“All saints day” by Miroslav Petrasko (hdrshooter.com) is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Tradition, Experience, and Ritual:

An Embodied Approach to the Question of Suffering

“Why do bad things happen to good people?”

“How can I believe in a God when the world is so full of violence, destruction, and death?”

“That is the one thing keeping me from being religious. The question of evil. If God is all-powerful and all-loving, then why is there evil?”

The question of suffering is pervasive and eternal. When we witness horrendous pain, its is natural to ask “why” and to seek answers for how such evil permeates throughout existence if we claim traditions that portray God as loving and powerful. In the Christian tradition, we have historically made the following three claims:

-

- God exists.

- God is powerful and loving.

- There is suffering

Because the third claim is clearly evident in our experiences, theologians and philosophers have created “defenses” of God to explain the existence of a powerful and loving God despite the profound suffering of humanity.

The Free Will Defense has emerged as the primary theodicy in American mainstream Christian theology. It draws on the story of “The Fall” in the second creation narrative in Genesis and relies on the concept of original sin, as introduced by the theologian St. Augustine of Hippo in the 4th century. This theodicy asserts that humans were created perfect and good, and part of this goodness was autonomy, the freedom of the will.1 Humans then misused their will in disobeying God’s law in eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, which led to the entrance of suffering into the world.2 The permission of evil in the world implies that freedom was “worth the cost” of human suffering and serves as a good with a certain purpose, which humanity is unable to understand.3 This theodicy transfers the blame for suffering from God to humanity, emphasizing humanity’s role and ultimate guilt in evil’s presence in the world.

Another branch of this theological strain is Soul-Making Theodicy, which uses the same narrative of original sin with the additional assertion that suffering is constructive in that it creates conditions for spiritual growth.4 It also emphasizes free will, but suggests that suffering entered the world as a mistake, and that the entire human experience is full of mistakes in which we learn lessons that form us into mature souls.5

Both of these theodicies claim human culpability and emphasize divine sovereignty that is more powerful than suffering.

Other theodicists have pushed back against this theological narrative for its inability to comfort sufferers. In reaction to this theodicy, Marilyn McCord Adams states,

“Would the fact that God permitted horrors because they were constitutive means to God’s end of global perfection, or that God tolerated them because God could obtain that global end anyway, make the participant’s life more tolerable, more worth living for [them]?”6

Unsatisfied with the philosophical exercise of acquitting God for tragedy, feminist and process theologians have sought to offer new models of God’s sovereignty that illuminate God’s compassionate nature. Wendy Farley proposes a Tragic Vision, one in which finitude, freedom, and suffering are consequences of the structure of creation.7 She lifts up God’s compassion for humanity and desire for love as resistance to this structure. Farley names that theodicies themselves are forms of resistance, as they seek to question God’s responsibility within the reality of our suffering.8

Other theologians focus on incarnational theology and the role of Jesus’s crucifixion in the relationship between the divine and evil. Jürgen Moltmann attends to the Crucified God and Christ’s experience of abandonment that presents Christ on the cross as the center of salvation for those who suffer.9 Serene Jones lifts up the experiences of trauma survivors and their experience of the “Mirrored Cross” to illustrate how our suffering is mirrored to us through Christ’s suffering on the cross in solidarity.10

These theodical approaches have sought to resituate the experience of sufferers at the forefront of the discussion of God and evil, and in doing so, they have sought to create and disperse compassionate theologies that are held accountable to the lived realities of sufferers.

But do these theodicies adequately respond to sufferers seeking answers?

Most spiritual care practitioners and practical theologians say no.

These disciplines care have tended to shy away from theodicy due to claims of its lack of helpfulness to caring for persons. As Shelly Rambo states,

“The most familiar theological discourse about suffering is known as theodicy, the theoretical practice of reconciling claims about the goodness of God with the presence of evil in the world. While theodicies provide logic for thinking through religious claims about God’s nature and human suffering, they do not function effectively to address and respond to suffering. While theodicies might provide explanation, the degree to which explanations are helpful to the healing process is unclear.”11

These theodicies seek to provide answers for unspeakable pain, and such logical explanations for suffering cannot provide complete care for those currently suffering. When someone is experiencing profound pain, speculating on why they are experiencing suffering is not helpful as it does not comfort or relinquish pain; theodicy may try to “justify” their pain and cause more harm.

