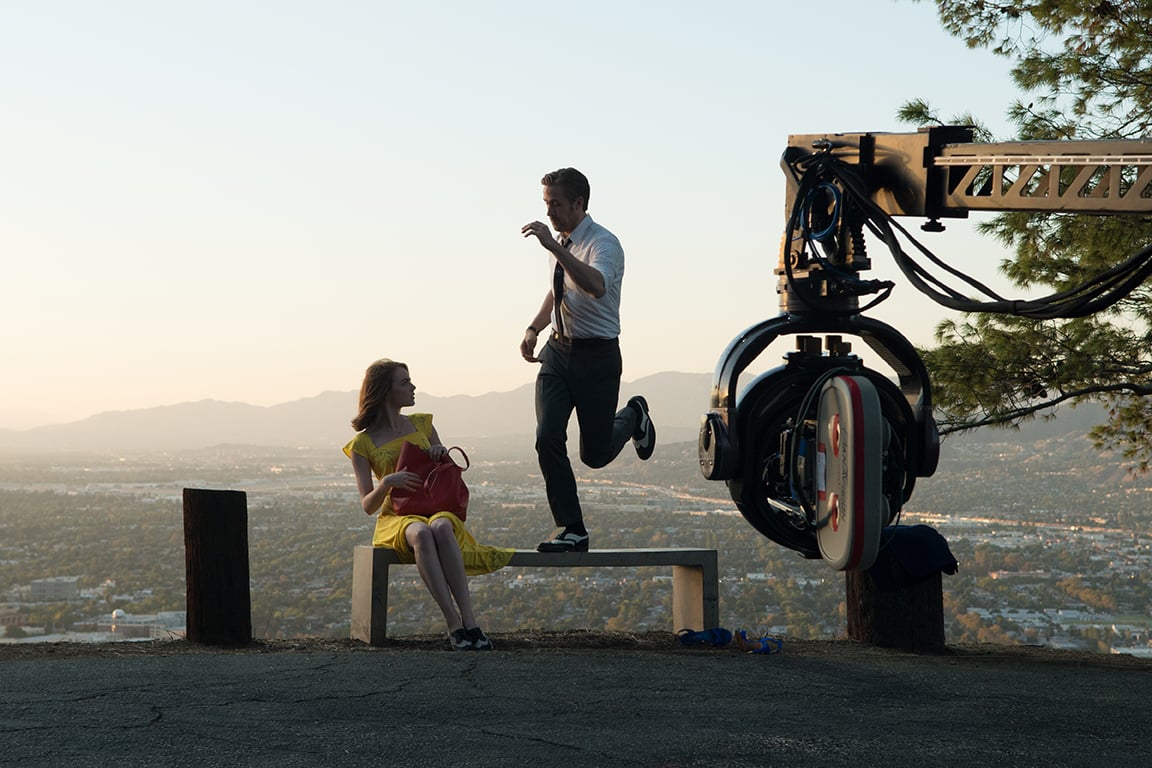

If mise-en-scéne refers to the objects placed in front of a camera, cinematography refers to how the camera captures said objects. This relates to the actual filming as well as post-production editing decisions. The factors involved in cinematography include on-screen light registration (affected by contrast and exposure), speed of motion, perspective/depth, framing, and shot movement. Various tools are utilized to produce these effects, mainly the camera and its various parts, including the lens and the physical film. There are also multiple people involved in the cinematographic process, including the director and/or cinematographers, those who set up and operate the camera, and editors who piece shots together, deciding which takes and what tonal qualities to use.

One prominent theme in this week’s chapter is how specific filming techniques can correlate with particular genres, primarily when they are known to elicit specific emotions. The feeling, for example, can be crucial for adding intensity to a film and keeping audiences engaged. Many cinematographic tools can be used to cultivate anticipation, including strategic framing that leaves items of interest just out of sight, slow camera movements that build tension, and specific camera angles that emphasize parts of the scene while hiding others. An overarching idea that encompasses all of these techniques is the concept of playing up the importance of what is off-screen. Just as with mise-en-scéne, a director/cinematographer has complete power over not just selecting what’s displayed in the frame but also what is omitted, which oftentimes is just as, if not more, important.

When analyzing cinematography, it is key to look for a director’s specific intent and not make assumptions based on a specific form. Though some cinematographic elements have been historically correlated with a specific genre or emotional use, one should not automatically assume that utilizing a technique is meant to blatantly categorize a film or emotion in one way or another. Instead, it is critical to use narrative clues to derive the cinematographic purpose. For example, Film Art provides a discussion on the use of mobile frames, or camera movement, for drastically different effects. In Grand Illusion, a World War I film, camera movement independent of the actors is employed to provide the audience with information the characters do not have about the war and build tension, as well as link characters with details of the environment for thematic purposes. Wavelength, on the other hand, uses camera mobility less for narrative storytelling and more to comment on the form of camera movements themselves.

All in all, the operation of the camera and the formatting of shots are just as crucial to portraying plot elements, themes, and messages in a film as the moments the camera is capturing. The physical form in which a story is portrayed should always be interpreted as an intentional decision, the meaning behind which will provide key insight into a film’s purpose.