable were heavily inaccessible. Therefore, in balls, people expressed themselves as executives, soldiers, and high fashion Parisians to live the life that they couldn’t due to uncontrollable circumstances.

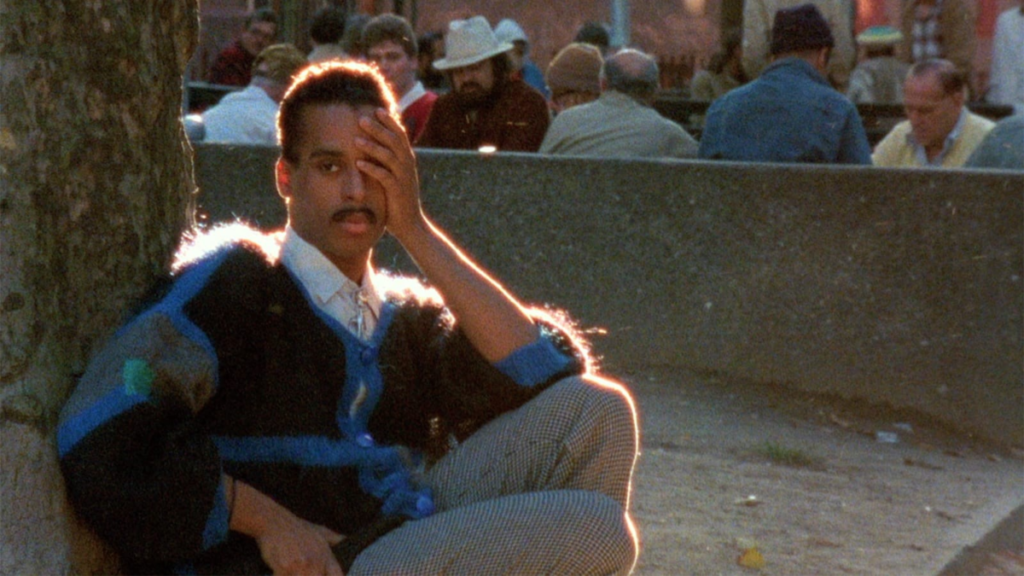

I believe that Livingston’s strategy of maneuvering her argument is intelligent. In the long run, most people are better convinced when they aren’t told what to believe, but subtly shown something that changes their belief. Therefore, it is a brilliant choice to choose Ball games as the main setting for her documentary. She films life inside and outside the ballroom. Drag queens glimmer with enjoyment inside the ballroom but are often penny-pinching on the streets of NYC. Drag queens, such as Freddie Pendavis attempt to maneuver the outside world by putting on a mask. This façade is extremely discouraging and unbearable. As a result, ballrooms were a haven for thousands as people were allowed to freely express themselves.

In conclusion, “Paris is Burning” is a convincing rhetorical depiction of the challenges, hopes, and resiliency of the New York City drag queen community in the late 1980s. The director, Jennie Livingston makes a strong case for the systemic difficulties that members of the LGBTQ community, especially those who belong to oppressed racial and ethnic groups, experience by highlighting the ballroom culture of Harlem. She shows us evidence, rather than telling us blatantly. The film emphasizes the common human need for self-expression, acceptance, and acknowledgment by skillfully presenting the life stories of drag queens like Octavia St. Laurent and Freddie Pendavis.

Hey Luke, you mentioned the idea that the film emphasizes on the common human need for acceptance. I agree. The film highlights the idea of “chosen families” within the house system, where LGBTQ+ individuals form bonds and create support systems as alternatives to traditional family structures. This demonstrates the human need for connection and acceptance from those we consider family. Paris Dupree elaborates that when a person has rejection from thier mother or father, they search else where to fill that void. Dupreee has personally experienced kids come to him and “latch” onto him like if they were their mother or father because they feel like they can talk to him. They feel like they have a connection and get them unlike others that have rejected them.

Luke, this is a great analysis. I agree that Livingston’s decision to show the viewers the Ball culture, rather than tell it, further emphasizes the importance of the ball culture throughout the film. The film explores the dual lives of the drag queen both within the ballroom and within New York City as a whole. Inside the ballroom, drag queens are able to openly express themselves, without the direct oppression of the outside world. However, in the broader context of the city, they are unable to truly express themselves. This contrast illustrates the disparity between the enjoyment and freedom felt in the ballroom and the challenges faced in their everyday lives. I also agree with your point that Freddie Pendavis puts on a mask in order to “hide” from reality and conceal the drag persona. The mental and emotional strain it takes on them to display a different image to the outside world, unable to reveal their true self, is discouraging and unsettling. Furthermore, ballrooms provide individuals with the freedom to reveal themselves without the fear of judgment and discrimination. This further emphasizes the significance of the ballroom culture for the LGBTQ+ community. The ballrooms are depicted as “safe spaces” where people can escape societal pressures and instead freely express themselves.

Hi Luke, I agree that this documentary is a rhetorical film because it was obvious what the director was trying to present to the viewers without explicitly saying it. I also thought that this was an effective method, especially because the film mentions societally controversial ideas like about the drag and LGBTQ community during a time of the AIDS/HIV crisis. However, I think that while the film does highlight all of the things that you mentioned, I also think that it did a lot more harm than anticipated. Part of it I think stems from Livingstons lack of payment towards the people who are presented. Pepper LaBeija said, “We didn’t read them, because we wanted the attention. We loved being filmed. Later, when she did the interviews, she gave us a couple hundred dollars. But she told us that when the film came out we would be all right. There would be more coming” (NYT). This coupled with the critique from the outsiders who just did not agree with the films argument made the film controversial, but essential.

Hi Luke,

I agree that Livingston’s strategy of maneuvering her argument is intelligent. I think the way that Livingston decided to compare life during the balls versus in their apartments is very interesting, because it shows that despite their struggles, they used these balls as a way to connect with their community and find joy in their lives. I think this idea connects to the theme of identity and self-expression, because many of the drag queens dreamed of being wealthy and living a different lifestyle. Essentially, they wanted to become the characters they were portraying within the balls, and they wanted to be perceived in that way. However, similar to your point, outside of the ballroom, this community faced immense struggle and scrutiny from others that made this lifestyle unrealistic and difficult to achieve.