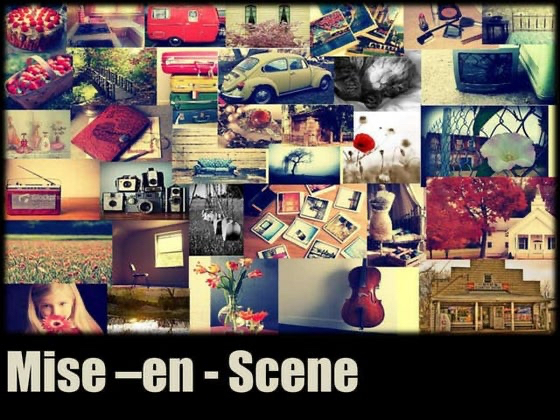

Chapter 4 of Film Art: An Introduction delves into the captivating world of mise-en-scène, a French term meaning “putting into the scene.” Originally used to describe the art of directing plays, it has since evolved to encompass the director’s control over every visual element in film. From the setting and lighting to costumes, makeup, staging, and performance, mise-en-scène is the key to creating a film’s visual language and emotional depth.

At its core, mise-en-scène is the art of making each shot not just visually stunning, but also narratively rich. Though dialogue is a key element in filmmaking, every detail, from a character’s clothing to the shadows cast on the walls, tells a story before a single word is spoken. For instance, how do makeup and costumes reveal a character’s identity or role? As actor Harrison Ford insightfully remarked, “The costume is a very important thing. It speaks before you do. You know what you’re looking at. You get a reference and it gives context about the other characters and their relationships.”

This idea shines through in D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, where the protagonist’s shabby dress is decorated with cotton “ermine” dotted with soot. This single visual cue communicates both her desire for elegance and the harsh reality of her poverty. It’s a small detail, but one that speaks volumes about her character and circumstances.

Another iconic example is Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. The Overlook Hotel’s eerie, symmetrical hallways and unsettling atmosphere communicate the film’s psychological horror visually, even before the characters begin their descent into madness. The cold, vast rooms and unnatural lighting trap the viewer in a sense of isolation, amplifying the dread Jack Torrance experiences. Here, mise-en-scène conveys the emotional weight of the story far more powerfully than dialogue ever could.

But how do filmmakers ensure that viewers notice these crucial details? As discussed in Chapter 2, audiences naturally blend what they see and hear into a cohesive whole. A study by psychologist Tim Smith, using eye-tracking technology, revealed that people’s gaze tends to focus on essential storytelling elements, such as faces, gestures, and the speaker in a shot. Filmmakers use mise-en-scène to subtly guide viewers’ attention, helping them follow the story’s emotions and themes by emphasizing key visual components.

Mise-en-scène—the combination of settings, lighting, costumes, and performance—acts as a vital part of storytelling in film. These visual elements stir curiosity, suspense, and surprise, often becoming motifs that recur throughout the story. Even the smallest decisions, like a flicker of light, or a subtle gesture, can deeply affect how the audience connects with the narrative. Whether by instinct or careful design, filmmakers use mise-en-scène to engage and captivate viewers, showing how much power lies in the visual elements of cinema.

One of my favorite examples of mise-en-scéne is the use of color. I find that color holds so much storytelling ability just through how it is used in a scene due to the emotions that humans have placed onto them. For example, red can represent passion, energy, love, etc., while purple may represent royalty, luxury, wealth, etc. What colors represent can be broad as well, which can allow viewers to have multiple differing perspectives on a film. For example, blue can be associated with sadness, but it can also be associated with professionalism. Color also has the ability to contrast two characters to enhance the story. If a character is wearing black and the other character is wearing white, there is clear, unspoken tension between the two.

I find that color, alongside other visual elements are some of the most impactful ways to tell a story, sometimes more than the script itself.

After watching “The Grand Budapest Hotel” the argument for the narrative power of Mise-en-scène as a guide to the viewer rings particularly true. For example when we are first introduced to the hotels interior, while behind the concierge at his desk, the Boy With Apple painting’s immense detail contrasted with the solid colored walls on which its hung draws the viewers attention. Once we learn the significance of this art piece as a priceless piece of a contested inheritance, it leaves Madame D wall with the protagonists and takes on a persona of its own. The intentional presence of the painting, or lack thereof, develops the plot of the story and mirrors characters actions. When Agatha is dangling off of the building the painting hangs directly above her and its concealed letter is central in the shot. As the narrative returns to the present, where the painting is but a decoration, the significance of the object and its place in the hotel is only furthered once we learn that Zero, the hotels current owner, is the only surviving character from the story of the paintings heist. Wes Anderson masterfully uses Mise-en-scène with the placement of Boy With Apple to guide the viewer through the structure of his story.