Nadra and Ghazel first came to North America as refugees. Today, they are actively involved in their communities as mothers, teachers, learners, and leaders. I invite you to listen in with me and attend to the insights they share about life following resettlement and the responsive, expansive nature of moral agency under constraint.

Constraint: “It’s Like You’re on Your Own”

In 2009, Ghazel’s family began to receive threatening notices warning them that “half-Americans” were no longer safe in Iraq.[1] They were charged with this label because of her husband’s job on a U.S. military base—a job that also led to their expedited resettlement to the U.S. a year later through the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) program.[2] A mother of three, Ghazel speaks powerfully to the overlapping, cumulative effect of the constraints that characterized her life following the resettlement process:

I used to hear of lots of parties or workshops or something, but there’s no childcare for them. So how can I go, how can I share my opinion, my ideas? How can you listen to me and I listen to you?[3]

The absence of childcare, combined with the language barrier and the stress of daily life in an unfamiliar context, left Ghazel feeling isolated and overwhelmed during her first three years in Clarkston, Georgia.[4]

In contrast to Ghazel, Nadra experienced a protracted process of migration and resettlement starting at a young age.[5] After an outbreak of violence killed her mother when Nadra was six years-old, she and her siblings fled from Somalia to Kenya with relatives, where they lived until she was twelve. During that time period, her father was granted asylum in Canada. Resettlement eventually enabled the family to reunite near Toronto; Nadra lived there with her father and siblings until 2006, when she moved to Stone Mountain to marry her now-husband. Her experiences in Georgia were nonetheless strikingly similar to Ghazel’s. In spite of her English proficiency and her familiarity with Western culture, Nadra became isolated after her move, lacking both the social bridges (relationships with people outside of her ethnic community) and the social bonds (relationships within her community) that some scholars suggest act as essential conduits of integration.[6] She muses,

The living here is different…it’s like you’re on your own. It’s really difficult here, but we’re living. Life goes on. You can see that.[7]

With only one sibling living nearby—a dramatic change for a woman who grew up with a large extended family and tribal network in close proximity—Nadra explains, “I felt very lonely the first couple of years here, yeah, because it wasn’t the same. I couldn’t just go wherever I wanted to go to see family members, they were not home, they were working, everybody was running for their lives here. It was so different, so I had to adjust to that. It took me long, long years.”[8]

Drawing on stories shared by Ghazel, Nadra, and other women who first came to the U.S. as refugees, I would posit that constraint can be defined as a situation that limits an agent’s choices and opportunities against her wishes and thereby poses a threat to individual and collective flourishing. Whether one considers the pressure to find early employment created by U.S. resettlement policy and the premature termination of services, the prejudice refugees face in their new home communities, the histories of sexual violence and other traumas that innumerable refugee women must work to cope with once here, or the more limited access to education and vocational opportunities that women might have had in their countries of origins, it is clear that systemic and structural constraints do not just mar the resettlement experiences of women. Rather, constraints are embedded in the very fabric of the process.[9]

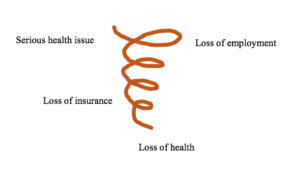

Further, I would posit that women’s resettlement experiences highlight the way constraints frequently occur in compounding and converging patterns. As one constraint bumps into another, they both deepen and expand. Susan Sered and Rushika Fernandopulle’s notion of the “death spiral” is clarifying on this front. Developed to illustrate the precarious state of healthcare in the U.S., the death spiral represents interlocking issues that each have the capacity to trigger a downward turn, trapping the individual in untenable situations and blocking key resources that might have otherwise been accessed to support coping. Distinguished by multiple entry points and very few exits, in the original death spiral an individual might lose his or her job, which in turn results in the loss of health insurance and heightened vulnerability to health crises. Alternately, he or she might experience a health crisis that then results in the loss of employment and, subsequently, of health insurance. Whatever the entry point, the result ultimately is loss of health and well-being.[10]

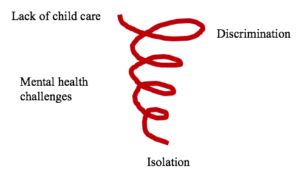

In the resettlement version of the spiral, an external constraint like the absence of opportunities to learn English can rapidly lead to an internal constraint like mental health challenges, fear, weariness, or despair. Any of these internal constraints might, in turn, make overcoming an external constraint all the more daunting. With each turn of the spiral, the individual is pushed further down, gradually moving closer and closer to the pit of the spiral that culminates in isolation in its most forceful and totalizing form.

