One of the most fascinating forms of film that is, in my opinion, not talked about enough in film academia is animation. When the average movie-goer is confronted with animation in film, they generally relegate it as an artform that caters to children and their entertainment. But animation is a powerful medium whose influence transcends the cute kiddie Saturday morning cartoons of our yesteryears.

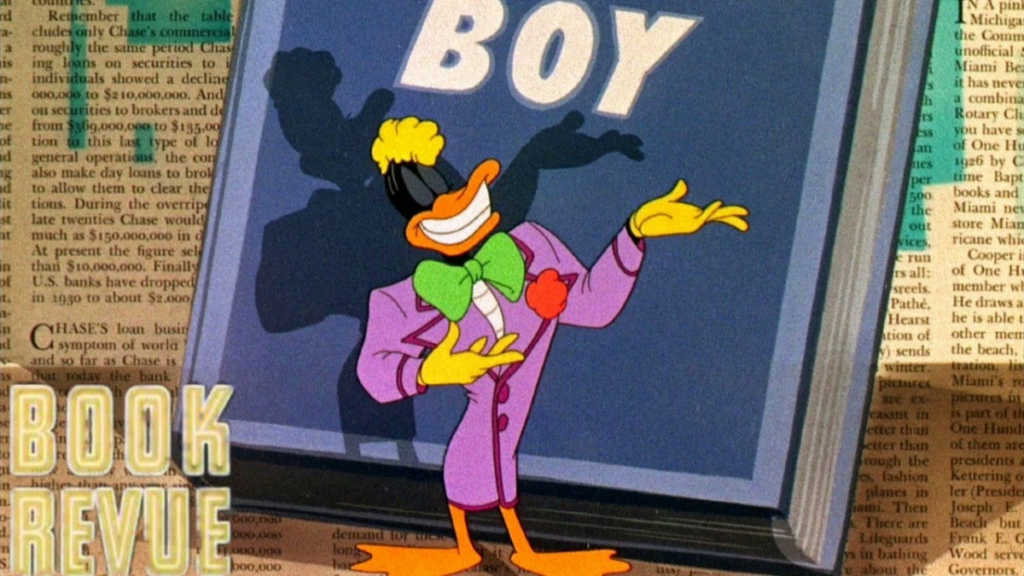

Although we may associate animation with children’s entertainment, historically, the form was not viewed as such from the outset. In the early part of the 20th century, films were primarily screened at night when children were in bed, so animation catered to all age types, incorporating crude adult humor and social/political commentary. Look at the Looney Tunes theatrical cartoons, for example, which commonly utilized these tactics to humorously poke fun at pop culture and world events. A great example from this series is the 1946 Bob Clampett cartoon Book Revue, in which a pile of books sitting in what is presumably a home library come to life at night when no one is awake. The cartoon playfully incorporates a slew of 1940s cultural and literary references (of which most now are not familiar to modern day audiences), while also having an entertaining fluid style of animation that is a lot of fun to watch for children and adults alike. This speaks leaps and bounds to the power of cell animation in particular, allowing this medium to represent ideas and scenarios that would be impossible to replicate in reality and in live-action film.

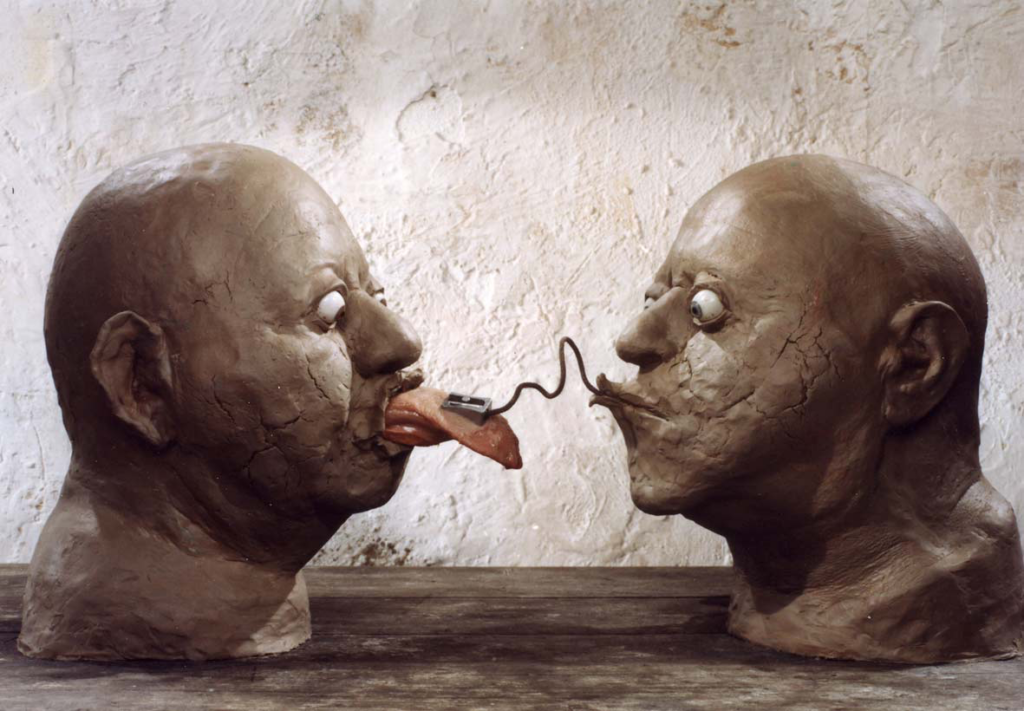

Additionally, animation can be a venue for artists and experimental filmmakers to play with the very conventions of film. An example given in Film Art is Dimensions of Dialogue by Czetch animator Jan Švankmajer, a film which uses everyday objects manipulated in a stop-motion style to convey three types of dialogue used in everyday life. Through three distinct segments, Švankmajer offers a pessimistic view of human communication, highlighting its inherent flaws and limitations through surreal object animation. By manipulating these objects in unnatural ways, animators can create dreamlike and often unsettling experiences that defy categorization.

Increasingly, animation is being accepted as a fully realized adult form, with shows like South Park, Family Guy, and BoJack Horseman offering a diverse range of styles and themes, playing with references to pop culture and social commentary in the same way that the Looney Tunes cartoons did 75 years ago. Taking a look at BoJack Horseman, we can see that the show has a lot to say about mental health, addiction, sexual harassment, and celebrity culture, among a lot of other themes, told through the lens of satirical comedy. BoJack, and shows like it, provide an outlet for this commentary in ways that live-action scenarios cannot because of the inherent flexibility of animation as a medium. Thankfully, they are paving the way for animation to be accepted as equally important/valid forms of film that are for adults and children alike.