The Many Reflections of the Noodle

A 2002 archaeological study in the Qinghai Province left people stunned when archaeologists stumbled upon a 4,000-year-old bowl of noodles on the Chinese archeological site. Many would think that this finding would be conclusive in determining that China was where the noodle originated because it is said to be the earliest noodles ever found, yet there is still debate as to which country really founded this edible cultural artifact. This continued debate shows how the noodle is a source of cultural pride, something that would give whatever country or region of the world it came from bragging rights essentially. Some think the noodle came from Italy, others believe it came from China, and there are some that believe it came from the Middle East. Regardless of whichever country invented noodles however, both China and Italy should be extremely proud of the noodle dishes they have maintained over many hundreds of years, or as people from the Western Hemisphere like to call “pasta” dishes. The noodle reflects the culture, regions, cities, and people that cook them in these countries and plays a very integral role in the food culture of both China and Italy. With the cultural and regional importance attached to noodles, it is understandable as to why the birthplace of noodles is still so hotly contested.

Culture consists of many aspects such as language, religion, fashion, customs, and as the basis of this paper—food. Both Chinese and Italians are very food-centered people, so food happens to be a very large part that makes up their cultures, and is also a primary source of enjoyment and pleasure in life. The noodle is continuously referred to as a culture bearer, conveying information about cultures and being the rare cultural artifact that we actually put into us. Variability of food, such as varying shapes and compositions of noodles, is not necessary for human survival, but humans partake in such variability anyways, and there is variability amongst these variabilities in food around the globe at least partly due to cultural differences (https://asiasociety.org/blog/asia/food-chinese-culture). What Chinese see as “human nature” or cultural traditions and “worldly common sense” or customs are reflected through noodles (Zhang and Ma 209). In China, a common greeting is “Have you eaten today?” and a compliment is “You look fat,” both comments probably being seen as odd in Western culture but normal in Chinese culture. Though there is a strong focus on food in China, overindulgence in food is frowned upon, according to Chang’s Food in Chinese Culture: Anthropological and Historical Perspectives. Food is greatly valued for its medicinal properties in China, thus food acts as a substitute for medicine oftentimes, showing a cultural preference for natural products rather than pharmaceutical products. With this focus on the medicinal properties of food, there is a large focus on health in China. This focus on health can be seen with the longevity noodle in China—on a birthday, Chinese will customarily take the longest noodle from their bowls and place it in the bowl belonging to the person celebrating their birthday in order to give them a long, healthy life due to the longest noodles being in his or her bowl. In Italy, if continuing tradition, daughters and granddaughters will help make the spaghetti gravy for a big Sunday lunch starting on Friday to give the gravy time to cook and will help in the process of making the pasta at home also. There is a big emphasis on family in the Italian culture and the time-consuming process of making pasta at home gives an opportunity for more familial time between the generations of women in a family and the big Sunday lunch in which the pasta is being made for allows the family, males and females, to all gather together at the table and eat while discussing recent events in their lives and taking the time to reconnect in a way.