However, sufferers relentlessly seek to understand God’s role within their suffering, questioning their tradition and demanding answers. Tom Long states,

“For many Christians, the question of suffering, theirs and others, is not just a pastoral care matter; it is an intellectually troubling issue, one that they think about a great deal but do not have the resources to think through.”12

To mirror Tom Long’s sentiments, the question of suffering is one that individuals experience profoundly, yet many do not have resources within the Christian tradition to make sense of their lived realities with the theodicies they have inherited.

Tradition, then, acts as a constraint in that it limits the resources available to individuals. And the questioning of this tradition is an act of moral agency.

In questioning, individuals present their lives as sites of theological reflection. Feminist and womanist theologians and ethicists have sought to reposition the lives of sufferers at the forefront of theological analysis, and they have specifically sought to identify how different identities, backgrounds, and life experiences inform and form our theological reflection. Katie Cannon and Kelly Brown Douglas have lifted up the notion of “epistemological privilege,” the “taken-for-granted wisdom” that individuals gain as part of their life experience.13

Individuals use this wisdom to discern what theologies fit with their lived experience and to rework their commitments. Margaret Farley uses the language of “giving one’s word” in describing commitment, for there is a sense of placing a part of myself into another’s keeping.14 There is a relationship between the one committing and the one being committed to, and it is held together with a trust that both parties will honor this relationship. As one experiences suffering, however, they begin to question the role of these commitments and the character of the God in whom they placed their trust.

This questioning, this act of agency on the part of the sufferer, honors their experience, but can leave them unsure how to move forward.

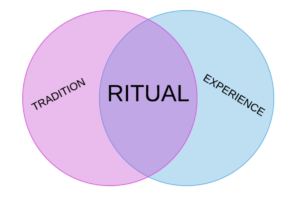

In this space of uncertainty, rituals can blur the space between the individual and their tradition. These liminal places, these physical spaces, can create room to embody theologies and work out the complexities of our faith.

Rituals transcend boundaries: the material and the immaterial, the individual and the communal, and the past, the present, and the future.

I am interested in how rituals can allow the individual to both work within and against their tradition as forms of moral agency amidst constraint. Tradition, thus, acts both as the constraint and the mode of agency simultaneously, but through different avenues. When activated intentionally, tradition can empower communities to creatively create spaces for reflection.

To illumine this intersection, I chose to attend and analyze a specific ritual: the Homeless Requiem Eucharist at the Cathedral of St. Philip on All Saints’ Day.

Requiem Eucharist

Each All Saints Day, the Cathedral of St. Philip hosts a requiem service to honor those experiencing homelessness in the city of Atlanta. This tradition has continued for the past 31 years, and as part of this night, there is a large communal meal, where those in the community and those experiencing homelessness gather around a table, and a Eucharist service where all gather around the Communion Table. Within the past decade, as part of their service, St. Philip’s has invited the Voices of Hope Choir from Lee Arrendale Women’s State prison to perform and worship as part of their ritual practice. Together, these communities unite in solidarity and mourning in remembrance and celebration of the dead.

This service is a significant case study because of the intersections of communities: the congregation of the Cathedral of St. Philip, Lee Arrendale State Prison inmates and security personnel, non-profit agencies targeting poverty and homelessness, and individuals experiencing homelessness, all of which are honoring the Christian holiday of All Saints Day. In these communities, both suffering and tragedy are present and united with the remembrance of death – that all who live will die, and we the living are called to honor those who have died. In the participation of this ritual, all look to God in their suffering.

In analyzing this service, I will be situating the caregiver as the moral agent. Though the attendees are themselves moral agents in that they are joining this community in remembrance, it is the priests of the Cathedral, the spiritual leaders and caregivers that are actors by creating the space for ritual. These caregivers will be lifted up and evaluated as moral agents to determine how their actions of ritual allow for the merging of tradition and experience.

Lens of Trauma

To hold caregivers accountable to the attendees’ experiences, there will be special attention to how the theologies conveyed in the services are responsive to trauma.

Trauma-sensitive theologies are sensitive to the ways that “death haunts life.”15

Trauma illumines what Shelly Rambo refers to as “The Middle,” the place where death and life are no longer bounded, the space situated between a painful past and a hopeful future, where there is survival.16 Theologies that hold space for this middle honor the realities of death in life, but they do not eclipse over these painful realities. They are critical of frameworks “in which the new replaces the old, and in which the good inevitably wins over evil.”17

The middle space of trauma is where sufferers speak out and question the God of their traditions.

