An Ambivalent Case for Consumerism as Religious Style

Thrive, cities! Bring your freight, bring your shows, ample and sufficient rivers!

Expand, being than which none else is perhaps more spiritual!

Keep your places, objects than which none else is more lasting!

—Walt Whitman, “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”

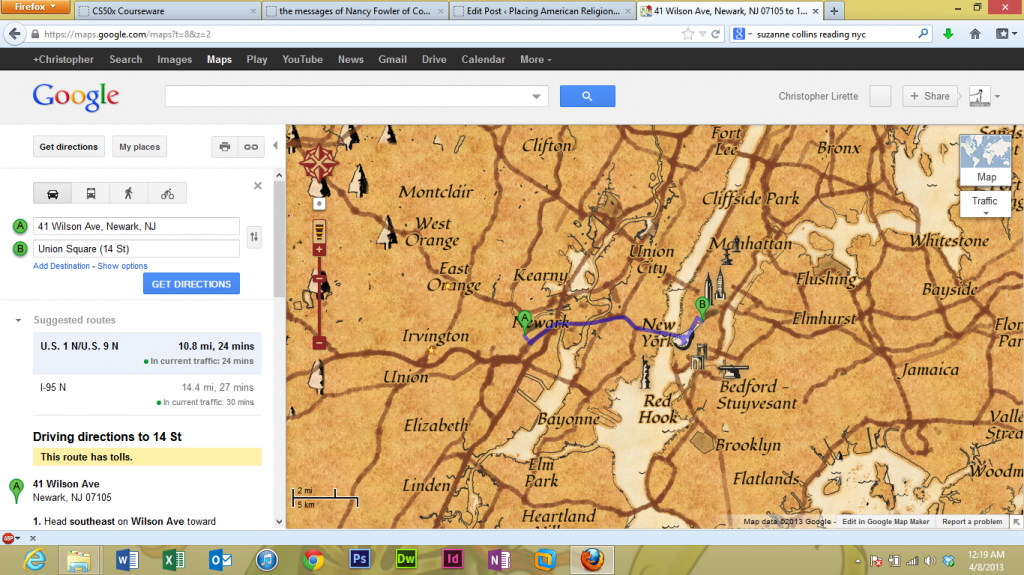

There is a way of conceiving the twenty-first century city as an invading, colonizing god. Although the categories of urban and rural contradicted each other in the popular imagination for at least three hundred years, the categories themselves were internally incoherent: the city representing both progress and regression, plutocracy and indigence, glamor and depravity; its opposite the pure, nostalgic vision of what we wished we were before we had memory, a chthonic place where social connections are strong commitments to community, but also one that is ignorant, silenceable, disconnected. What continued (and continues) to distinguish the urban and the rural from one another is access. When I lived in Newark—which you might not be aware is the same public transit time to Union Square as Carroll Gardens, and twenty minutes faster to NY Penn Station—I had access to the cuisines of every country if not region in Eastern Asia, to readings by writers as diverse as Junot Diaz, Roxane Gay, Billy Collins, and Suzanne Collins, to just about any training possible, to a billion things more than this.

Because I grew up in a town with a mighty 3000+ population and because other cities I’ve lived in include Chicago and Paris, maintaining this access is something very important to me. In Robert Orsi’s introduction to Gods of the City, he reminds people like me that the type of atomized, privileged access to knowledge, culture, and power I desire does not characterize the experience of all city-dwellers. Nevertheless, he also recognizes that the city is not quite as simple as a collection of people who can be divided into privileged/underprivileged, oppressor/oppressed. Rather, people live at the interstices. They believe, but only in negotiation with one thing or another, internalizing and navigating a host of social, historical, personal, cultural, and economic forces that form a palimpsest of imaginary topographies.

So, Orsi’s talking about religion here. That metaphysical concepts become mapped out onto existing grids in the city. That there is no essentialist religious identity that is impermeable and discreet and expresses itself identically regardless of place. I would have to agree with this. But when he defines urban religion (“what comes from the dynamic engagement of religious traditions… with specific features of the industrial and post-industrial cityscapes and with the social conditions of city life” (43)), I wonder if “urban religion” might not be the way one practices religion, the way one believes today.

When a small town, (heterodox) Catholic boy such as myself moves to a city, he has options for faith practice. There’s the Portugeuese parish where the English mass features an extensive homily on why one should bury their parents in a Catholic rather than cremate them. There’s the Italian American parish whose homilies have been translated word for word from the Glen Beck radio hour into Liturgical American English (LAE). There’s a parish run by women priests who were ordained secretly somewhere in the Black Forest by a rogue bishop, where the thirteen parishioners contribute to the homily. There’s also a kung fu school, which features sophisticated training in kicking ass, manipulating qi, fong soi (his sigung is Cantonese), healing practices, and a three-week-long celebration of Chinese New Year with full dragon and lion regalia. There’s also the Thelema lodge on Long Island, the Park51 community center, evangelical Korean teenagers who stop people in the occult section of the Barnes and Noble in Clifton, New Jersey.

This is to say nothing about other religious sites such as Midtown Comics, Madison Square Garden, and the headquarters for HBO.

I may be into some serious syncretism, some chaos magic, but I feel that this is not dissimilar to the way religion is practiced elsewhere, practiced the way one practices a commodity, which is to say to use it, adapt it, even as it conforms one’s will back into the model of late capital, the consumerist, infotextual system we are all part of. Take, for instance, the Catholicism of my hometown. It is disconnected physically from the metropole, right? Well it also is one that performs its expression through the lens of charismatic practices that can trace its genealogy from some church somebody coming into contact with other practices—such as the ones found in some Pentecostal denominations—and remixing them. Even locally, there are places of grace that defy both the force of the romantic sublime and the weight of the old homes of eldritch saints and gods. I remember a local business leader who came to speak at my church when I was twelve or so who told the story of meeting Mary at the shipyard he owned amidst stacks of pipes and whatever industrial stuff. Soon, there was an old man who had a mystical cross in his window. Then, a donut-shop owner organized a trip to Conyers for the “last” apparition of Mary.

People in Chauvin not only take their religion very seriously albeit sentimentally, but they also create it from fragments of imaginary pasts, negotiating official Catholicism with mystical pieties that come as much from Hollywood as they do from feast days. They put crawfish on the St. Joseph’s day altar, pulling in New Orleans, Italian Catholic culture and eliding its genealogy, adapting and transforming it. Their children move away and argue with them on issues of faith and politics having all become cynical with the church and heretical in faith. They, the parents and the children, often negotiate their ethics and beliefs through the television and the Internet. And even as the small town case is often the example used to prove the difference of urban things, now it is increasingly hard to peel back the layers of the religious, political, and cultural maps to find a Chauvin that is not already a part of the city, even as access to luxury goods and training are still a good bit of highway away.

One must contend with the fact that religious practice is not (and never could have been) separate from the world. And worse still, it is marketable and often practical. But for me, one who wants to be hollowed out, to be a body without organs, for to better be absorbed (to better absorb) the big, Lacanian Other who is always incomplete and multitudinous (like me, a little o, singing with the voice of Saint Walt: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then, I contradict myself. I am large. I contain multitudes”), this is a relief, a blessing. Orsi points toward the right place where this happens: the cracks, the moments of contradiction and confrontation between place and ideology, culture and politics, body and body.