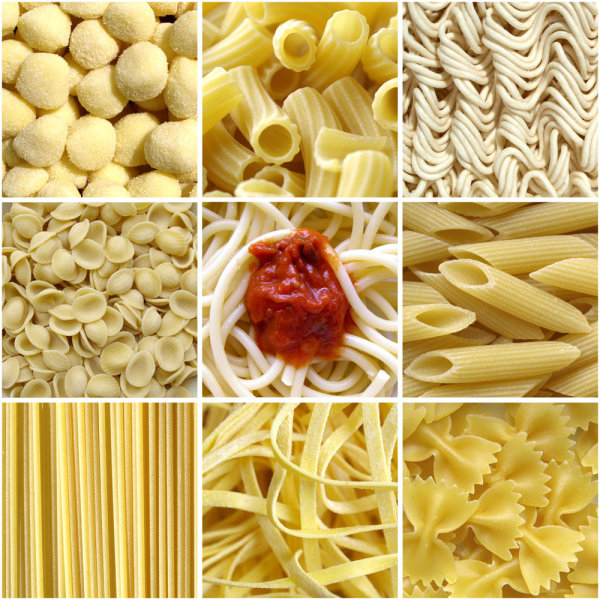

The noodle also reflects the region in which it is cooked. There is a wide variety of regional food, noodle dishes included, in China and Italy due to the regions of both countries having a history of invasions, foreign influences, and geographical factors that affect agriculture. Region is one component that goes into how noodles are categorized. All twenty regions of Italy have different types of pasta from each other. In China, the Eastern region has a different set of noodles from the other Chinese regions including “Shanghai noodles in superior soup (上海阳春面), Nanjing small boiled noodles (南京小煮面), Hangzhou Pian Er Chuan noodles (noodles with preserved vegetable, sliced Pork, and bamboo shoots in soup) (杭州片儿川面), Wenzhou vegetable raw noodles (温州素面), Zhenjiang pot noodles (镇江锅盖),” and “Shandong Fushan hand-pulled noodles (山东福山拉面),” while Northern China has a different variety of noodle dishes such as “Beijing fried bean sauce noodles” and “Shanxi shaved noodles (山西刀削面)” (Zhang and Ma 211). Wheat noodles are more commonly eaten in northern China while rice noodles are more commonly eaten in southern China due to agricultural differences. Rice is primarily grown in the southern part of China and wheat is grown in the northern part of China, both of which are used to make noodles, and this difference in agriculture led to a difference in behaviors. The southern Chinese are much more interdependent and cooperative than northern Chinese because of how labor-intensive growing rice is according to Thomas Talhelm’s Rice Theory. The flat plains of northern China are conducive for growing wheat and the many rivers and lakes in southern China are conducive to growing rice. There are different types of pasta and sauce pairings depending on region, too. Penne can either be smooth or have ridges depending on the region it is cooked in and what sauce is being paired with it. Italy has such diversification in regions due to being separate for a large part of the country’s development and thus developing different dialects that the same noodle or pasta dish can go by different names depending on the region, such as lombricelli with its 28 different names.

Noodles reflect cities because “[m]any noodles have local characteristics” (Zhang and Ma). Each city has its own cuisine partly because each city has different fresh local products because of geographical factors like landscape and location on the globe. Each of Italy’s cities is unique, consisting of their own food, community, and ways of doing things due to Italy not being a unified country for a long time, so there is still an essence of campanilismoin Italy, meaning local patriotism, each believing that they make the best noodle dishes and each with one they are known for.

The noodle reflects the perseverance of people that cook them due to the hard work that goes into making noodles, as illustrated by the old couple in China waking at 3 in the morning to start making them and only finishing at 9 in the evening (A Bite of China). As noodles are a source of pride for both Italy and China, the cooking of noodles provides a sense of dignity to those that cook them. Noodles are very versatile and adaptable, so they can be changed very easily when cooking, affecting tastes and feel and reflecting the preferences of those cooking them (Slippery noodles)

Noodles, being as versatile as they are, can mean different things for different people. Though noodles are often eaten in China, noodles seem to mean “celebration” and “honor” for Chinese. Noodles are a source of nourishment and nutrition, while also being used as a means of celebration in China, such as with the Lantern Festival and the Dragon Boat festival. Noodles are also used to honor gods, spiritual beings, and both living and dead loved ones. For example, seafood noodles are also known as dutiful son noodles. Giaza, a type of noodle, literally means “the end and the beginning,” but figuratively means family reunion for many Chinese. Much like each character means something different in China, each noodle dish has a different meaning behind it. The heat of the fine egg noodle dish supposedly keeps bad spirts away in the story, “Crossing the Bridge” (Durack 183). Noodles seem to also mean honor in Italy and love. A key theme in the Italian dish, Strega Nona, is that the elderly are seen as authority figures, thus honoring the elderly with this key theme. Noodles seem to also mean love in Italy because food is a way of dialogue between people, being how they display love for one another by joint eating of food and/or cooking of food for someone. Food and drink are a way for Italian people to spend time together, allowing them to have a vocal dialogue but also a silent dialogue of love through noodles.

Noodles play an integral role in both China and Italy’s dietary patterns. As Zhang and Ma said, “noodles are a kind of cereal food,” being “the main body of the traditional Chinese diet” and “the main source of energy for Chinese people and the most economical energy food” (Zhang and Ma 209). Noodles are meant to avoid the disadvantages that come with a low carbohydrate, high energy, and high fat diet and thus promote health, according to Zhang and Ma (209). Noodles hold a high status in the dietary structures of both China and Italy. In the Mediterranean diet, hard grains are held on a high pedestal and many Italians thus try to make pasta from hard grains, making pasta an essential part of the Mediterranean diet. Chef Gurelli says that “It’s beautiful. They (Italy) tamed the sea and land to grow what they want” but sometimes you’re limited to the land and geographical region you’re in which leads to the development of certain foods fitting for your region due to the growth of crops—more so, it’s beautiful they created beauty out of simplicity; “Highlighting the importance of this traditional dietary pattern, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recognizes the Mediterranean Diet as an element of intangible cultural heritage. Health experts affirm the role of pasta in nutritious, Mediterranean-inspired eating patterns” (p. 6, The Truth About Pasta).

Noodles are defined as a basic global staple food made from durum wheat semolina or other flours “mixed with water and/or eggs to make a dough” in The International Pasta Organization’s book of pasta (p. 5, The Truth About Pasta). Though, I would define noodles as being more than their components and instead as a bridge—they act as a bridge covering gaps between people by allowing them to bond and also as a bridge to the past, one that connects people to their ancestors and history.

I designed a DNA strand consisting of 15 different types of Chinese and Italian noodles—the pulled noodle; rigatoni noodle; dandan noodle; campanelle noodle; rice noodle; macaroni noodle; penne noodle; udon noodle; linguine noodle; longevity noodle; reginette noodle; Henan stewed noodle; Kunshan Ao Zao noodle; hot dry noodle; and trofie noodle. The DNA strand made of noodles represents how noodles are an integral part of one’s cultural DNA. The noodles, which are supposed to look like they are intertwining in the DNA strand, are also meant to show the link between China and Italy in terms of noodles due to China being the likely originator of noodles and their subsequent travel to Italy. The different noodles meet together in the DNA strand to show the similarities of a deep love for noodles and having food-centered cultures in both China and Italy.