“The traumatic event challenges an ordinary person to become a theologian, a philosopher, and a jurist. The survivor is called upon to articulate the values and beliefs that she once held and that the trauma destroyed. She stands mute before the emptiness of evil, feeling the insufficiency of any known system of explanation. Survivors of atrocity of every age and every culture come to a point in their testimony where all questions are reduced to one, spoken more in bewilderment than in outrage: Why? The answer is beyond human understanding.”18

In this remembrance of All Saints’ Day, there will be special attention to how the embedded theologies within the service are sensitive to trauma because of the tragedy present within the communities gathered.

Hymnody

The service included seven hymns, most of which were very well-known, so much so that those who casually attended church would be familiar with them. They also reflected ecumenical diversity, many coming from the Episcopal tradition, but others emerging from the Black Church tradition. In drawing from familiar resources, the service helped attendees feel connected to the worship space. While singing familiar tunes, the Cathedral was filled with liturgical solidarity.

Most of the hymns emphasized praise of God’s might and glory; “Love Divine” reflects on the hope that Christ will return and bring salvation, while “Come, Thou Fount” and “Lift Every Voice” focus on the individual’s praise of God’s grace in their life. These joyous valences of the hymns were also mirrored in the prayers and readings. There were countless “Hallelujah’s” and calls to rejoice in God and be joyful in triumph and victory for Their people. Only the hymn, “Precious Lord, Take My Hand” reflected a more emotional, meditative sound. This somber tune attended to weariness and fatigue through suffering. The composer repeats the refrain, “Take my hand, precious Lord, Lead me on,” emphasizing our pain and desire to be witnessed and held. There is an attention to weakness and darkness as part of life, and God’s calming presence amidst this pain.

I was greatly surprised by the positive, hopeful energy conveyed and produced by the hymnody and Scripture readings. Although I expected the liturgy to create a space for emotional catharsis, a different model of moral agency emerged: hope as resistance. They conveyed a devotion to a loving, powerful God who overcomes suffering.

Drawing on Wendy Farley’s phenomenology of tragic vision and divine compassion, God resists our suffering reality through compassion and divine love;19 God responds to the cries of God’s people in times of distress, seeking to liberate us from this tragic structure. This hope, this resistance to suffering manifest in the conviction that God will liberate, operates as a form of moral agency.

Ellen Ott Marshall defines four characteristics of hope.20 First, hope anticipates a good, and second, this good occurs in the future.21 Third, this good is difficult to obtain, for it cannot be obtained easily, but fourth, it is attainable.22 The hope manifest in this service was a faith in God’s power to save Their creation from evil and suffering: a future good that is difficult to acquire, but will be actualized because of God’s commitments to humanity. This hope, this conviction in God’s desire and ability to save Their people, is an implicit theodical claim that operates as a mode of moral agency that preserves and conserves personhood amidst profound suffering.

Sermon

The Word was offered by Rev. Marquetta Thomas, a woman who was formerly incarcerated and formerly experienced homelessness. She reflected upon her time living on the streets and her time in Lee Arrendale State Prison, both of which caused her to feel as if her “back was against the wall.” She described her times of helplessness, the times in which she felt as if she could not go on, and her decision to trust God. She praised what the Son of God sets free, and his victory over pain and suffering. She emphasized freedom, and the hope to be cultivated amidst bondage.

She ignited a solidarity within the congregation. The Voices of Hope Choir jumped to their feet as soon as she finished preaching, which was quickly followed by the participants in worship who sat in the first row. Row by row, the attendees jumped to their feet, inspired by her vulnerability and her passion. Her word was motivating in itself, as her piety and conviction were enough to move anyone to stand in hope.

Her positionality also united these diverse communities: her ordained status, her criminal record, and her experiences of poverty. She stood as a spiritual authority, and she stood as someone who knew what it means to live amidst bondage and constraint. Her body united this community in a way that music could not – through wisdom of what it means to suffer and to hope. In preaching, she embodied a form of moral agency, both individual and communal, as she stood as a witness to both the plights of pain and the joy of liberation. She stood and offered God’s Word to a community of strangers in an act of vulnerability and courage, and this community held her in reverence and praise.

Eucharist

At the center of the service, all were welcomed to the Communion Table to participate in the sacrament. During the Offertory, the acolytes processed down the rows and lit the individual candles that each congregation member was given at the start of the service. The Cathedral was quickly filled with light, the light of those who had died and of those that remain, and the candles remained lit through the duration of the Great Thanksgiving.