Moral Agency: “We Don’t Want to Stay at Home”

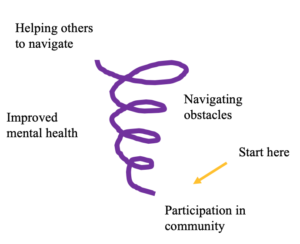

Attending carefully to the stories of women in the Clarkston community, however, reveals that this spiral can be multidirectional. Agentive action can, at times, reverse the spiral. When they holistically and creatively participate in the education system in Clarkston and the surrounding area as mothers, learners, teachers, and community leaders, women like Ghazel and Nadra contribute to this work of reversal, causing the spiral to spin upwards instead.

With the help of Nadra and Ghazel, I have come to see moral agency as a form of contextualized responsiveness that moves to affirm personhood and honor connection in the face of constraints.

By engaging in the improvisational process of making do with the resources they are able to access, they reshape their post-resettlement lives in ways that not only benefit themselves, but also their families and communities.

Affirming Personhood

I first met Ghazel at a 2014 community dialogue in Clarkston. She actively participated in the event, creatively imagining a community-based solution to a challenge facing the public education system: an insufficient number of multi-lingual, culturally-sensitive instructors in both schools and early learning centers. Ghazel recalls sharing the following during the dialogue series, which was convened by CDF (a Clarkston-based community development nonprofit) with funding from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation:

We tell them that we need a job for us, we don’t want to stay at home and, you know, just have a foolish time or something. We want to work, ok…so we think that the best thing that we can do is to be a teacher in a childcare center with each other…Even if we don’t have the studies certificate or something, we have the experience because we are mommies.[11]

Ghazel’s proposed solution doubles as a compelling affirmation of personhood, an insistence on her own giftedness in the face of a resettlement process that primarily perceives individuals through the lens of need. She speaks to this dynamic directly when telling me about how motivated she is to participate in the workforce as an Iraqi woman. Noting that women do not typically work outside of the home in Iraq, she quickly learned that this is not the case in the U.S. “You know,” she muses, “we’re here in America, so I do believe that all people, all women have something that like…they want to do something good. They want to help. They want to have, you know, their place in the community. They really want to do something…It’s not all about the husband, husband, husband. This idea needs to be changed!”[12]

Ghazel’s participation in the community dialogues alongside women from other countries and cultures led to significant change in the Clarkston community. In response to dialogue participants’ requests, CDF used the Kellogg Foundation grant in partnership with Georgia Piedmont Technical College to offer training for the Child Development Associate (CDA)—the credential required to work in early learning centers in Georgia—in both Arabic and Somali. Ghazel was one of the first women to commit to the requisite 120 hours of coursework and practicum, and she encouraged other Iraqi mothers in her community to participate as well.

Nadra participated in the CDA program a year after Ghazel. Initially connected to CDF through her sister, Nadra found that the class provided relief from the relentless pace at home as a mother of four at the time. She explains, “Going to CDA class is really just ‘me’ time, that time when I go there. [It’s] some time to clear my head, focus, enjoy those hours, right.”[13] As a self-affirmation of personhood, Nadra’s decision to claim time to invest in herself and develop new skills should also be seen as a subtle, yet powerful, act of moral agency.

Honoring Connection

In contrast to the loneliness she initially experienced in Georgia, Nadra found that the CDA class provided an opportunity to connect with women who had faced experiences similar to her own, yet who came from different parts of the world. A few weeks into the class, she started inviting classmates over to her home in Stone Mountain— the first time she had the opportunity to engage in hospitality in the “Somali way” since moving here. Describing her conviction about the importance of this practice, Nadra says:

It’s a fun thing that I have, that I carried from my country, from back home. It’s a thing that I’m doing now, and it’s such a good thing—it’s helping. I see that it’s helping a lot of people, so I’m going to keep on doing it because I need it worse than them! When I go out, when they [invite me to] their houses and I leave the kids with my husband and I go out, I come back happy. I come back fresh.[14]

Having her classmates over and returning their visits sustains Nadra and, in all likelihood, helps to sustain her peers as well. She returns from this time with other women “fresh” and resilient, ready to face the day-to-day challenges of being a hijabi Muslim woman in frequently homogenous, Judeo-Christian spaces and of raising her children in a context that often confronts her values.

