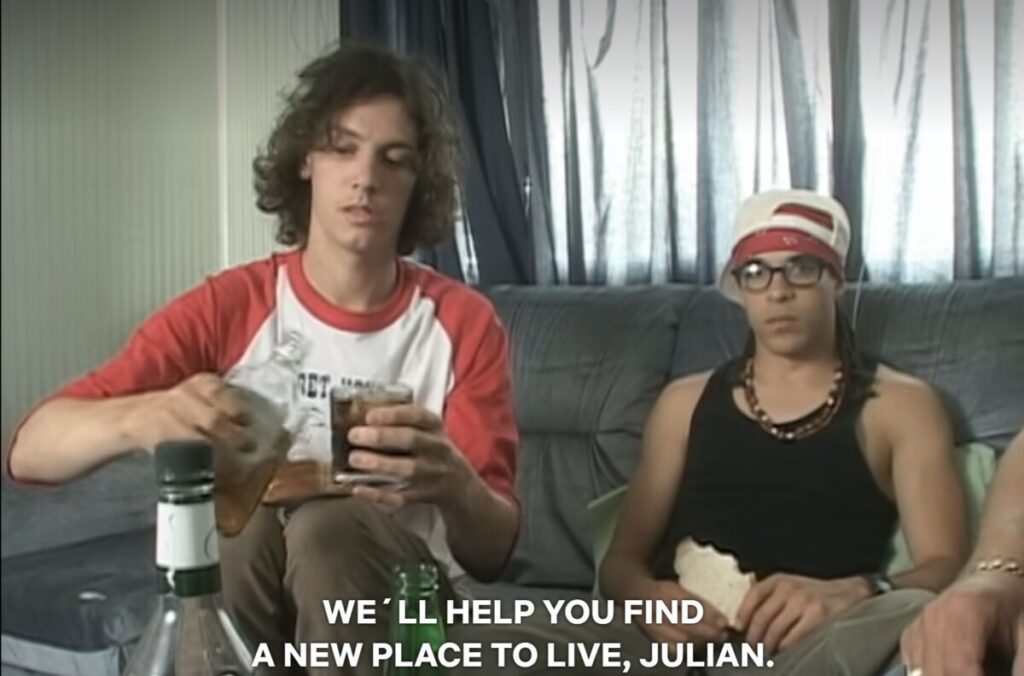

I might be the only person I know who can’t really feel immersed in TV shows. I often feel the corporate release schedule and network expectations result in a watered-down and exaggerated story. However, this feeling makes me uniquely interested in programs that abandon the traditional narrative in favor of complex moral discussions. Perhaps the best example of this type of show is Trailer Park Boys (2001-2018). After making an initial full feature called One Last Shot, the Director and Cinematographer of the mockumentary (Mike Clattenburg) won the Atlantic Film Festival’s award for cinematography, leading to angel investor Mike Volpe joining the project and financing network pitches for a full television series. What originally started as a local cable short produced by two of the main actors quickly turned into a Showcase-exclusive full season that aired in April, 2001 across Canada. The show stands out to me for its murky and conflicted message about crime and recidivism, but also for its dedication to the mockumentary genre. The best example of this dedication to the genre is visually shown through the character Julian. In the very first few scenes of the first episode, Julian is released from prison and returns home only to find out a rival criminal has taken over his trailer. His friends pour him a drink in response and for the subsequent 12 seasons, Julian carries around this glass from the park to prison and back and forth, taking a sip whenever times get tough. In the next 11 seasons and 17 years, this exact glass would be depicted in 4 different standard aspect ratios, and resolutions anywhere from 240p to 4K. This running gag transcends logic and temporal storytelling to remind you that what you’re seeing is a caricature of a social archetype.

(S1E1)

(S12E10)

Similarly, the cinematography of the show is constantly reminding you that this is a satirical mockumentary. Clattenburg continuously employs impractical and unnatural looking camera angles to drive this point home. In one episode, the main characters get into a very poorly “documented” shootout and the camera crew fails to notice what is happening, leading to a sound engineer getting “shot” in the leg. The director and writers make sure that the normal people in Nova Scotia, for example the local ER nurses and TV crew, are the butt of the joke which draws attention to how our characters end up in these compromised situations.

The main plot of the show has to do with our main characters, Ricky, Bubbles and Julian, attempting to buyout their home trailer park through a never ending series of flawed illegal schemes and businesses. In the process, an alcoholic retired police officer, also from the park, is doing everything in his power to keep the trio behind bars. The show does a thorough job of explaining how normal people end up living a lifetime of repetitive petty crime, due to the need for perceived status and satisfying personal vendettas. At the same time, whenever the consequences of these grudges are realized, the show and its characters react much less realistically and stylized in the direction of mockumentary. The boys are never sent to Jail for longer than a year or two, despite most of their crimes being international or violent in nature. Because the show choses to poke fun at systemic mental health failures and the overall Canadian justice system whenever the stakes are highest, the shows social commentary is surprisingly poignant. In many ways the dozens of court cases that easily get explained down by our main characters raise a valid concern about recidivism and the governances where it is common. The show continuously points towards the government and law enforcement as the source of motivation for the majority of their crimes. The characters commit many of these, like bootlegging Russian alcohol to get rid of the ex-military gate attendant or running an insurance fraud scheme on their own property, purely to rid themselves of government-imposed living restrictions and looming bankruptcy/eminent domain.

In the process of broadening the scope of its themes, the show gained immense popularity both in Canada and the US, as it grew to be the #2 most watched television program in Canada and was added to US Netflix in 2012. But this would also become a growing pain for the main showrunners. Ricky, Julian and Bubbles, real names Robb Wells, John Paul Tremblay and Mike Smith, had never renegotiated their contracts with Showcase as it came to its initial finale in 2011. This means for the entire duration of peak popularity on air, every actor from the main trio to extras were being paid the same union-set minimum wage. Many central characters left the show somewhat briefly during this period as filming took months, even years for most of the older seasons, and their actors were starting to find better paying, local roles at different Canadian production companies. To make matters worse, Wells Tremblay and Smith were unable to convince any production companies to help them fund a reboot after their contract expired with Showcase. Feedback from executives mentioned how the show’s vile language and backhanded morale would not be a good strategic fit for most companies, as most Canadian production companies interested in crime-comedy-mockumentaries were looking for a more black and white, light-hearted take on crime. In response, Wells, Tremblay and Smith purchased the rights to the show from Mike Clattenburg in 2013. They started their own independent production firm and began reviving the series. Actor John Dunsworth who played Lahey, the alcoholic cop-turned-trailer-park-supervisor, and also the series’ long-time casting director, died in 2017. With his death, the show was finally ended, but the original cast’s production company “Swearnet” continues to attempt launching new original series. As it turns out, studios and production companies may refuse to work on successful projects even if the monetary incentive is there. We don’t think of censorship as playing a large role in media today, but the truth is, technology only provides exceedingly subliminal barriers to subtly suppress ideas. In the past Swearnet would have simply retreated back to local TV and angel investors, but in the modern age, production & distribution costs are much higher, and small brands face much harsher PR exposure.

https://thegauntlet.ca/2014/09/04/trailer-park-boys-fight-corporate-censorship/