In honor of All Saints Day, there was space to remember those who had died on the streets of Atlanta this past year. Immediately after the blessing of the elements, the names of the dead were read one by one, with the tolling of the bells occurring after each name.

Over fifty names were called.

After a name was called, a member of the congregation would approach the altar and present a cross that bore the name of one of the dead. Each individual honored to carry a cross would step forward and carefully and reverently place the cross at the foot of the altar, and in doing so, placed their saint in the presence of Christ. In placing these crosses, these memories of departed souls who experienced tragic suffering at the foot of Christ’s cross, there was an experience of solidarity in suffering.

It was incredibly moving to watch each participant care for their cross: some experiencing homelessness, some Candler students, some employees of service organizations, etc. Those of all ages, genders, races, economic backgrounds, physical abilities, and religious affiliations stepped forward and honored the cross of an individual who died, with whom they most likely shared both similarities and differences.

By setting apart this time of service specifically to those who had died on the streets of Atlanta, their lives were recognized and memorialized to both honor them and bring awareness to this tragedy. This act simultaneously honored the lives lost and resisted the structures that perpetuate suffering, and in doing so, created space for a community to preserve the personhood of the dead and the living.

Hope

In analyzing this Requiem Eucharist, I had hoped that a form of moral agency would emerge in which space was created where members of all different communities could join together in grief and solidarity. This was actualized in some ways. Hope as a resistive and sustaining practice emerged as the most powerful theme of the ritual. The imagery of strangers from all across Atlanta uniting in remembrance of those lives lost on the streets of Atlanta was incredibly powerful. There was an aura of resistance, a demand for these deceased individuals to be seen and celebrated. This demand was echoed in a certainty in God’s power to overcome suffering and to save those who suffer from their pain.

In reflecting on the role of hope in this service, I am cautious to define hope as resistance as a mode of moral agency due to my fear that it is a limited narrative. I recognize that hope is powerful and faith in a God who is all-powerful and liberative is comforting, but I fear that in offering praise and joy as the only responses to pain, sufferers within this space may not feel able to grieve, and thus, feel more constrained in their context. In only offering hope in the form of future-oriented liberation, these attendees, our fellow sufferers, were left without resources to make sense of the divine’s presence in their current state of pain. This left the individual in this helpless middle questioning if their God will provide, and if They can, why They have not yet. For those that struggle with concepts of God’s justice, this service constrained their ability to fully grieve for their loved ones and for their own pain.

As caregivers, to exercise moral agency within a tradition is to provide space for sufferers to honor the tragedy in their life, whether it be through praise of a liberating God or lament with a suffering God. Ritual allows for this provision of space, and though it can also reinforce traditional norms, ritual allows the moral agent to embody their experience and lift it to God.

Want to know more about this author? Click here!

Footnotes

- Mark S.M. Scott, Pathways in Theodicy: An Introduction to the Problem of Evil (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2015), 70.

- Ibid., 70.

- Ibid., 75.

- Ibid., 112.

- Ibid., 103.

- Marilyn McCord Adams, “Horrendous Evils and the Goodness of God” in The Problem of Evil, eds. Marilyn McCord Adams and Robert M. Adams, eds., New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 214.

- Wendy Farley, Tragic Vision and Divine Compassion: A Contemporary Theodicy (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1990), 31-32.

- Ibid., 95.

- Jürgen Moltmann, The Crucified God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2015), 62.

- Serene Jones, Trauma and Grace: Theology in a Ruptured World, 2nd ed. (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2019), 77.

- Shelly Rambo, Spirit and Trauma: A Theology of Remaining (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2010), 5.

- Thomas G Long, What Shall We Say?: Evil, Suffering, and the Crisis of Faith (Grand Rapids, MN: Eerdman’s, 2013), 30.

- Kelly B. Douglas, “Twenty Years a Womanist,” In Deeper Shades of Purpose: Womanism in Religion and Society ed. Stacey M. Floyd-Thomas, (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2006), 148.

- Margaret Farley, Personal Commitments: Beginning, Keeping, Changing, Revised Edition, (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 2013), 52.

- Shelly Rambo, Spirit and Trauma, 3.

- Ibid., 130

- Ibid., 6

- Judith Herman, Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2015).

- Wendy Farley, Tragic Vision and Divine Compassion, 107.

- Ellen Ott Marshall, Though the Fig Tree Does Not Blossom: Toward a Responsible Theology of Christian Hope (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2006), 17.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.