By Ambika Natarajan

As with many wars, the origin of the Syrian Civil War can technically be traced to one concrete starting point—fifteen boys in Dara’a, Syria, spray painted the words “The people want the fall of the regime” on a school wall in 2011 (Laub 2020). The boys were captured and tortured, sparking unrest throughout the country. While the war was initially between the Al-Assad regime and the opposing Free Syrian Army, multiple entities, including different factions of Al-Qaeda, Hezbollah, Turkey, Russia, and the United States, were all involved (Laub 2020). The region has become totally destabilized, with around 400,000 casualtiessince the war’s onset, 6.2 million internally displacedand 5.6 million registered refugees, according to the Council on Foreign Relations (Global Conflict Tracker).

While political dissent was a visible factor in the region’s destabilization, in 2015, major media outlets such as Scientific American, PBS News Hour, and National Geographicpublished on the possibility of there being an additional contributor — climate change. The headlines ran, “Climate Change Hastened Syria’s Civil War,” “A Major Contributor to the Syrian Conflict? Climate Change” and “Climate Change Helped Spark Syrian War, Study Says,” respectively (Fischetti 2015, Mansharamani 2016, Wlech 2015). Climate change’s pre-existing reputation as a potential “threat multiplier” neatly affirms the underlying story within these articles. They all claim that anthropogenic emissions caused a prolonged drought in Syria that has decreased agricultural yields and encouraged migration towards the cities, prompting unrest. Perhaps given the novelty and strength of a climate war as a supporting example of the perils of climate change, the messages that the media carries miss the complex nature of the drought and its potential impact on the region’s conflict.

Additionally, most of the media articles rely on a single study performed by scientists of UC Santa Barbara and Columbia University’s School of International Affairs and Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, titled “Climate change in the Fertile Crescent and implications of the recent Syrian drought,” which was published in 2015 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States ofAmericaand has been cited over 1150 times as of April 6, 2021 (Kelley 2015). The study uses climate models to demonstrate the presence of climate change in Syria and then states that climate change may have exacerbated a drought that prompted the country’s debilitating conflict. However, less-recognized papers have contributed to the discussion by questioning the scope of the climate study and presenting more rigorous studies of natural and sociopolitical factors contributing to reduced water availability and agricultural output. The media’s highlighting of a single high-impact study rather than a comprehensive literature review on the relationship between climate change and the conflict in Syria can misinform public perceptions on the impacts of climate change.