Noodle (click here to see PDF image)

Culture is reflected in the noodles of both China and Italy, but with globalization and commercialization, the noodles have managed to wrap themselves around the globe and the traditional noodle dishes begin to slowly lose their cultural authenticity. People eat them and may recognize them as Italian or Chinese, but many do not understand the culture of those countries that is imbued in the noodles, thus not understanding the significance of the dishes.

Works Cited

(2014) A Bite of China 02 The Story of Staple Food(HD). In: YouTube. https://youtu.be/B8lTWruUaQc. Accessed 25 Jul 2019.

(2013) BBC – Italy Unpacked: The Art of the Feast. In: YouTube. https://youtu.be/BW9-b3J3-DY. Accessed 24 Jul 2019.

Canadian Journal of History. In: Canadian Journal of History. https://www.utpjournals.press/doi/abs/10.3138/cjh.13.1.103?journalCode=cjh. Accessed 27 Jul 2019.

(2018) Chicken Stir Fry with Rice Noodles. In: Salt & Lavender. https://www.saltandlavender.com/chicken-stir-fry-rice-noodles/. Accessed 27 Jul 2019

Corn, Bacon, and Egg Pasta – Video Recipe. In: FineCooking. https://www.finecooking.com/recipe/corn-bacon-and-egg-pasta. Accessed 27 Jul 2019

Dan Dan Noodles. In: Spice Mountain. https://www.spicemountain.co.uk/recipe/dan-dan-noodles/. Accessed 27 Jul 2019

Dried linguine and rigatoni pasta on a wooden surface. In: 123RF. https://www.123rf.com/photo_22829361_dried-linguine-and-rigatoni-pasta-on-a-wooden-surface.html. Accessed 27 Jul 2019

Durack T (2001) Noodle. Pavilion, London.

Eat North (2019) Parcheggio’s Rigatoni Alla Carbone. In: Eat North. https://eatnorth.com/eat-north/parcheggios-rigatoni-alla-carbone. Accessed 27 Jul 2019

Food in Chinese Culture. In: Asia Society. https://asiasociety.org/blog/asia/food-chinese-culture. Accessed 26 Jul 2019

Staff LVB (2011) Witness the Art of the Hand-Pulled Chinese Noodle. In: Las Vegas Blog. http://blog.caesars.com/las-vegas/las-vegas-hotels/caesars-palace/witness-the-art-of-the-hand-pulled-chinese-noodle/amp/. Accessed 27 Jul 2019.

Limited A Stock Photo – Famous noodles in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, China, have many flavors. In: Alamy. https://www.alamy.com/stock-image-famous-noodles-in-suzhou-jiangsu-province-china-have-many-flavors-166196904.html. Accessed 27 Jul 2019

The Stone’s Hot Dry Noodles, Wuhan – Restaurant Reviews & Photos. In: TripAdvisor. https://www.tripadvisor.com/Restaurant_Review-g297437-d3480710-Reviews-The_Stone_s_Hot_Dry_Noodles-Wuhan_Hubei.html. Accessed 26 Jul 2019

Wine Dharma. In: Basil pesto pasta: how to make the authentic italian recipe | Wine Dharma. https://winedharma.com/en/dharmag/may-2016/basil-pesto-pasta-how-make-authentic-italian-recipe. Accessed 27 Jul 2019

Thongchaipeun Italian pasta (macaroni) stock photo. Image of food, macro – 34958744. In: Dreamstime. https://www.dreamstime.com/stock-images-italian-pasta-macaroni-isolated-white-background-image34958744. Accessed 27 Jul 2019

Penne With Vodka Sauce. In: Food Network. https://www.foodnetwork.com/recipes/food-network-kitchen/penne-with-vodka-sauce-recipe-1973607. Accessed 27 Jul 2019

Savita Easy Stir Fry with Udon Noodles – Stir Fry Noodles Recipe. In: ChefDeHome.com. https://www.chefdehome.com/recipes/123/stir-fry-udon-noodles. Accessed 27 Jul 2019

Sippitysup, David, Paulina, et al (2019) Chinese Longevity Noodles Recipe. In: Cooking On The Weekends. https://cookingontheweekends.com/chile-spiced-chinese-noodles-recipe/. Accessed 27 Jul 2019

Reginette con pesto rosso *** Reginette pasta with red pesto sauce. In: Home Italian Recipes. http://homeitalianrecipes.com/reginette-con-pesto-rosso/. Accessed 27 Jul 2019

Zhang N, Ma G (2016) Noodles, Traditionally and Today. Journal of Ethnic Foods 209–212.

Lin HJ (2015) Slippery noodles: a culinary history of China. Prospect Books, London

The Truth About Pasta: One Food, One Love. In: International Pasta Organization. https://oldwayspt.org/system/files/atoms/files/TruthAboutPasta16.pdf.