“Monuments: Our Immigrant Mothers,” by Yehimi Cambrón; used by permission of the artist; photo credit: Silas W. Allard

I cannot tell anymore when a door opens or closes,

I can only hear the frame saying, Walk through.Ada Limón, “Sharks in the Rivers”1

On Christmas Day, 2005, Aminta Cifuentes and her three children crossed the border between the United States and Mexico. Crossing this border was the goal of a long journey from their native Guatemala. In Guatemala, Ms. Cifuentes had survived years of terrible physical, sexual, and emotional abuse by her husband. Her efforts to end the abuse were unavailing. She appealed to the Guatemalan authorities, but the police refused to intervene; she relocated within Guatemala, but her husband found her. Convinced that there would be no safety for herself and her children in Guatemala, Ms. Cifuentes undertook the arduous trek to the United States to seek asylum.2

When Ms. Cifuentes entered in the United States as an asylum seeker in 2005, it was not clear whether an asylum claim based on domestic violence would be viable. A prior domestic violence case, Matter of R-A-, had been circulating through various levels of the immigration courts since 1999 and would not be fully resolved until 2009.3 In 2009, the government agreed to accept R.A.’s asylum claim but only on the facts of her specific experience of domestic violence in Guatemala.4 Resolved in this manner, however, the decision to grant asylum in Matter of R-A- was limited to the particular facts of that case; it did not guarantee that future cases would be treated the same. In legal parlance, the case was considered non-precedential and did not control the decisions of other judges.

Arriving into this uncertainty, Ms. Cifuentes’s own case would spend nearly ten years in the immigration courts. Ms. Cifuentes was initially denied asylum by the immigration court, but in 2014 the Board of Immigration Appeals issued a precedential decision in her case, known as Matter of A-R-C-G-, stating that “married women in Guatemala who are unable to leave a relationship” would qualify as a particular social group, thereby recognizing that domestic violence could be the basis for an asylum claim.5 Ms. Cifuentes’s own case returned to the immigration court where, in light of the Board’s decision, her asylum claim was granted, and she went from being an asylum seeker to an asylee. In the process, she had opened the door to many more asylum claims, which would quickly begin to build on the decision in Matter of A-R-C-G-.

Four years after Matter of A-R-C-G- changed the law of asylum by establishing a path for survivors of domestic violence, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions personally decided the case of another survivor of domestic violence, this time from El Salvador.6 Attorney General Sessions used this new case, Matter of A-B-, as an opportunity to overturn Matter of A-R-C-G- as, in his opinion, wrongly decided.7 In subsequent public remarks, Sessions referred to his decision in Matter of A-B- as part of his efforts to end abuse of the asylum process, and elsewhere he has described those making claims that push at the margins of existing law as “frauds.”8

So, is Ms. Cifuentes an asylee or a fraud? The answer depends on how you understand the definition of a refugee9 and the role of the asylum seeker in negotiating that definition.

Categories are important for law, and they are especially important for asylum law. The boundaries of legal categories are determined by definitions that describe what falls within and what falls outside the category. But, categories—even legal categories—are not static; the boundaries set by the definitions shift and move. The line of cases from Matter of R-A- to Matter of A-R-C-G- to Matter of A-B- makes this clear. The boundaries of the category of asylum shifted with each decision. This can be unsettling for judges, policymakers, academics, and the public, many of whom would like an easily discernible way of knowing who is an asylee. But, despite the common use of aquatic metaphors to describe people fleeing persecution—flows, waves, floods10—the category of asylum is not an empty vessel waiting to be filled by the right kind of person, with the right kind of experiences. When our public conversations about asylum avoid attention to the asylum seekers inhabiting and contesting the categories, we are left with—or perpetuate—the mistaken perception that there is a stable and, therefore, restrictive definition of asylum.

By attending, instead, to the moral agency of asylum seekers—the actions that asylum seekers take in pursuit of flourishing for themselves and others—we can begin to see how the category of asylum is negotiated by those who make a claim to it. Asylum seekers negotiate the category of asylum by navigating within its boundaries, but they also negotiate the category by contesting those boundaries.