Nadra also consistently seeks to interweave support for her own family with support for other, more recently-arrived refugee families. In 2017, when I first interviewed Nadra and Ghazel as part of CDF’s community-based research initiative, this commitment was embodied in her concrete, daily actions at the READY School—a multi-lingual early learning program designed by CDF in conversation with Clarkston families—where she was not only teaching, but also offering culturally-appropriate advice to other mothers. Explaining her proactive approach, she stresses, “We don’t have a country that we can be successful in, where our language is spoken, where we understand each other, and where professors speak Somali; we don’t have that here. So we have to strive, struggle to get the best out of whatever America has to offer our community.”[15] In choosing to extend her network of obligation beyond her nuclear family, Nadra honors the reality of interdependence and connection and makes the struggle a little less arduous for others. Of her role as cultural liaison between her U.S.-born co-teacher and the parents of her students, she explains:

This is how I see it: it’s like, you know, when you’re lending a hand to somebody who is sitting on the floor who needs to get up. And you give them your hand and help them; you pull them up and you help them to get up. That’s what [the READY School] is doing…I want to be around for a long time, it’s good for those newcomers, especially for them! Because when they come to this country, they don’t speak the language, they feel lost. So, when they come to school, we talk with them, we laugh with them, we joke with them, and we tell them what letter we did today…And then they start laughing! And they feel so comfortable.[16]

Ghazel, like Nadra, was able to use her CDA certificate as a springboard into meaningful employment. Ghazel proudly tells me of her work as an assistant teacher at the Global Montessori School soon after starting her new position in the spring of 2017. She shares, “I go and work, and not only that—I help the people who speak Arabic. When they bring their children, they feel safe because I’m there. We share the same values. Even if we’re not from the same country, our values are the same.”[17] Given how different the American public education system is from that of other countries, the value of Ghazel’s comforting, familiar presence within that system for newly arrived refugee parents cannot be overstated.

Contextualized Responsiveness

In both Ghazel and Nadra’s stories, we see a commitment to responding to the particulars of the situations in which they find themselves with care and creativity. At the time of our initial interviews, this responsiveness took the form of their work as informal mentors to the families of children in their classrooms. When I reconnect with them two years later, in the fall of 2019, I find that they are continuing to act as moral agents, albeit in new, contextualized ways.

Neither are working at present, in large part because both have given birth in the past year. Ghazel stays busy advocating for her children in the public school system through frequent meetings with their teachers and principal. While she is currently in more of an interiorly-focused season of life than she was during the period of our extended conversations in 2017, she continues to dream about and plan for future opportunities. She is considering pursuing training as a medical assistant or interpreter once her month-old son is a little older, as she believes this might enable her to have more of a direct impact in the community. Ghazel once told me, “I want my children to be proud of me, in the future, yes. But the most important thing is I want to be proud of myself.”[18] This high standard will no doubt continue to fuel her creative community participation far into the future.

Nadra, whose fifth child is now almost one, dreams of returning to school. In the past, she had shared hopes of becoming an elementary school teacher, of starting a daycare in her home, or of one day creating a larger version of the READY School in the Clarkston community so that children of all ages could benefit. As such, her aspiration to pursue higher education does not come as a surprise. In actively choosing to include the Somali community as well as other “newcomers” in her umbrella of concern—all the while maintaining time for herself and her family—I see Nadra adroitly practicing moral agency in her daily life.

Seedlings of Moral Agency

In their journey to make space for themselves and their families in their new home communities, Nadra and Ghazel reveal the inherent promise and pitfalls of resettlement as it is currently structured. They highlight the need for a holistic model of integration and lend narrative weight to Morgan Poteet and Shiva Nourpanah’s claim that, “in the current context of increasing restrictions on refugee settlement and integration, addressing issues of exclusion and marginalization for refugees may be at least as important as trying to nurture social capital.”[19] Stories like these are important not only because they can help us better understand what it is like to live in the U.S. following the experience of refugee resettlement; they also speak to the role we have to play as members of receiving communities. In listening to stories like Nadra’s and Ghazel’s, we are drawn into the unfolding process of moral agency. As we begin to develop a richer sense of the context of constraint, the possibility of a contextualized response emerges.

Ghazel and Nadra’s stories also reveal a hopeful truth about the nature of moral agency: just as constraints converge and compound, so too, in a way, does moral agency.

Nadra and Ghazel show us that acts of moral agency create the conditions necessary for the cultivation of new acts of moral agency.