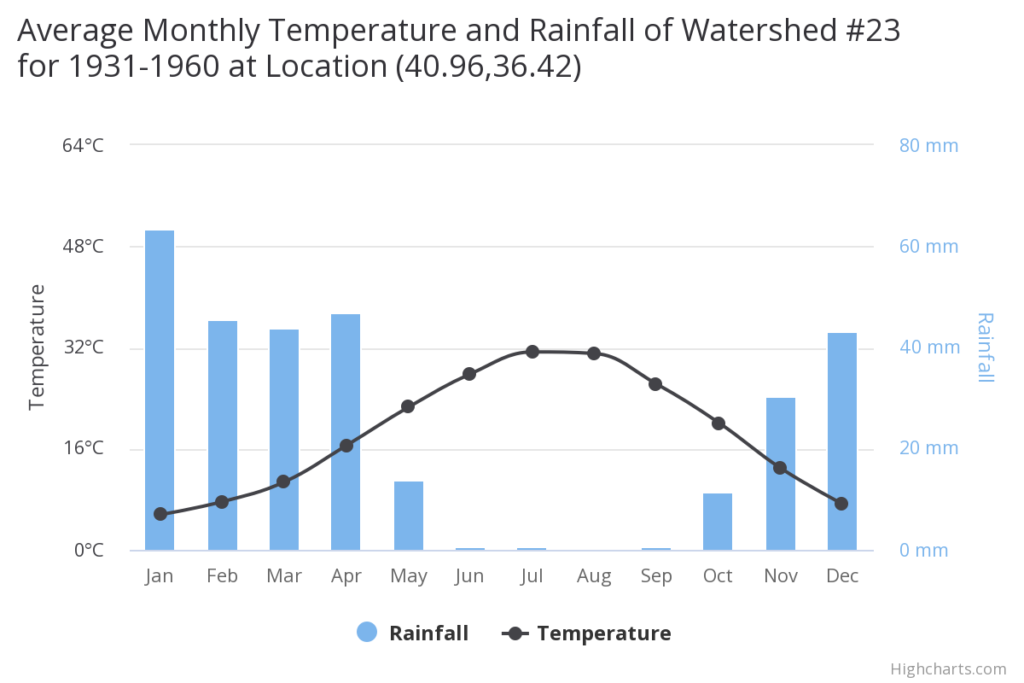

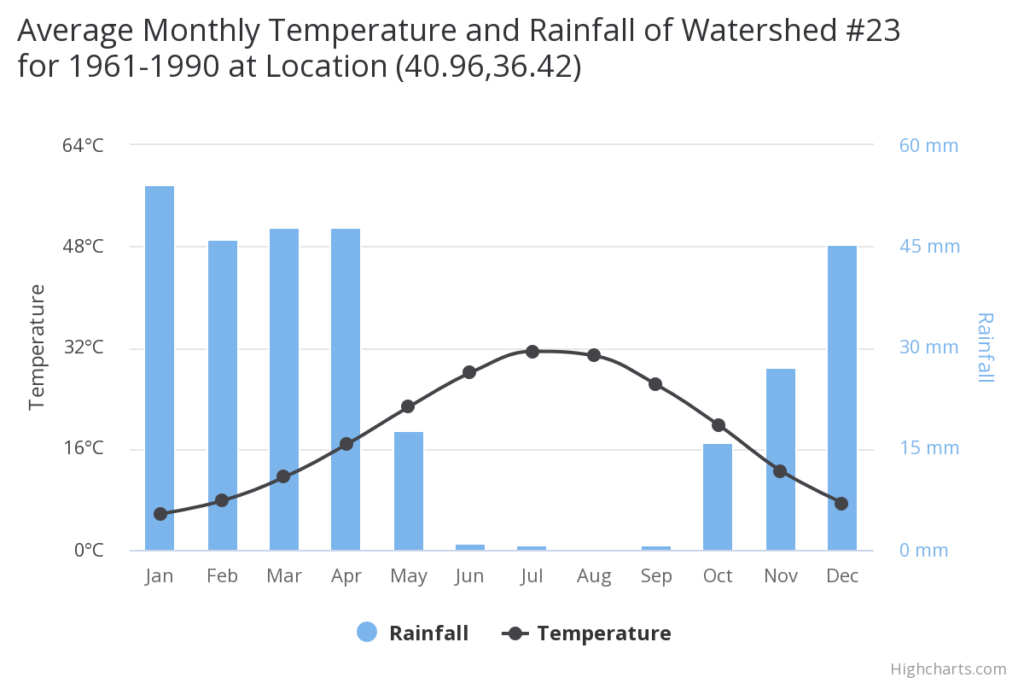

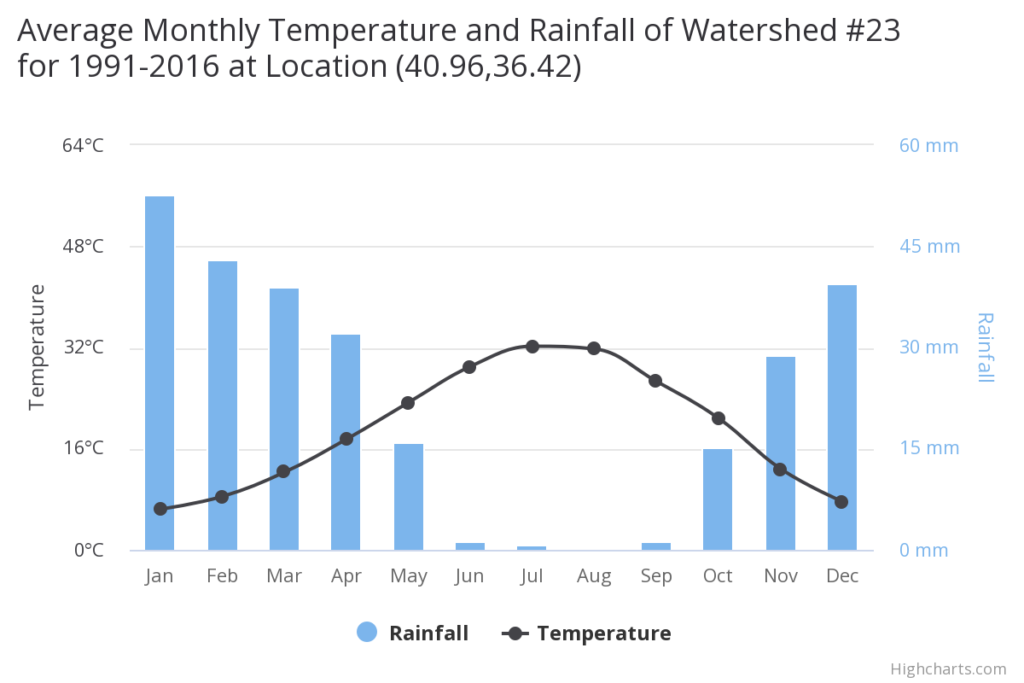

The main strength of the paper by Kelley et. al. (2015) is its climate change study, which is conducted for the entire country of Syria. It availed of Climatic Regional Unit (CRU) 3.1 data to map precipitation levels and near-surface temperature levels between 1900 and 2008. A linear least-squares fit was established for both models, revealing the steady downward trend in precipitation and an upward trend in near-surface temperatures that would be characteristic of climate change impacts. Deviations in specific humidity are also reported for the period of 1989 to 2008 with respect to the period between 1931 to 1950, highlighting Western Turkey as the epicenter of the drying trend with parts of Iraq, Syria and Iran also experiencing similar effects. Additionally, the paper combined the factors into a Palmer Severity Drought Index to visualize the region’s growing tendency towards drought. This phenomenon was further supported by computational and observational data assessing the extent of CO2forcing in Syria, corroborating the role of anthropogenic emissions on the extreme weather effect. Indeed, the drought in Syria between 2007 and 2010 was the worst 3-year drought to be recorded within the region.

The treatment of the drought’s relationship to the conflict is stated blatantly in the abstract of the paper by Kelley et. al. (2015), which names climate change as a “catalyst” for the ensuing “political unrest.” The connection moves the paper away from concrete science and towards a geopolitical narrative, connecting climatic studies to a societal outcome. This becomes a source of contention, as the intermediate actors of agriculture and water management and politics are also complex. The authors acknowledge the increase in agriculture prompted by reforms under Hafez al-Assad, the over-extraction of groundwater, and the over four-fold growth of the total population of Syria since 1950. At the same time, these factors are not incorporated into the quantitative nature of the study. The paper’s conclusion asserts strongly that human-induced climate change contributed to Syria’s agrarian collapse and subsequent migration, and more tentatively that the government’s inability to respond to the needs of those displaced sparked conflict. A more rigorous examination of the variables contributing to agricultural decline, water loss, and conflict, must be presented before drawing a direct conclusion regarding the impacts of climate change in a single case study.

