Abstract:

Cultural norms and historical events have shaped and changed the way in which individuals have viewed and accessed their food. One food in particular that has impacted society and food consumption is instant noodles. Despite its popularity and inexpensive accessibility, few individuals know the historical context and impact that Ramen noodles have had across the globe. This paper explores the origin, history and evolution of Ramen noodles and how these noodles have impacted society as a whole.

If you look in the pantry of nearly every household around the world, you will find a small rectangular packet of instant noodles. These twenty-five cent packages are now a cheap and easy way to fill hungry stomachs. However, ramen noodles were not always inexpensively available, these noodles were once considered a luxury item. People from many different socio-economic backgrounds have tried this dish and despite the low nutritional value and high amount of sodium, continue to consume it. Its versatility is something that is extremely valued around the world. Some people eat it as the package describes but others may decide to drain the broth, add egg, sausages, or spinach. Other people may throw away the seasoning packet and use the noodles in a stir fry or throw away the noodles and use the seasoning in another dish. People’s ability to be creative with this very simple and easy product is something that attracts consumers to throw in a couple of packs every time they run to their local grocery store. Although it originated in a single country, instant noodles have spread far and wide around the world and even into outer space. Ramen noodles have even become such a staple for poor college students. What made this revolutionary food the go-to for every college student all over the world?

Originating in Northwest China, Ramen was introduced to Japan in the late 19th century. There are many speculations as to the true introduction of ramen to Japan. Some theories suggest that it was introduced by Chinese tradesmen at the Yokohama port in Japan and others say that it was presented to Japan during the 1660s by the Chinese scholar Zhu Shunsui who became a refuge in Japan to escape the Manchu rule in China. Regardless, the ramen noodle dish easily became a large staple of the

Japanese cuisine. Until 1950, ramen was referred to as Shina Soba which translates directly to Chinese Soba. The word Shina now has a derogatory connotation that prompted the switch to the term Chüka soba or as we know it now, ramen. The Japanese word ramen came from the Chinese words for pull (la) and noodle (mian). This is because Chinese people were known to pull noodles by hand. In many countries, the name ramen and instant noodles are interchangeable but their creation and ingredients differ greatly.

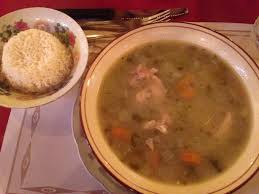

It is important to point out the difference between ramen and instant noodles. Ramen is usually made of hand-pulled wheat noodles in pork, chicken or miso broth topped with meat, scallions and many other types of vegetables. There are many variations of ramen which include egg, edamame, bamboo shoots and more. The noodles are made out of wheat flour, salt, water and kansui, a sodium-carbonate-infused alkaline mineral water. Eggs are often used as a substitute for the kansui. They are created and served fresh with little to no preservatives involved. Instant noodles, on the other hand, are dried and not known to come with any type of meat or vegetables. Today, instant noodles are sold at a much cheaper price than ramen and require less work to create.

In 1958, instant noodles were invented by Momofuku Ando as a dehydrated version of the typical ramen called “Chikin Ramen” as a way to combat starvation caused by World War II. Japan experienced its worst rice harvest recorded in 42 years after their defeat in World War II and the American military occupied the country. This harsh decline of such a filling staple of Japanese cuisine caused a drastic food shortage. The United States then flooded Japan with cheap wheat flour to combat the food shortage.

The wheat was made into bread along with ramen noodles. After tirelessly working on this idea to revolutionize ramen, he found that dehydrating the noodles and then flash-frying them in palm oil allowed for them to stay on the shelves for longer and be quickly reheated. Instant noodles were first created with the noodles being pre-seasoned but due to the high demand for a better taste, the flavoring powder was put in a separate packet. The instant noodles were sold at a slightly higher price than ramen which is why it was at one time considered a luxury food item. Opposed to traditional ramen, the instant ramen is now manufactured with a vast amount of additives such as viscosity stabilizers, preservatives, emulsifiers, antioxidants, color, and fortifier dietary supplements. Then in 1971, “Cup Noodles” were created as an easy way to eat without the need for cookware and tableware. The Styrofoam cup served as the packaging material, the cooker, and the bowl. The instant noodles do contain the traditional

kansui seasoning that allows for the unique flavor that people value so much but as far as added vegetables and meat, only the cup noodles contain freeze-dried garnishes.

In 1970, Nissin Foods, run by Momofuku Ando, brought instant noodles to the United States of America. From the beginning, instant ramen has been sold in local stores for twenty-five cents and comes in bulk for even cheaper. This is particularly appealing to low-income families and cost-conscious college students. Ramen is also used in food aid packages and is donated to disaster-stricken places around the world due to its low price and ability to satisfy hunger. The low price isn’t purely found in the United States but also many countries all over the world. Each with their own rendition of the flavor of the noodle and the company that it sold from. In Thailand, MAMA noodles are the most popular type of instant noodles and it is tailored to the Thai culture by the flavors sold, such as Tom Yum (a traditional Thai lemongrass soup) and green curry flavor. In Mexico, Maruchan is the top brand of instant noodles and their flavors of lime and chili are the most popular as it created to appeal

to the audience.