The initial act provides temporary shelter from the heat of constraints, allowing seedling acts of agency to sprout. These “seedlings” of moral agency might take root within the original agent, within a witness of the agentive act, or within someone who was impacted by that act. As Nadra and Ghazel take steps to participate in the community, they simultaneously remove some of the barriers previously facing them and make those barriers a little easier to navigate for others. While I had previously thought about this in the metaphorical terms of the resettlement spiral, I would posit that this can be brought into generative conversation with the metaphor of the seedling as well. As one act of moral agency after another provides a canopy of protection to support new acts, might an ecosystem of moral agency develop? An ecosystem so healthy and verdant that the “weed” of the resettlement spiral is starved of the “nutrients” (i.e., constraints) that it needs to grow? As agents like Nadra and Ghazel creatively participate in their communities, it seems possible that they might eventually whittle away against at least some of the constraints of the resettlement landscape. While these are only musings at present, what I am sure of is this: as Ghazel and Nadra continue to act in ways that honor their interdependence and affirm their personhood, they wind their way out of isolation and step forward in the direction of flourishing. And, in so doing, they gently pull others along with them.

Acknowledgements

Initial research for this essay (the 2017 conversations with Nadra and Ghazel) was conducted through CDF: A Collective Action Initiative, with funding from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. The “Portraiture Project: Conversations in the Clarkston Community” was launched with the goal of learning more about community members’ experiences with CDF’s programs and in the Clarkston community overall. I want to thank Roberta Malavenda, CDF’s executive director, who initially conceived of this community research initiative and who gave permission for data from this work to be revisited. Finally, I give thanks to Nadra and Ghazel, not only for allowing me to share their stories, but also for the hopeful and compelling witness they bear to the power of moral agency under constraint.

[1] Ghazel’s name has been changed for the protection of her privacy. She requested that the name “Ghazel” be used instead, as it is the name of a loved one and is common in Iraq.

[2] SIVs are reserved exclusively for individuals and families whose lives have been endangered as a result of their work with the U.S. military in Afghanistan and Iraq.

[3] Ghazel, Interview by Janelle Moore, Clarkston, GA on March 3, 2017.

[4] Clarkston, Georgia, located just 20 miles east of downtown Atlanta, has been a hub for refugee resettlement since the early 1990s, when multiple voluntary agencies identified the community as having the ideal combination of proximity to large employers, affordable housing, and access to public transportation.

[5] Nadra’s name has been changed for the protection of her privacy. She requested the name “Nadra” as her pseudonym, which means “the light that comes from the eyes” in Somali. Interview by Janelle Moore, Stone Mountain, GA on March 29, 2017.

[6] Michaela Hynie, Ashley Korn, and Dan Tao, “Social Context and Integration for Government Assisted Refugees in Ontario, Canada,” in After the Flight: The Dynamics of Refugee Settlement and Integration, ed. Morgan Poteet and Shiva Nourpanah (Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016), 183–223; see also A. Ager and A. Strang, “Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework,” Journal of Refugee Studies 21, no. 2 (April 18, 2008): 166–91, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fen016.

[7] Nadra, Interview by Janelle Moore, Stone Mountain, GA on Feb. 28, 2017.

[8] Nadra, March 15, 2017.

[9] Badiah Haffejee and Jean F. East, “African Women Refugee Resettlement: A Womanist Analysis,” Affilia 31, no. 2 (May 2016): 235, https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109915595840; Morgan Poteet and Shiva Nourpanah, “Introduction,” in After the Flight: The Dynamics of Refugee Settlement and Integration (Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016), xxii, xvi; Fethi Keles, “The Structural Negligence of US Refugee Resettlement Policy,” Anthropology News 49, no. 5 (May 2008): 6; Karin Wachter et al., “Unsettled Integration: Pre- and Post-Migration Factors in Congolese Refugee Women’s Resettlement Experiences in the United States,” International Social Work 59, no. 6 (November 2016): 883; Irina Isaakyan, “Integration Paradigms in Europe and North America,” in Routledge Handbook of Immigration and Refugee Studies, ed. Anna Triandafyllidou, Routledge International Handbook (Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge, 2016), 174; Jenny Phillimore and Lisa Goodson, “Making a Place in the Global City: The Relevance of Indicators of Integration,” Journal of Refugee Studies 21 (September 1, 2008): 5; Linda L. Halcón, Cheryl L. Robertson, and Karen A. Monsen, “Evaluating Health Realization for Coping Among Refugee Women,” Journal of Loss and Trauma 15, no. 5 (September 14, 2010): 409.

[10] Susan Starr Sered and Rushika J. Fernandopulle, Uninsured in America: Life and Death in the Land of Opportunity (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 2005), 6.[11] Ghazel, March 2, 2017.

[12] Ghazel, March 16, 2017.

[13] Nadra, March 15, 2017.

[14] Nadra, Feb. 28, 2017.

[15] Nadra, March 29, 2017.

[16] Nadra, March 22, 2017.

[17] Ghazel, May 24, 2017.

[18] Ghazel, May 24, 2017.

[19] Poteet and Nourpanah, “Introduction,” xxiv.