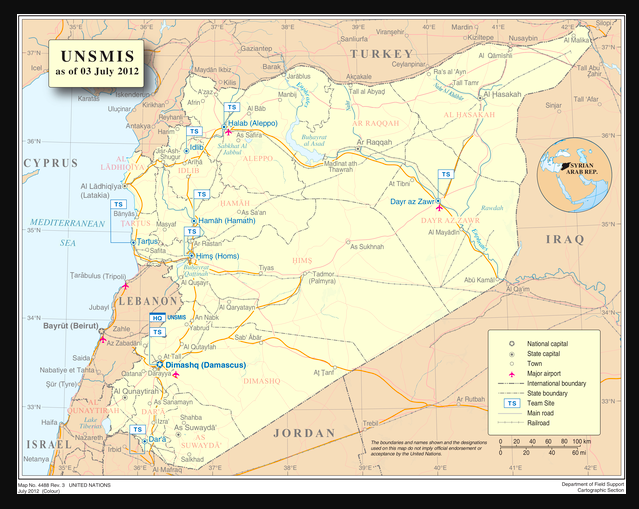

The most prominent rebuttal to the climate-conflict connection in Syria was issued by scientists of the University of Sussex, Hampshire College, the University of Hamburg, and King’s College London in the paper titled, “Climate Change and the Syrian Civil War Revisited,” which was published in Political Geography in 2017 (Selby 2017). The study was picked up by Reuters, but otherwise lacked substantial media coverage (Arsenault 2017). The paper acknowledges that the study by Kelley et. al. (2015) is well-known for its documentation of the case study given its incorporation of climate models. It emphasizes that although climate change may have contributed to the drought, the magnitude of its impact may be significantly less than that of other factors (Selby 2017). The paper first assesses the scale of the Syrian drought at local and regional levels, in contrast to the study by Kelley et. al. (2015) that looked at Syria as a whole. The findings show that northeast Syria did indeed experience the lowest records of rainfall on record for that region, but the cities of Aleppo, Damascus, Homs and Dara’a witnessed above-average or average levels of rainfall. Northern Iraq also saw a relatively greater decline in rainfall than northeast Syria, affirming that the location from which migration was observed was not necessarily the epicenter of the drought. The authors go further to suggest that the linear regression method of assessing dryland rainfall, used by Kelley et. al. (2015), has been proven inefficient for inter-decadal studies. The paper acknowledges that agriculture played a role in domestic dissent, but suggests that agrarian reforms likely had a more direct impact on livelihood disruption. The agrarian reforms of 2007-2008 enabled land owners to immediately void tenant contracts and restrict land sales, while those in 2009 terminated fertilizer subsidies. Selby et. al. also brings in the perspective of the Syrian people, who vocalized complaints related to oppression by the Al-Assad regime. Their stated demands were purely anti-authoritarian in nature, with the two core slogans at protests being “the Syrian people will not be humiliated” and “he who kills his own people is a traitor.” Overall, this paper presents a stronger analysis of socio-political factors that contributed to the onset of the war, suggesting that they outweigh contributions of climate change to a drought-induced crisis.

In the event that the lack of water was the main cause of the Syrian conflict, more recent studies, including one from 2019, suggest that geopolitics and water management, rather than climate change-induced drought, would be the primary culprits. The paper “Was Drought Really the Trigger Behind the Syrian Civil War in 2011?” claims that Turkey’s control over the Euphrates upstream from Syria was the primary cause of the latter country’s dearth of water (Karnieli 2019). It opens by explaining that Northern Syria and Southern Turkey have the same climate, semiarid with precipitation ranges between 200 and 350 millimeters per year, despite the presence of a political boundary. The mountains in Eastern Turkey collect precipitation or rely on groundwater to feed into the tributaries that contribute to the majority of the Euphrates’ water. Syria relies heavily on this river, and 60% of the country’s water in total hails from outside of its borders. Turkey and Syria have had two sets of agreements regarding water — one in 1987 to ensure that a fixed amount of water would cross into Syria, and another in 2009 to increase cooperation on water policy. The paper highlights that the flowrate of water across the Turkey-Syria border, recorded at a station near Jarablus, has decreased over the past seventy years. The decreased flow rate is partially associated with changes in climate, but more emphatically correlated with the construction of the Turkish Southeastern Anatolia Project, which consists of 22 dams and 19 hydroelectric power stations.