The popularity of Top Ramen brought forth many imitators who also wished to reap the success of such a booming food source. These brands include Maruchan, MAMA, Hao Hao, Samyang Ramen and more. Understanding business and fear of quality issues from other manufacturers, Momofuku Ando created the International Ramen Manufacturers Association (IRMA) as a platform for global food safety of the instant noodles. The association created an index in which all instant noodle manufacturers and manufacturers of similar items must follow in order to continue making and distributing instant noodles. The company is now known as the World Instant Noodles Association (WINA). There are many variations of the original Top Ramen brand and along with the increased health focus of the general population, instant noodles that have less sodium or no MSG were created. These healthy alternatives, although more expensive than the expected twenty-five cents, provide the same noodle for better health benefits.

Today, ramen is one of Japan’s most popular foods with more than 24,000 ramen restaurants across Japan. However, despite the popularity in the instant noodles’ place of origin, Japan is ranked number four by the World Instant Noodles Association in its consumption of instant noodles following, China, Indonesia, and India. The World Instant Noodles Association was created to combat the ever-growing awareness of the unhealthiness of instant noodles. Each serving of instant noodles contain nearly 200

calories per serving and 861 mg of sodium, and each packet contains two servings. Although the number of calories may not be too concerning, the amount of sodium that is ingested in one packet of instant noodles may cause an increase in blood pressure which can increase the risk of obtaining cardiovascular diseases and events. Historically, African Americans have developed a high sodium diet through their generational low-socioeconomic backgrounds. Higher amounts of seasonings were used to make low-cost items taste better. It is a known fact that African-Americans are genetically more prone to high cholesterol and hypertension. There are also more African-American low socio-economic households, which are primarily located in food deserts. The easy access of instant noodles and fast preparation is something that is cherished in low-socioeconomic homes and its harmfulness to health is something that would primarily affect African-American people. Frequent consumption is linked to increased risk of metabolic syndrome, heart disease and decreased diet quality. Despite its constant negative connotation with health, instant noodles have been sent to cities all over the world to help lack of food from environmental disasters. The World Instant Noodles Association has sent emergency food aid to Indonesia after the 2018 tsunamis and earthquakes, the Philippines after Typhoon “Mangkhut”, and even to North Carolina after Hurricane Florence. It’s ability to be created into hunger-satiating

meals with just the addition of water is a quality that not many other foods have. Instant noodles are also able to be transported with little to no effort as it is lightweight and has a long shelf life, which makes it an ideal meal for people that need filling food quickly.

Instant ramen even made their way into space. In 2005, instant noodles combined their effort with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to create ramen that could be eaten in space. Three small noodle cakes, broth, and condiments were put into soft airtight bags and loaded onto a space shuttle. The noodles were designed to be cooked without being boiled and the broth was designed to be thick enough to keep it dispersing in the gravity-free environment. The technological advancements that led to such an innovation is further proof of instant noodles’ success has expanded across the globe and even into the atmosphere.

The simplistic nature of instant noodles is something that is cherished by people all over the world. From the healthier and fresher roots of ramen, instant noodles have become revolutionized to become easier by compromising its nutritional values. It is also an important resource for people who do not have food readily available or do not have the time to dedicate to more complicated meals. Although it is not an item that many would pick first and more often seen as a back-up to a meal or a snack,

for some, it is all that they have to survive. Having traveled to space and back, it can be seen that instant noodles are more than just starch in a bright flavored packaging. It has fed millions of people experiencing trauma that others may never begin to imagine.

Works Cited

Timeline_Now. “How Ramen Took over the World.” Medium, Timeline, 29 Nov. 2016, timeline.com/ramen-path-global-domination-b4d9831dbce.

Barclay, Eliza. “Ramen To The Rescue: How Instant Noodles Fight Global Hunger.” NPR, NPR, 20 Aug. 2013, www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2013/08/16/212671438/ramen-to-the-rescue-how-instant-noodles-fight-global-hunger.

Bratskeir, Kate, and Kristen Aiken. “So How Bad Is Ramen For You, Anyway?” HuffPost, HuffPost, 7 Dec. 2017, www.huffpost.com/entry/ramen-nutrition-information-salty_n_5621918.

“Cup Noodles Museum Museum about Instant Cup Noodles.” Yokohama Travel: Cup Noodles Museum, www.japan-guide.com/e/e3212.html.

“FAQs.” FAQs | World Instant Noodles Association., instantnoodles.org/en/noodles/faq.html.

“Instant Noodle.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 8 Aug. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instant_noodle.

Johnson, Carolyn. “The Global Power of Instant Noodles – The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com, The Boston Globe, 8 Sept. 2013, www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2013/09/08/the-global-power-instant-noodles/slwhJDp9yoE6M5C1uokrlJ/story.html.

Leibowitz, Karen. “The Humble Origins of Instant Ramen: From Ending World Hunger to Space Noodles.” Gizmodo, Gizmodo, 18 June 2013, gizmodo.com/the-humble-origins-of-instant-ramen-from-ending-world-5814099.

Link, Rachael. “Are Instant Noodles Bad for You?” Healthline, Healthline Media, 15 Apr. 2017, www.healthline.com/nutrition/instant-noodles#section7.

Mills, Shannon. “The Dangers of Instant Noodles.” Lifehack, Lifehack, 7 Feb. 2016, www.lifehack.org/361298/what-will-happen-your-body-when-you-eat-instant-noodles.

“Ramen.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 7 Aug. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramen.

“The Real Difference Between Instant Noodles and Ramen.” Spoon University, 7 July 2017, spoonuniversity.com/lifestyle/ramen-and-instant-noodles.

Rufus, Anneli, and AlterNet. “The Strange History of Ramen Noodles.” Alternet.org, 24 July 2012, www.alternet.org/2011/06/the_strange_history_of_ramen_noodles/.