Before examining the moral agency of asylum seekers, it is important to understand the context of and the constraints imposed on asylum seekers by how the category is defined and applied.

Defining Asylum

We live, today, in a world of nation-states, and one of the defining characteristics of the nation-state is its exclusive claim to territory. As U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Johnson Field wrote for a unanimous court in the infamous Chinese Exclusion case:

The power of exclusion of foreigners being an incident of sovereignty belonging to the government of the United States as a part of those sovereign powers delegated by the constitution, the right to its exercise at any time when, in the judgment of the government, the interests of the country require it, cannot be granted away or restrained on behalf of any one.11

This principle of exclusive territorial sovereignty means that the baseline—the first principle of the law of international migration—is the state’s largely unfettered power to exclude non-citizens from state territory.

The ability to exclude is not the same as a practice of exclusion. The vast majority of states, however, have created structures that begin with the principle of exclusion and permit entry only for categories of persons who qualify for admission.12 Like the 1971 Gene Wilder classic, Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, these restrictionist immigration regimes operate on a golden ticket system; in order to be admitted into a country, a migrant needs to possess an often rare ticket. Thus, between the principle of exclusive territorial sovereignty and restrictionist policies of admission, opportunities for international migration are highly constrained.

A golden ticket system obviously fails asylum seekers.13 Asylum seekers are fleeing harm, and they cannot afford to wait for a golden ticket. In recognition of this reality, a complementary legal framework emerged in the aftermath of World War II that acknowledges exceptions to the restrictionist regime for refugees and asylees. This complementary legal framework, however, contains its own constraints. Just as a migrant must have a qualifying ticket to be admitted generally, asylum seekers must meet the definition of a refugee for their asylum claim to be granted.

The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, as amended by the 1967 Protocol to the Convention,14 defines a refugee as any person who

owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.15

To meet the definition of a refugee and qualify for asylum, asylum seekers must have experienced a particular kind of harm (persecution) for particular reasons (on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group). Thus, every asylum seeker must attempt to conform the narrative of their experience to these definitional constraints.

Claiming Asylum

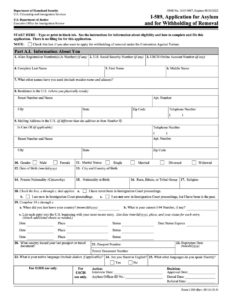

In the United States, this begins with the asylum seeker submitting an “I-589 Application for Asylum and for Withholding of Removal.” The following questions appear on page 5 of the I-589:

-

- Why are you applying for asylum or withholding of removal under section 241(b)(3) of the INA, or for withholding of removal under the Convention Against Torture? Check the appropriate box(es) [race, religion, nationality, political opinion, membership in a particular social group] below and then provide detailed answers to questions A and B below.

- Question A: Have you, your family, or close friends or colleagues ever experienced harm or mistreatment or threats in the past by anyone?

- Question B: Do you fear harm or mistreatment if you return to your home country?

In the language used by the government offices that make decisions on asylum—the United States Citizen and Immigration Service and the Executive Office of Immigration Review—the asylum seeker is an applicant. Construing asylum as an application process is misleading because it suggests that asylum is a benefit to be granted from the largesse of the government. But, asylum is not an application; rather, it is a moral and legal claim—a demand to be recognized—asserted by the asylum seeker.

The asylum seeker is making a legal claim to the status of a refugee and the protection required of states by international and domestic law. The asylum seeker is making a legal claim that the asylum seeker’s experience conforms to the definition of a refugee. Questions A and B on the I-589 form are an opportunity for the asylum seeker to tell a story in a way that will be recognized under the law. In this way, the asylum seeker’s claim must negotiate the boundaries of the refugee definition as they are established at the time the asylum seeker makes the claim. For example, when Ms. Cifuentes made her asylum claim, whether domestic violence fell within those boundaries was disputed. Following Matter of A-R-C-G-, it was much easier for survivors to claim that their experience clearly fell within the boundaries of the definition. When Attorney General Sessions overruled Matter of A-R-C-G-, however, it became much more difficult for survivors to negotiate the new, narrower boundaries of the definition.

