When considering manuscripts from the middle ages, as much can be inferred from the materials and pictures as from the text itself, which is a blessing as most manuscripts are difficult to read for modern readers. Everything from the colors used to what the paper is made of has something to say about the manuscript. Take the English bestiary categorized as Royal 12 C. xix for example. Made in the first decade of the 1200s, this bestiary is one of the earliest surviving manuscripts to contain vivid paintings of animals and beasts (bl.uk). Although rebound in 1757 when it was gifted to the British Library by George II, the materials have a lot to say about this bestiary.

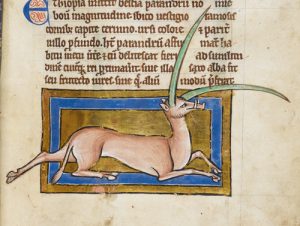

In the middle ages, the most popular colors of ink were red, blue, and of course black. Green and gold were a rare, and expensive, sight. As it is, this painting of a yale, or horned beast, has both rare colors. From the large amount of gold used in this image, as well as the green, we can infer that this manuscript spared no expense on coloring. Take also the fact that almost all the images have green and/or gold, including those pictures of normal animals, and we can further infer that this was made either for or by someone really wealthy, who demanded excellence in all manuscripts. Considering the fact it was later owned by George II, it is no surprise this manuscript is so rich in color.

In the middle ages, the most popular colors of ink were red, blue, and of course black. Green and gold were a rare, and expensive, sight. As it is, this painting of a yale, or horned beast, has both rare colors. From the large amount of gold used in this image, as well as the green, we can infer that this manuscript spared no expense on coloring. Take also the fact that almost all the images have green and/or gold, including those pictures of normal animals, and we can further infer that this was made either for or by someone really wealthy, who demanded excellence in all manuscripts. Considering the fact it was later owned by George II, it is no surprise this manuscript is so rich in color.

The fact that this manuscript is written in Latin also points to it belonging to someone wealthy. Latin was the language of the educated in the middle ages, so not everyone could read or write it. The individual who owned this was either educated enough to read Latin him or herself or had someone in his or her household he or she could pay to read it to him or her.

This manuscript is made of parchment, which is paper made of sheepskin. Parchment/sheepskin was one of the more popular paper materials of the time, the other being vellum, paper made of calfskin. This material was probably used as it was proven to last, unlike forms of paper that were not made from animal skin. In England in the middle ages, parchment and vellum far exceeded papyrus in paper usage, although papyrus has also been proven to last.

The manuscript measures 220 mm by 160 mm, or about 8 inches by 6 inches. The size of the manuscript shows this wasn’t a type the owner would carry around with him. Considering this isn’t a prayer or psalm manuscript, this is no surprise. The manuscript was probably left in the home and put on display or read occasionally when the feeling arose. It may have been read aloud at special events, but was not a manuscript for everyday or hourly use.

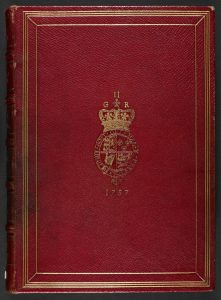

As mentioned, this manuscript was rebound by the British library in 1757. This indicates either the manuscript was falling apart, or they just rebound it because it would be easier to handle with a more modern binding. The manuscript has probably been opened a lot since it was rebound, accounting for the wear and tear on the spine and the slightly faded symbol on the cover. The symbol on the cover also points to its previous owner George II due to the initials at the top of the crest.

As mentioned, this manuscript was rebound by the British library in 1757. This indicates either the manuscript was falling apart, or they just rebound it because it would be easier to handle with a more modern binding. The manuscript has probably been opened a lot since it was rebound, accounting for the wear and tear on the spine and the slightly faded symbol on the cover. The symbol on the cover also points to its previous owner George II due to the initials at the top of the crest.

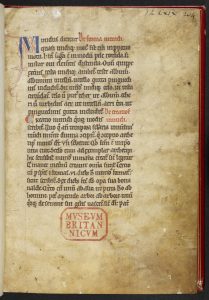

Along with the rich colors and Latin language, this text also indicates richness with its beautifully and carefully written script. We can see that the manuscript was written carefully  to look good via the pencil measurement lines that still remain to outline the space where the text would be written. The illuminated letters also point to a script meant to be displayed and bragged about.

to look good via the pencil measurement lines that still remain to outline the space where the text would be written. The illuminated letters also point to a script meant to be displayed and bragged about.

For those who don’t know, red text tended to indicate an important passage in the text of medieval manuscripts. Here we can see a couple places where the text was emphasized as important. Although modern readers who don’t know Latin would have difficulty understanding why said text was important, we can still infer it was significant due to the coloring.

In conclusion, this manuscript was clearly made for or by a very wealthy person, and the images point to no expenses spared in the making of this beautifully colored manuscript. Large but not too large, this text would’ve been put on display or read to crowds and definitely bragged about by the owner. In the end, this manuscript survived long enough to be appreciated by modern readers and readers in many ages to come. All this can be realized without even reading the text.