The article “All That mise en scène Allows: Douglas Sirk’s Expressive Use of Gesture” delves deeply into Sirk’s mastery of subtle, often overlooked aspects of performance, such as the gestures of the characters. It argues that these small, often overlooked movements play a pivotal role in conveying the emotional tension in his films, particularly in All That Heaven Allows (1955), where Cary (Jane Wyman) navigates her romantic feelings for Ron (Rock Hudson) under the weight of societal pressures.

What makes this piece particularly compelling is its focus on the physicality of performances, a contrast to the usual analysis of Sirk’s use of color and camerawork. The article shows how restrained gestures and set design work together to mirror the characters’ inner struggles, as well as the confining social environment they inhabit. Through the decoding of these layers of movement, the article demonstrates how Sirk transforms mise-en-scène into an emotional landscape, allowing readers to appreciate the film’s intricate choreography of gestures and body language. This approach provides a fresh perspective on a film that has been examined from numerous other angles.

The true strength of the article lies in its ability to combine film theory with practical analysis. It goes beyond a superficial appreciation of Sirk’s visual style to explore the technical aspects of mise-en-scène, including how lighting, blocking, and set design collaborate with the actors’ movements to generate emotionally charged moments.

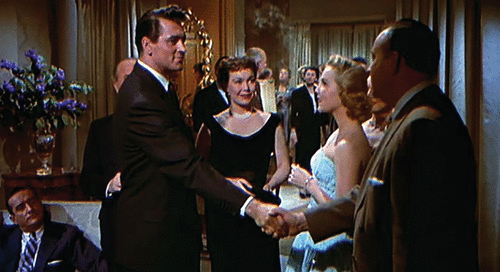

Sirk’s use of focus is particularly noteworthy, especially his employment of deep focus to shape the audience’s emotional experience. This technique emphasizes Cary’s upper-middle-class environment, capturing every detail of the world that suffocates her. By keeping the entire scene in sharp focus, Sirk reinforces the idea that Cary is constantly surrounded by the judgmental gaze of societal expectations, turning her physical surroundings into a metaphor for the emotional prison she cannot escape, hemmed in by the demands of respectability and appearance.

Sirk’s meticulous blocking also communicates power dynamics and emotional distance. For instance, in scenes between Cary and her children, he frequently positions her in isolation within the frame, emphasizing the generational and emotional gap between them. In contrast, Ron’s placement in the frame often suggests emotional closeness, signaling his role as Cary’s escape from the rigid societal norms she struggles with.

Ultimately, the article showcases Sirk’s mastery of mise-en-scène, where gesture and physicality take center stage in conveying emotion. It leaves us to wonder: In All That Heaven Allows, are the characters’ restrained gestures a true reflection of their inner feelings, or do they emerge in response to the suffocating social pressures that surround them?