While the asylum seeker must navigate the established boundaries of the definition, the asylum seeker’s claim is not contained by those boundaries. The claim is also a moral demand for recognition and protection that exceeds any simple categorization. Each asylum seeker’s story is unique and, therefore, each claim not only asserts that the asylum’s seeker’s story does conform to the the refugee definition but that the definition should accommodate the asylum seeker’s story. Thus, each new claim not only negotiates the existing boundaries of who counts as a refugee based on prior claims, each new claim renegotiates those boundaries.

Sometimes this moral demand results in a narrow renegotiation of the legal category, as in the non-precedential decision in Matter of R-A-, and sometimes this moral negotiation renegotiates the legal category in a much more profound way, as in the precedential decision in Matter of A-R-C-G-. In both cases, the legal and moral claim is a demand for recognition and response and, therefore, an opportunity to evolve16 the refugee definition and expand who counts as a refugee or an asylee.

Negotiating Asylum

When Attorney General Sessions used Matter of A-B- to overturn Matter of A-R-C-G-, thereby making it more difficult for survivors of domestic violence to succeed in their asylum claims, he sought to restrict the category of asylum by fixing the boundaries of the category. Like the wall along the U.S.-Mexico border, Sessions’s strategy was17 to construct a hard and fast boundary around the category of asylum and, thereby, foreclose the possibility of asylum seeker’s exercising their moral agency. For Sessions, the rule of law means clear, bright-line distinctions between refugees and frauds. That is not how the law of asylum works (or how the rule of law works, for that matter).

The moral agency of the asylum seeker as claimant is essential to the legal process. It is the claim that initiates the possibility of recognition and protection. In making the claim, the asylum seeker does negotiate the established boundaries of the refugee definition by attempting to conform or fit within those boundaries, but the claim is also a demand that the boundaries be moved and the definition expanded if and when that is what is necessary for recognition and protection of this person. The demand that the boundaries be negotiated is not aberrational; it is intrinsic to the process. The demand that the boundaries be negotiated is neither fraud nor abuse; it is the very possibility of asylum.

The demand does not, of course, determine how receiving states and societies will respond. Recognizing the asylum claim as an act of moral agency that demands a negotiation of who should receive recognition and protection does, however, implicate receiving states and societies in the negotiation. A clear and bounded refugee definition can be morally comforting for receiving societies, not just the tool of governments intent on restricting asylum. Christian ethicist Luke Bretherton, echoing many scholars and policymakers who have argued for careful delineation of the refugee definition, has written:

While there is much to be said for broadening the definition to take account of contemporary geo-political realities, the crucial point to keep sight of is that, in order to be of any critical or practical use, the definition needs to be able to distinguish the moral status and claims of refugees from other categories of those in need in order that the appropriate forms of care can be given and the specific need met.18

When the asylum claim renegotiates the boundaries of the refugee definition it also renegotiates receiving societies’ responsibilities and obligations. Perhaps the crucial point is not, as Bretherton suggests, to have a clear understanding of the criteria to which asylum seekers must conform in order to have a legitimate claim to asylum. The crucial point may be hearing and understanding the demand for recognition that is contained in the asylum seeker’s claim, as well as the experiences and convictions that animate that claim. The crucial point may be participating in the renegotiations, which requires being open to shifting boundaries, not looking for a better place to fix them. That may be the only way to provide the appropriate forms of care and ensure that specific needs are met.

My thanks to all of the participants in the Moral Agency under Constraint seminar for their feedback and input during the development of this essay. My thanks as well to Don Kerwin for valuable comments on a prior draft.

Do you want to know more about this author? Click here!

Footnotes

- Ada Limón, “Sharks in the Rivers,” in Sharks in the Rivers (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2010).

- For a more detailed recounting of Aminta Cifuentes’s experience, see Julia Preston, “In First for Court, Woman Is Ruled Eligible for Asylum in U.S. on Basis of Domestic Abuse,” The New York Times, August 29, 2014, sec. U.S., https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/30/us/victim-of-domestic-violence-in-guatemala-is-ruled-eligible-for-asylum-in-us.html.