The study also availed of a metric to assess agricultural productivity in the region: the mean Normalized Difference Vegetation Index. The deviation from the mean could be used to determine whether agricultural production was higher or lower than expected, and the values were obtained from a combined dataset of NOAA-AVHRR and MODIS spaceborne systems. The study reported that up until 2008, both Syria and Turkey saw steady rates of agricultural growth, and in March 2011, there was a sharp deviation in that Turkey saw a dramatic increase in agricultural output while Syria saw a decline. This is notable given that the study emphasized the region around the border, which shares the same climate. The study even analyzed the agricultural output of precipitation-dependent cereals such as wheat. Changes in the vegetation signal, the difference between vegetation states, actually reported a net increase in wheat production in Syria by 13% from five years prior, a phenomenon supported by other studies as well. The increase in precipitation-dependent wheat production suggests that changes in rainfall were not correlated with the overall agricultural output, supporting the theory that Turkey’s control of water upstream from Syria was the main cause of the country’s water destitution. Agricultural productivity had not been examined in the earlier studies, even while it was a key link of the climate-conflict theory. Kelley et. al. (2015) had assumed that a hotter, drier climate would reduce agricultural yields, while Selby et. al. (2017) claimed that agrarian reforms were the main source of a lack of productivity.

While climate change is a real, scientifically-proven phenomenon, its impact on localized conflicts cannot be observed in a vacuum. Climate models have long predicted that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions will wreck irrevocable havoc on Earth’s climate, but in the meantime, natural resource management and related politics may have a greater impact on a population’s access to necessities such as water and land. Unfortunately, over-simplifying the consequences of climate change can misinform the general public and impact policy decisions. This was a concern of Selby et. al. (2017), who wrote that key leaders of the United States of America, such as Former President Barack Obama, current Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry, presidential democratic candidates Martin O’Malley and Bernie Sanders, and Former Vice President and Climate Reality Project founder Al Gore, have all used the Syria case as a core example of climate change impacting regional conflict.

As an example of policy implications, Betsy Hartmann speaks specifically to how the discourse on climate change and conflict can impact the distribution of aid in the regions of interest in her paper “Rethinking Climate Refugees and Climate Conflict: Rhetoric, Reality and the Politics of Policy Discourse” (Hartmann 2010). She notes that statements by Christian Aid, the Center for Naval Analyses, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee, among others, have emphasized a connection between climate change and conflict. Hartmann states that this argument removes the focus of the role of institutions in determining sociopolitical outcomes that involve the environment as an intermediate. Similarly, the paper “Exploring the Climate Change, Migration and Conflict Nexus” by Kate Burrows and Patrick L. Kinney suggests that the environment-migration connection is highly complex, and that resource destitution may actually inhibit migration in some cases (Burrows 2015). The authors note that “conflict” can range from interpersonal to political and that migration may not always be long-term. Nine case studies are reviewed that assert a climate-migration link, but each example only cites one or two key studies. This again speaks to how limits in the amount of data available for individual case studies can make it difficult to draw concrete conclusions.

Climate change itself is well-proven — evidence supporting its societal ramifications is much harder to find. This is especially true in the context of the climate-conflict nexus, as clear sociopolitical indicators for conflict likely mask environmental indicators. While the paper by Kelley, et. al. (2015) was a sound analysis of climate change in the area, its rushed correlation between climate change and the Syrian conflict failed to gauge the magnitude of low precipitation rates as an indicator of civil unrest in comparison to determinants of successful agriculture, resource extraction, regional geopolitics, and political oppression. The simplistic perception of climate change as a “threat magnifier” may mask more powerful determinants contributing to regional conflict. Simultaneously, I will conclude by asking, is there a better way to shed light on the societal ramifications of climate change? Perhaps by the time the consequences are more visible, it will be too late to develop an appropriate response.