- Matter of R-A-, 22 I&N Dec. 906 (BIA 1999) (en banc), vacated, 22 I&N Dec. 906 (A.G. 2001), remanded, 23 I&N Dec. 694 (A.G. 2005), remanded and stay lifted, 24 I&N Dec. 629 (A.G. 2008).

- See Matter of A-R-C-G-, 26 I&N Dec. 388, 391–92 n.12 (BIA 2014).

- Matter of A-R-C-G-, 26 I&N Dec. 388 (BIA 2014).

- It is important to note that the immigration courts, known formally as the Executive Office of Immigration Review, are not part of the independent federal judiciary; rather, the immigration courts operate within the Department of Justice and under the authority of the Attorney General. One of the powers conferred on the Attorney General in this arrangement is the ability to refer cases to itself for adjudication. 8 C.F.R. § 1003.1(h). The referral power allows the Attorney General to intervene in cases for the purpose of setting immigration policy.

- Matter of A-B-, 27 I&N Dec. 316 (A.G. 2018).

- See Jeff Sessions, “Remarks to the Largest Class of Immigration Judges in History for the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR)” (Falls Church, VA, September 10, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/attorney-general-sessions-delivers-remarks-largest-class-immigration-judges-history; Jeff Sessions, “Remarks to the Executive Office of Immigration Review” (Falls Church, VA, October 12, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/attorney-general-jeff-sessions-delivers-remarks-executive-office-immigration-review.

- The same legal definition is applied to both refugees and asylees. The difference between the two is a matter of the process by which their claim is adjudicated. See Department of Homeland Security, “Refugees and Asylees” (last updated January 9, 2020), https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/refugees-asylees.

- For a critique of aquatic metaphors, see Michael Diedring and John Dorber, “Refugee Crisis: How Language Contributes to the Fate of Refugees,” The Elders, October 27, 2015, http://theelders.org/article/refugee-crisis-how-language-contributes-fate-refugees.

- Chae Chan Ping v. United States, 130 U.S. 581, 631 (1889); see also, R v. Immigration Officer at Prague Airport [2004] QB 811, at para. 12 (opinion of Lord Bingham) [England].

- For two excellent histories of exclusionary practices in U.S. immigration law, see Aristide R. Zolberg, A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America (Harvard University Press, 2009), and Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014).

- Although, the golden ticket system also fails many others in many ways. As only one example, Donald Kerwin and Robert Warren have written about the dysfunction of family-based asylum in the United States, and the long waits many immigrants endure to reunite with family. Donald Kerwin and Robert Warren, “Fixing What’s Most Broken in the US Immigration System: A Profile of the Family Members of US Citizens and Lawful Permanent Residents Mired in Multiyear Backlogs,” Journal on Migration and Human Security 7, no. 2 (2019): 36–41, https://doi.org/10.1177/2331502419852925.

- Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, July 28, 1951, 189 U.N.T.S. 137; Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, art. 1(2), Jan. 31, 1967, 606 U.N.T.S. 267. In the United States, the Refugee Convention was incorporated into domestic law by the Refugee Act of 1980, 94 Stat. 102.

- 1951 Convention, art. 1(A)(2), as amended by 1967 Protocol, art. 1(2) (emphasis added).

- Andrew Schoenholtz has argued that the evolutionary potential of the refugee definition “enables adjudicators to take into account societal changes as well as persecutory forms of discrimination of which the treaty negotiators were unaware. In short, the terms possess adequate flexibility to adapt to changed circumstances.” Andrew I. Schoenholtz, “The New Refugees and the Old Treaty: Persecutors and Persecuted in the Twenty-First Century,” Chicago Journal of International Law 16, no. 1 (2015): 107–08.

- While Sessions was forced out as Attorney General in 2018, these policies were continued by his successor, William Barr, and other members of the Trump administration.

- Luke Bretherton, “The Duty of Care to Refugees, Christian Cosmopolitanism, and the Hallowing of Bare Life,” Studies in Christian Ethics 19, no. 1 (2006): 42, https://doi.org/10.1177/0953946806062268.